Unit 11 — Lifespan Nutrition

11.7 Nutrition for Older Adults

Although there is no one particular age used to define “older adult,” the RDA includes a category for ages 51 to 70 and another category age 71 and up. A number of physiological and emotional changes take place during this life stage, and as they age, older adults can face a variety of health challenges. Blood pressure rises, and the immune system may have more difficulty battling invaders and infections. The skin becomes thinner and more wrinkled and may take longer to heal after injury. Older adults may gradually lose an inch or two in height. And short-term memory might not be as keen as it once was. However, many older adults remain in relatively good health and continue to be active into their golden years. Good nutrition is important to maintaining health later in life. In addition, the fitness and nutritional choices made earlier in life set the stage for continued health and happiness.

Nutrient Needs in Older Adults

As noted in Unit 1, Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) vary based on age. Beginning at age 51, nutrient requirements for adults change in order to fit the nutritional issues and health challenges that older people face, and change again at age 70. Because the process of aging affects nutrient needs, some requirements for nutrients decrease as a person ages, while requirements for other nutrients increase. On this page, we will take a look at the changing nutrient requirements for older adults as well as some special concerns for the aging population.

Energy and Macronutrients

Due to reductions in lean body mass and metabolic rate, older adults have lower calorie needs than younger adults. The energy requirements for people ages 51 and older are 1,600 to 2,200 calories for women and 2,000 to 2,800 calories for men, depending on activity level. The decrease in physical activity that is typical of older adults also influences nutrition requirements. The AMDRs for carbohydrates, protein, and fat remain the same from middle age into old age. Older adults should substitute more unrefined carbohydrates, such as whole grains, for refined ones. Fiber is especially important in preventing constipation and diverticulitis, which is more common as people age, and it may also reduce the risk of colon cancer. Protein should be lean, and healthy fats, such as omega-3 fatty acids, are a part of any good diet.

Micronutrients

The recommended intake levels of several micronutrients are increased in older adulthood, while others are decreased. A few nutrient changes to note include the following:

- To slow bone loss, the recommendations for calcium increase from 1,000 milligrams per day to 1,200 milligrams per day for women at age 51 and for men at age 70.

- Also to help protect bones, vitamin D recommendations increase from 600 IU to 800 IU per day for men and women at age 70.

- Vitamin B6 recommendations rise to 1.7 milligrams per day for older men and 1.5 milligrams per day for older women to help lower levels of homocysteine and protect against cardiovascular disease.

- Due to a decrease in the production of stomach acid, which can lead to an overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine and decrease absorption of vitamin B12, older adults need an additional 2.4 micrograms per day of B12 compared to younger adults.

- For elderly women, higher iron levels are no longer needed post-menopause, and recommendations decrease from 18 milligrams per day to 8 milligrams per day at age 51.

Common Health Concerns in Older Adults

Older adults may face serious health challenges in their later years, many of which have ties to nutrition.

- Increased occurrence of cancer, heart disease, and diabetes

- Loss of hormone production, bone density, muscle mass, and strength, as well as changes in body composition (increase of fat deposits in the abdominal area, increasing the risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease)

- Increased occurrence of dementia, resulting in memory loss, agitation and delusions

- Decreased kidney function, becoming less effective in excreting metabolic products such as sodium, acid, and potassium, which can alter water balance and hydration status

- Decreased immune function, resulting in more susceptibility to illness

- Increased risk for neurological disorders and psychological conditions (e.g., depression), influencing attitudes toward food, along with the ability to prepare or ingest food

- Dental problems can lead to difficulties with chewing and swallowing, which in turn can make it hard to maintain a healthy diet

- Lower efficiency in the absorption of vitamins and minerals

- Being either underweight or overweight

Nutrition Concerns for Older Adults

Dietary choices can help improve health during this life stage and address some of the nutritional concerns that many older adults face. In addition, there are specific concerns related to nutrition that affect adults in their later years. They include medical problems, such as disability and disease, which can impact diet and activity level.

Sensory Issues

At about age 60, taste buds begin to decrease in size and number. As a result, the taste threshold is higher in older adults, meaning that more of the same flavor must be present to detect the taste. Many elderly people lose the ability to distinguish between salty, sour, sweet, and bitter flavors. This can make food seem less appealing and decrease appetite. Intake of foods high in sugar and sodium can increase due to an inability to discern those tastes. The sense of smell also decreases, which impacts attitudes toward food. Sensory issues may also affect digestion, because the taste and smell of food stimulates the secretion of digestive enzymes in the mouth, stomach, and pancreas.

