Unit 9 – Vitamins and Minerals Part 2

9.6 Vitamins and Minerals Involved in Blood Health

Blood is essential to life. It transports absorbed nutrients and oxygen to cells, removes metabolic waste products for excretion, and carries molecules, such as hormones, to allow for communication between organs.

Blood is a connective tissue of the circulatory system, made up of four components forming a matrix:

- red blood cells (or erythrocytes), which transport oxygen to cells

- white blood cells (or leukocytes), which are part of the immune system and help destroy foreign invaders

- platelets, which are fragments of cells that circulate to assist in blood clotting

- plasma, which is the fluid portion of the blood and contains proteins that help transport nutrients (e.g., fat-soluble vitamins) and aid in blood clotting.

Maintaining healthy blood, including its continuous renewal, is essential to support its vital functions. Blood health is acutely sensitive to deficiencies in some vitamins and minerals, especially iron and vitamin K.

Iron

Iron is a trace mineral. It is a necessary component of many proteins in the body responsible for functions such as the transport of oxygen, energy metabolism, and immune function. Iron is also important in brain development and function.

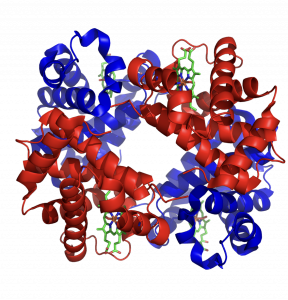

Iron is essential for oxygen transport because of its role in hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells that transports oxygen to cells and gives red blood cells their color as illustrated in Figure 9.12.

Figure 9.12. The structure of hemoglobin and the heme complex. On the left, the structure of hemoglobin includes four globular proteins (shown in blue and red) and the iron-containing heme groups (shown in green). On the right is a closer view of the heme complex.

The iron in hemoglobin is what binds to oxygen, allowing for transportation to cells. If iron levels are low, hemoglobin is not synthesized in sufficient amounts, and the oxygen-carrying capacity of red blood cells is reduced, resulting in anemia. Iron is also an important part of myoglobin, a protein similar to hemoglobin but found in muscles.

Dietary Sources of Iron

There are two types of iron found in foods: heme iron and non-heme iron.

- Heme iron is iron that is part of the proteins hemoglobin and myoglobin, so it is found only in foods of animal origin, such as meat, poultry, and fish. Heme iron is the most bioavailable form of iron.

- Non-heme iron is a mineral by itself and is not a part of hemoglobin or myoglobin. Non-heme iron can be found in foods from both plants (e.g., nuts, beans, vegetables, and fortified and whole grains) and animals. It is less bioavailable than heme iron. Consuming vitamin C, meat, poultry, and seafood with non-heme iron increases its bioavailability. For example, eating an orange ( a good source of vitamin C) along with your bowl of vegetarian chili will help you to absorb more of the iron from the beans and vegetables.1

