Unit 7- Energy Balance and Obesity

7.1 Introduction

On December 26, 2018, 33-year-old Colin O’Brady of Portland, Oregon, became the first person to cross the landmass of Antarctica solo, unassisted, and without any resupply shipments. Others had crossed the continent with the help of a wind sail to propel them over the ice or with resupply drops along the way. However, O’Brady completed the 926-mile trek only on skis, pulling a sled packed with food, fuel, and supplies the entire way.

Speed was critical because he was racing Louis Rudd, a 49-year-old British Army captain. And, of course, he didn’t want to run out of food hundreds of miles from the finish. O’Brady won the race, finishing two days ahead of Rudd.[1]

Figure 7.1. Endurance athlete Colin O’Brady, photographed in March 2016

To prepare for the expedition, O’Brady and his team made careful calculations to estimate his nutrient and caloric needs. He’d be skiing every day for about two months, in below zero temperatures and against the constant wind. O’Brady estimated that he’d burn about 10,000 calories per day on his journey, and knew that if he didn’t pack enough food, he wouldn’t have the strength to complete this epic test of endurance in extreme conditions. [2] O’Brady realized that previous Antarctic explorers had died from starvation.

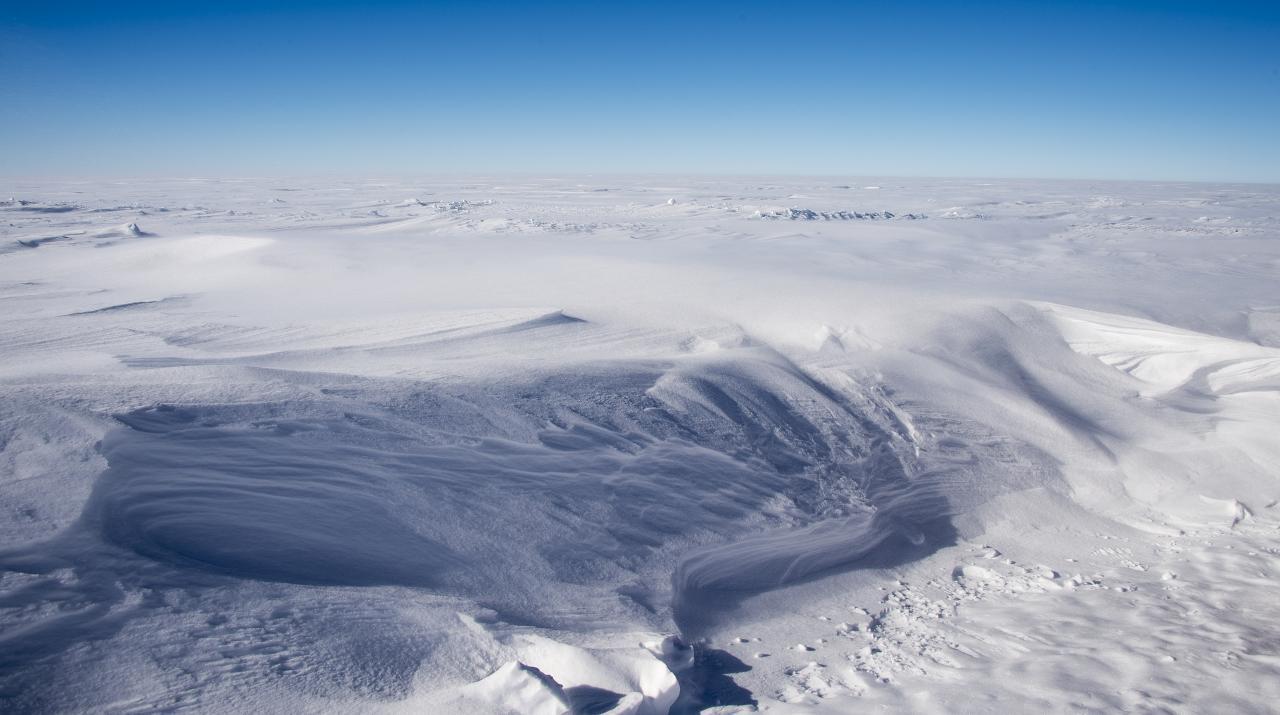

Figure 7.2. O’Brady and Rudd raced across a landscape similar to that shown in this photo from Antarctica—a polar desert and the coldest, windiest, driest continent on earth. It’s land mass is larger than the USA.