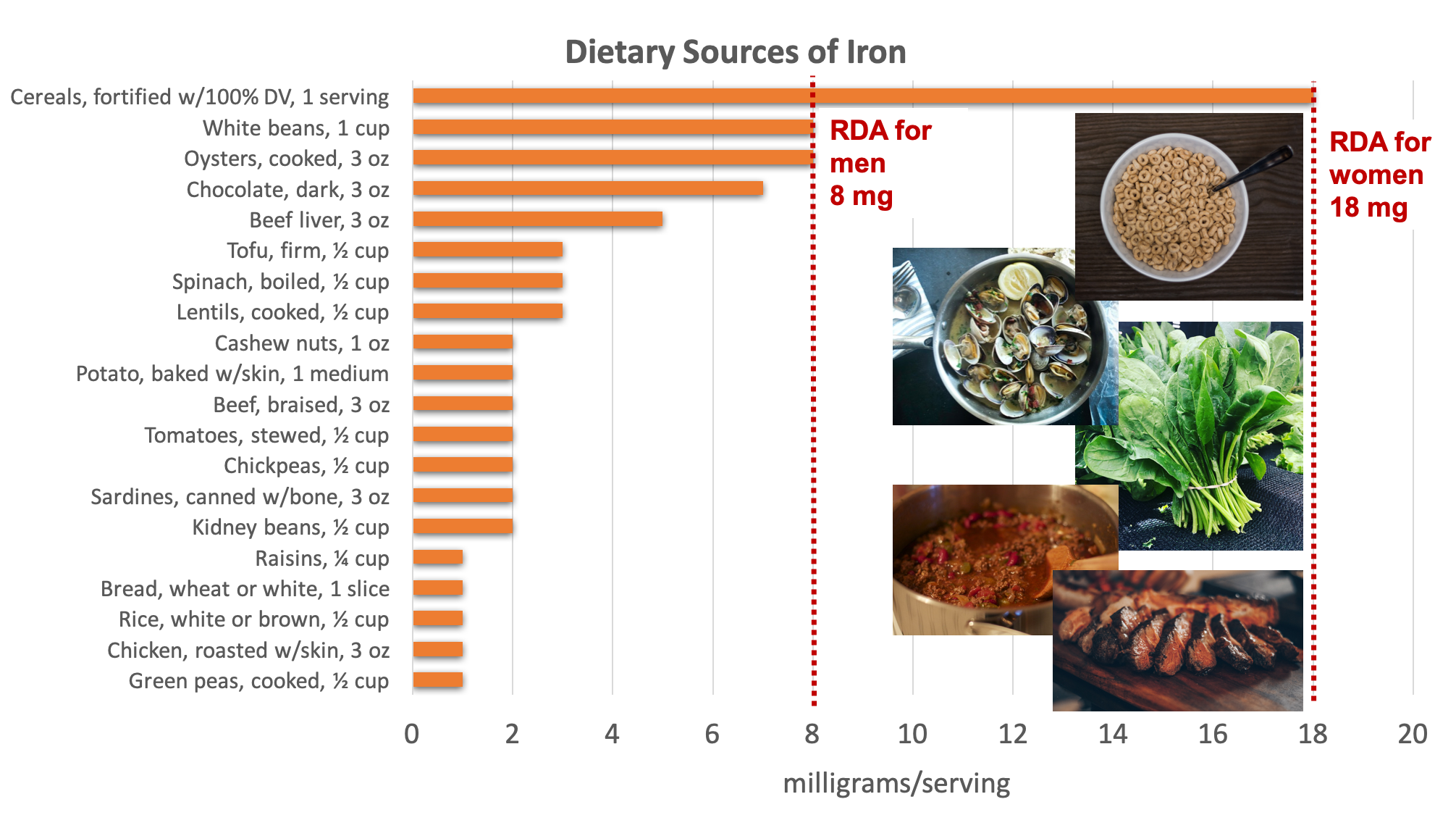

Figure 9.13. Dietary sources of iron. Examples of good sources pictured include fortified cereal, clams, spinach, lentils and red meat. Source: NIH Office of Dietary Supplements

The bioavailability of iron is approximately 14% to 18% from mixed diets and 5% to 12% from vegetarian diets.2 Bioavailability is influenced by the dietary factors previously mentioned, as well as iron status. The body has no physiological mechanism to excrete iron; therefore, iron balance is tightly regulated by absorption.2 When iron stores are low, more dietary iron will be absorbed.

The majority of the body’s iron needs are not met by dietary sources, but rather by recycling iron within the body (endogenous sources). Ninety percent of daily iron needs are met by recycling iron released from the breakdown of aging cells, mostly red blood cells.2

Iron Deficiency and Toxicity

Iron deficiency is one of the most common nutrient deficiencies, affecting more than a third of the world’s population.3 Iron-deficiency anemia is a condition that develops from insufficient iron levels in the body, resulting in fewer and smaller red blood cells that contain less hemoglobin. As a result, blood carries less oxygen from the lungs to cells. Iron-deficiency anemia has the following signs and symptoms, which are linked to the essential functions of iron in energy metabolism and blood health:

- Fatigue

- Weakness

- Pale skin

- Shortness of breath

- Dizziness

- Swollen, sore tongue

- Abnormal heart rate

Infants, children, adolescents, and women are most at risk worldwide for iron-deficiency anemia.4 Infants who are premature, have low birth weight, or have a mother with iron deficiency are at risk for iron deficiency, because they are born with low iron stores relative to the amount needed for growth and development. Young children and adolescent girls are at risk for iron deficiency due to rapid growth, low dietary intake of iron, as well as heavy menstruation for adolescent girls. In these populations, iron-deficiency anemia can also cause the following signs and symptoms: pica (an intense craving for and ingestion of non-food items such as paper, dirt, or clay), poor growth, failure to thrive, and poor performance in school, as well as mental, motor, and behavioral disorders. Women who experience heavy menstrual bleeding, or who are pregnant, are also at risk for iron inadequacy due to their increased requirements for iron.

To give you a better understanding of these risks, it is helpful to look at how much higher the RDA is for women of reproductive age and pregnant women compared to men (Table 9.2).1 To put this in perspective, 3 ounces of beef contains about 3 milligrams of iron, making it challenging for some women to meet their daily iron requirement.

|

Population Group |

RDA for Iron |

|

Women of reproductive age, 19-50 years |

18 mg/day |

|

Pregnancy, 19- 50 years |

27 mg/day |

|

Men, 19-50 years |

8 mg/day |

Table 9.2. A comparison of the RDAs for adult women of reproductive age, pregnancy, and adult men.

Healthy adults are at little risk of iron overload from foods, but too much iron from supplements can result in gastric upset, constipation, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.1 The body excretes little iron; therefore, the potential for toxicity from supplements is a concern.1

Folate

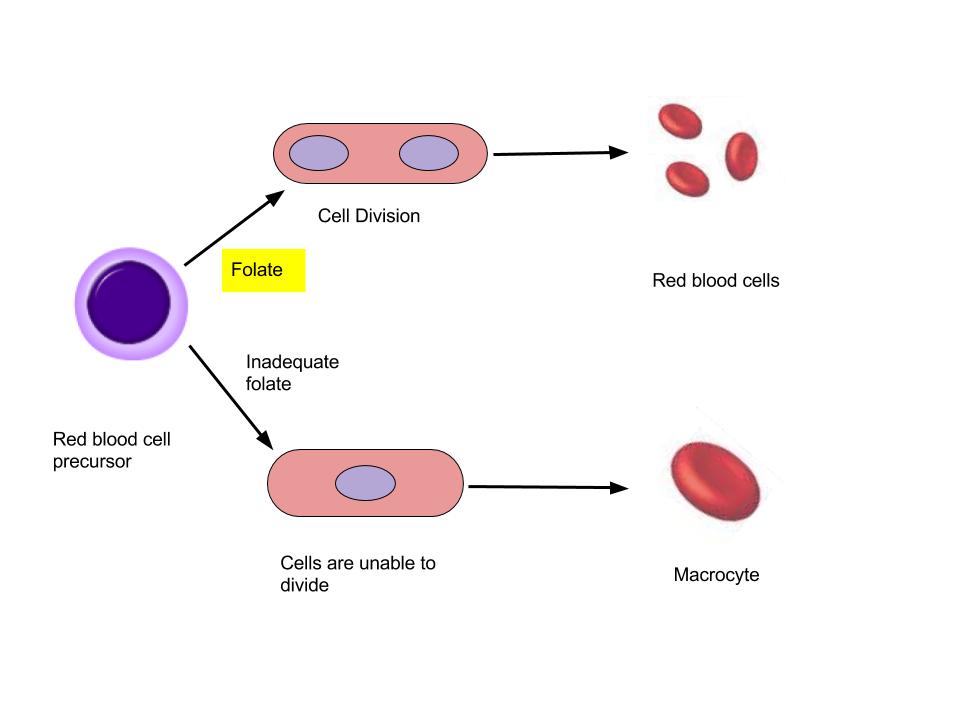

Folate, or vitamin B9, is involved in cell division. Our bodies are continuously synthesizing red blood cells in the bone marrow. When folate is deficient, cells do not divide normally, resulting in large red blood cells, a condition known as macrocytic anemia. Macrocytic means “big cell,” and anemia refers to fewer red blood cells or hemoglobin. Therefore, macrocytic anemia is characterized by larger and fewer red blood cells that are less efficient at carrying oxygen.

Figure 9.14. Folate and the formation of macrocytic anemia.

Folate is especially essential for the growth and specialization of cells of the central nervous system.