O’Brady also realized that the more food he packed, the heavier his sled would be—ironically making him burn more calories, plus slowing him down and prolonging his trip. So he focused on making his food calorie- and nutrient-dense but lightweight: oatmeal with added oil and protein powder; freeze-dried dinners reconstituted with melted snow; and 1,150-calorie bricks of a custom-made “Colin bar” made from coconut oil, nuts, seeds, and dried fruit. He started with 280 of these bricks, enough for four each day.[3]

At the start of his journey, O’Brady’s sled weighed 375 pounds and contained enough food to provide him with 8,000 calories each day. That was a bit short of the 10,000 calories he estimated he’d burn every day, So to build up some additional energy stores, he gained 15 pounds prior to his trip. In the end, after 54 days of skiing through ice and snow, he lost 25 pounds during his Antarctic crossing. He was successful, and while his fitness level and determination surely played a part, the trip would have been impossible without an adequate supply of calories.[4]

We need far fewer calories in our daily lives, than an Antarctic explorer, and we don’t need to carry a two-month supply of food on our backs wherever we go. Thankfully, we get to enjoy fresher and more exciting food options, too. But each of us, whether we’re aware of it or not, is attempting to balance the calories we consume with the calories we burn, just like Colin O’Brady. This is an example of the energy balance concept—one we’ll be exploring throughout this unit.

If you eat roughly the same number of calories as you burn each day, your body weight weight will stay constant. You will lose weight if you burn more calories than you eat like O’Brady did on his expedition. If you overeat, you’ll pack on extra pounds.

Energy balance may seem like a simple concept, but in practice, how many calories you eat versus those used each day is influenced by so many factors that it can be challenging to apply. Still, it’s an important concept to understand. We live in a world where food is readily available, and we’re bombarded with marketing messages telling us to eat more. Not surprisingly, the prevalence of obesity is rising around the globe, and the health effects of carrying too much weight are a concern. On the other hand, being underweight or overly focused on body weight also carries health risks. In this unit, we’ll explore these problems and seek some answers.

Unit Learning Objectives

After completing this unit, you will be able to:

- Understand the concepts of energy input and expenditure, energy balance, and how they relate to body weight.

- Describe the concerns with being underweight and overweight, appreciating that body weight affects a person’s physical health but also their mental health and their experience living in a world with unrealistic expectations around body size and shape.

- Describe the characteristics of a healthy body composition, ways that it can be measured, and limitations to these measurements.

- Recognize the global trends in the rising rates of obesity worldwide, and identify possible causes and solutions among children and adults.

- Understand the challenge of and best practices for managing body weight in a way conducive to physical and mental health.

- Acknowledge the importance of a moderate approach when it comes to nutrition and weight management.

- Recognize that nutrition and its effect on our physical body is only one dimension of health and others are equally important.

Attributions

- Lane Community College’s Nutrition: Science and Everyday Application ” Energy Balance” CC BY-NC 4.0

- Skolnick A. Racing across Antarctica, one freezing day at a time. November 29, 2018. The New York Times. Accessed January 17, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/29/sports/antarctica-ski-race.html[ ↵

- Neville T. Colin O’Brady wants to tell you a story. Outside Online website. August 15, 2019. Accessed January 17, 2022, https://www.outsideonline.com/2400795/colin-obrady-profile-antarctica ↵

- Hutchinson A. How to fuel a solo, unassisted Antarctic crossing. Outside Online website. November 14, 2018. Accessed January 17, 2022, https://www.outsideonline.com/2365661/colin-obrady-how-fuel-solo-unassisted-antarctic-crossing ↵

- Neville T. Colin O’Brady wants to tell you a story. Outside Online website. August 15, 2019. Accessed January 17, 2022, https://www.outsideonline.com/2400795/colin-obrady-profile-antarctica ↵

The unit used to measure the energy in food.

The average person needs about 2000 to 2500 calories.

Maintaining calories (energy) consumed with the calories expended. Consuming more calories that expended results in weight gain. Expending more calories than consumed results in weight loss.

WHO considers it as an "abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health." Having a BMI over 30. Most people weigh 50 pounds or more than is desirable.

A body weight that is too low to maintain health.