Dietary Sources of Folate

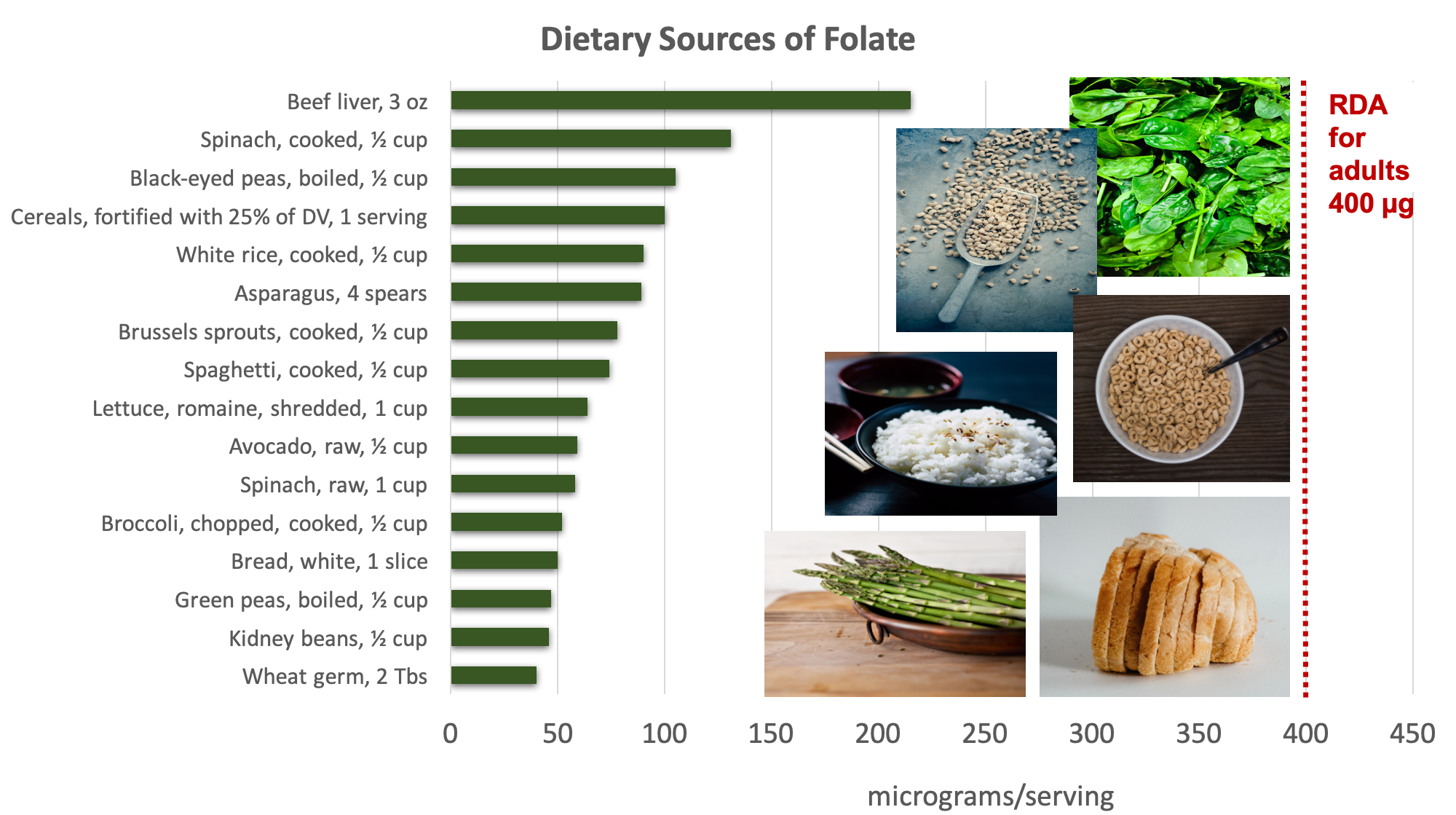

Folate is found naturally in a wide variety of foods, including vegetables (particularly dark leafy greens), fruits, nuts, beans, legumes, meat, poultry, eggs, and grains. As mentioned, folic acid (the synthetic folate) is also found in enriched foods such as grains.

Figure 9.15. Dietary sources of folate. Examples of good sources pictured include spinach, black-eyed peas, fortified cereal, rice, and bread and asparagus. Source: NIH Office of Dietary Supplements

Folate Deficiency and Toxicity

Folate deficiency is typically due to an inadequate dietary intake; however, smoking and heavy, chronic alcohol intake can also decrease absorption, leading to a folate deficiency.2 The primary sign of a folate deficiency is macrocytic anemia, characterized by large, abnormal red blood cells, which can lead to symptoms of fatigue, weakness, poor concentration, headache, irritability, and shortness of breath. Other symptoms of folate deficiency can include mouth sores, gastrointestinal distress, and changes in the skin, hair, and nails. Women with insufficient folate intakes are at increased risk of giving birth to infants with neural tube defects and low intake during pregnancy has been associated with preterm delivery, low birth weight, and fetal growth retardation.3

Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin)

Vitamin B12 is a unique vitamin because it contains an element (cobalt) and is found almost exclusively in animal products. Neither plants nor animals can synthesize vitamin B12; only bacteria can synthesize it. The vitamin B12 found in animal-derived foods was produced by microorganisms within the animals. Animals consume the microorganisms in soil, or microorganisms in the GI tract of animals produce vitamin B12 that can then be absorbed.

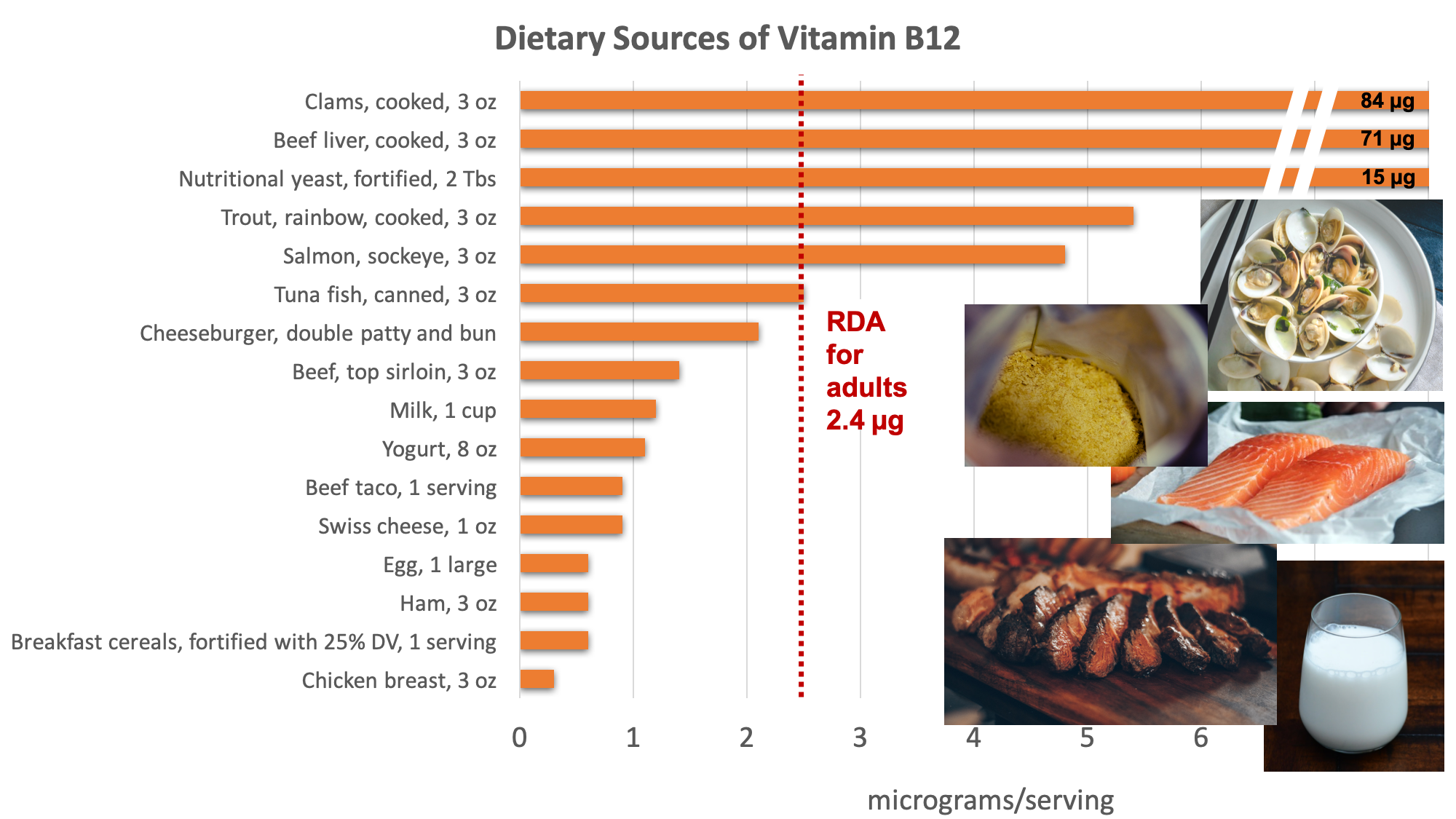

Dietary Sources of Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is found naturally in animal products such as fish, meat, poultry, eggs, and milk products. Although vitamin B12 is not generally present in plant foods, fortified breakfast cereals are also a good source of vitamin B12. Because vitamin B12 is only found primarily in animal products, it is important for strict vegetarians who consume no animal products (vegans) to get vitamin B12 either through supplements, nutritional yeast, or fortified products like cereals and soy milk. Recent research suggests some plant-based sources like edible algae, mushrooms, and fermented vegetables may contain substantial amounts of vitamin B12 as well.2

Figure 9.16. Dietary sources of vitamin B12. Examples of good sources pictured include clams, salmon, nutritional yeast, red meat, and milk. Source: NIH Office of Dietary Supplements, www.bragg.com

Vitamin B12 Deficiency and Toxicity

When there is a deficiency in vitamin B12, inactive folate (from food) is unable to be converted to active folate and used in the body for the synthesis of DNA. However, folic acid from supplements or fortified foods is available to be used as active folate in the body without vitamin B12. Therefore, if there is a deficiency in vitamin B12, macrocytic anemia may occur. Vitamin B12 deficiency also results in nerve degeneration and abnormalities that can often precede the development of anemia. These include a decline in mental function and burning, tingling, and numbness of the legs. These symptoms can continue to worsen, and deficiency can be fatal.4

Because vitamin B12 is found primarily in foods of animal origin, a strict vegetarian diet can result in cases of vitamin B12 deficiency. Therefore, careful dietary planning to include fortified sources or supplements of vitamin B12 is important to prevent deficiency in a vegan diet.

No toxicity of vitamin B12 has been reported. Because of the low risk for toxicity, a tolerable upper intake level (UL) has not been established for vitamin B12.4

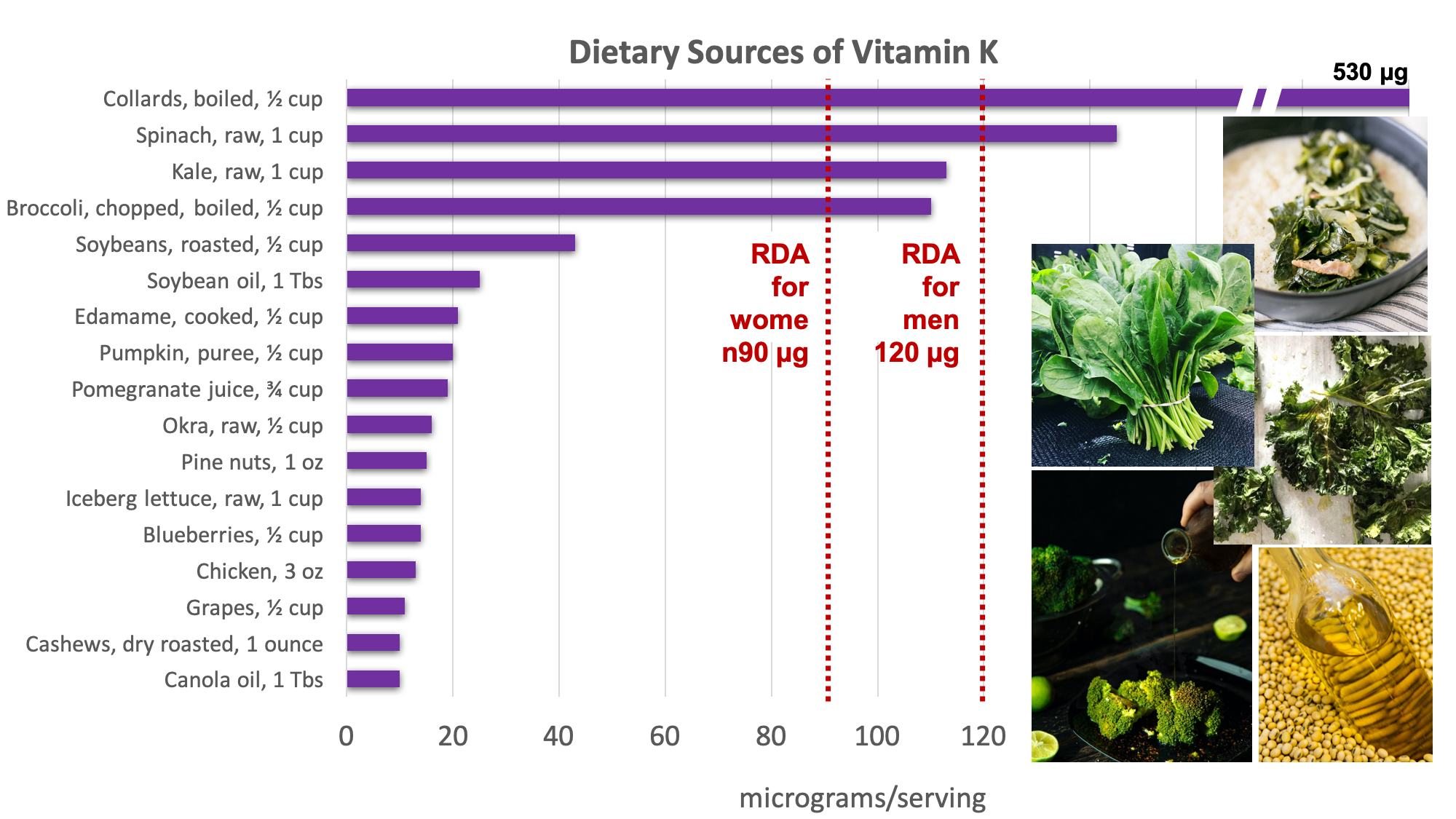

Vitamin K

Vitamin K refers to a group of fat-soluble vitamins that are similar in chemical structure. They act as coenzymes and have long been known to play an essential role in blood coagulation or clotting. Vitamin K is also required for maintaining bone health, as it modifies a protein that is involved in the bone remodeling process.

Dietary Sources of Vitamin K

Vitamin K is found in the highest concentrations in green vegetables such as collard and turnip greens, kale, broccoli, and spinach. Soybean and canola oil are also common sources of vitamin K in the U.S. diet.5 Additionally, vitamin K can be synthesized by bacteria in the large intestine, but the bioavailability of bacterial vitamin K is unclear.

Figure 9.17. Dietary sources of vitamin K. Examples of good sources pictured include chard, spinach, kale, broccoli, and soybean oil. Source: NIH Office of Dietary Supplements

Self-Check:

Attributions:

- Lane Community College’s Nutrition: Science and Everyday Application CC BY-NC.4.0

Resources:

- 1National Institutes of Health of Dietary Supplements. Iron – Health Professional Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 29, 2020 from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Iron-HealthProfessional/

- 2Richard Hurrell, Ines Egli, Iron bioavailability and dietary reference values, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 91, Issue 5, May 2010, Pages 1461S–1467S, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.28674F

- 3Chaparro, C. M., & Suchdev, P. S. (2019). Anemia epidemiology, pathophysiology, and etiology in low- and middle-income countries. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1450(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14092

- 4Powers JM, Buchanan GR. (2019). Disorders of iron metabolism: New diagnostic and treatment approaches to iron deficiency. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am, 33(3):393-408, doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2019.01.006

- 5National Institutes of Health of Dietary Supplements. Vitamin K – Health Professional Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 29, 2020 from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminK-HealthProfessional/

Images:

- Figure 9.12. “Structure of Hemoglobin” by Zephyris at English Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 and “Heme” by Yikrazuul is in the Public Domain

- Table 9.2. “A comparison of the RDAs” by Tamberly Powell is licensed under CC BY 4.0 with data from National Institutes of Health of Dietary Supplements. Iron – Health Professional Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 29, 2020 from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Iron-HealthProfessional/#en4

- Figure 9.13. “Dietary sources of iron” by Alice Callahan is licensed under CC BY 4.0, with images: Breakfast cereal by John Matychuk, clams by Adrien Sala, spinach by Elianna Friedman, steak by Emerson Vieira on Unsplash (license information); “Superbowl Chili” by Jake Przespo is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

- Figure 9.17. “Dietary sources of vitamin K” by Alice Callahan is licensed under CC BY 4.0, with images: Collards by Kim Daniels, spinach by Elianna Friedman, kale by Ronit Shaked, broccoli by Hessam Hojati, all on Unsplash (license information); “High oleic acid soybean oil_0030” by Mizzou CAFNR is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0