Many older people suffer from vision loss and other vision problems. Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of blindness in Americans over age sixty.2 This disorder can make food planning and preparation extremely difficult, and people who suffer from it often depend on caregivers for their meals. Self-feeding also may be difficult if an elderly person cannot see their food clearly. Friends and family members can help older adults with shopping and cooking. Food-assistance programs for older adults (such as Meals on Wheels) can also be helpful. Diet may also help to prevent macular degeneration. Consuming colorful fruits and vegetables increases the intake of lutein and zeaxanthin, two antioxidants that provide protection for the eyes.

Dysphagia

Some older adults have difficulty getting adequate nutrition because of the disorder dysphagia, which impairs the ability to swallow. Stroke, which can damage the parts of the brain that control swallowing, is a common cause of dysphagia. Dysphagia is also associated with advanced dementia because of overall brain function impairment. To assist older adults suffering from dysphagia, it can be helpful to alter food consistency. For example, solid foods can be pureed, ground, or chopped to allow more successful and safe swallowing. This decreases the risk of aspiration, which occurs when food flows into the respiratory tract and can result in pneumonia. Typically, speech therapists, physicians, and dietitians work together to determine the appropriate diet for dysphagia patients.

Obesity in Old Age

Similar to other life stages, obesity is a concern for the elderly. Adults over age 60 are more likely to be obese than young or middle-aged adults. Reduced muscle mass and physical activity mean that older adults need fewer calories per day to maintain a normal weight. Being overweight or obese increases the risk for potentially fatal conditions that can afflict older adults, particularly cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Obesity is also a contributing factor for a number of other conditions, including arthritis.

For older adults who are overweight or obese, dietary changes to promote weight loss should be combined with an exercise program to protect muscle mass. This is because dieting reduces muscle as well as fat, which can exacerbate the loss of muscle mass due to aging. Although weight loss among the elderly can be beneficial, it is best to be cautious and consult with a healthcare professional before beginning a weight loss program.

Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia is the age-related decrease in muscle mass and strength that occurs in 10 to 20 percent of older adults. Muscle mass begins to decline as early as 30 years but is more prevalent in those age 60 and above, with the condition worsened with advancing age. Symptoms of sarcopenia include:

- Frequent falls and bone fractures

- Muscle weakness

- Slow walking speed

- Difficulty with shopping and cooking

Fortunately, severe sarcopenia may be prevented with adequate nutrition, especially ample protein intake, and weight bearing exercise.

Some older adults are diagnosed sarcopenic obesity, which might sound the a contradiction. However the condition is being recognized more in the medical community more frequently today.

The Anorexia of Aging

In addition to concerns about obesity among senior citizens, being underweight can be a major problem. A condition known as the anorexia of aging is characterized by poor food intake, which results in dangerous weight loss. This major health problem among the elderly leads to a higher risk for immune deficiency, frequent falls, muscle loss, and cognitive deficits. It is important for health care providers to examine the causes for anorexia of aging, which can vary from one individual to another. Understanding why some elderly people eat less as they age can help healthcare professionals assess the risk factors associated with this condition. Decreased intake may be due to disability or the lack of a motivation to eat. Also, many older adults skip at least one meal each day. As a result, some elderly people are unable to meet even reduced energy needs.

Nutrition interventions for anorexia of aging should focus primarily on a healthy diet. Remedies can include increasing the frequency and variety of meals and adding healthy, high-calorie foods (such as nuts, potatoes, whole-grain pasta, and avocados) to the diet. The use of flavor enhancements with meals and oral nutrition supplements between meals may help to improve caloric intake.1 Health care professionals should consider a patient’s habits and preferences when developing a nutrition treatment plan. After a plan is in place, patients should be weighed on a weekly basis until they show improvement.

Longevity and Nutrition

Bad habits and poor nutrition have an accrual effect. The foods you consume in your younger years will impact your health as you age, from childhood into the later stages of life. As a result, good nutrition today means optimal health tomorrow. Therefore, it is best to start making healthy choices from a young age and maintain them as you mature. However, research suggests that adopting good nutritional choices later in life, during the 40s, 50s, and even the 60s, may still help to reduce the risk of chronic disease as you grow older.3

Even if past nutrition and lifestyle choices were not aligned with dietary guidelines, older adults can still do a great deal to reduce their risk of disability and chronic disease. There are a number of changes middle-aged adults can implement, even after years of unhealthy choices. Choices include eating more dark, green, leafy vegetables, choosing lean sources of protein such as lean meats, poultry, fish, beans, and nuts, and engaging in moderate physical activity for at least thirty minutes per day, several days per week. The resulting improvements will go a long way toward providing greater protection against falls and fractures, and helping to ward off cardiovascular disease and hypertension, among other chronic conditions.3

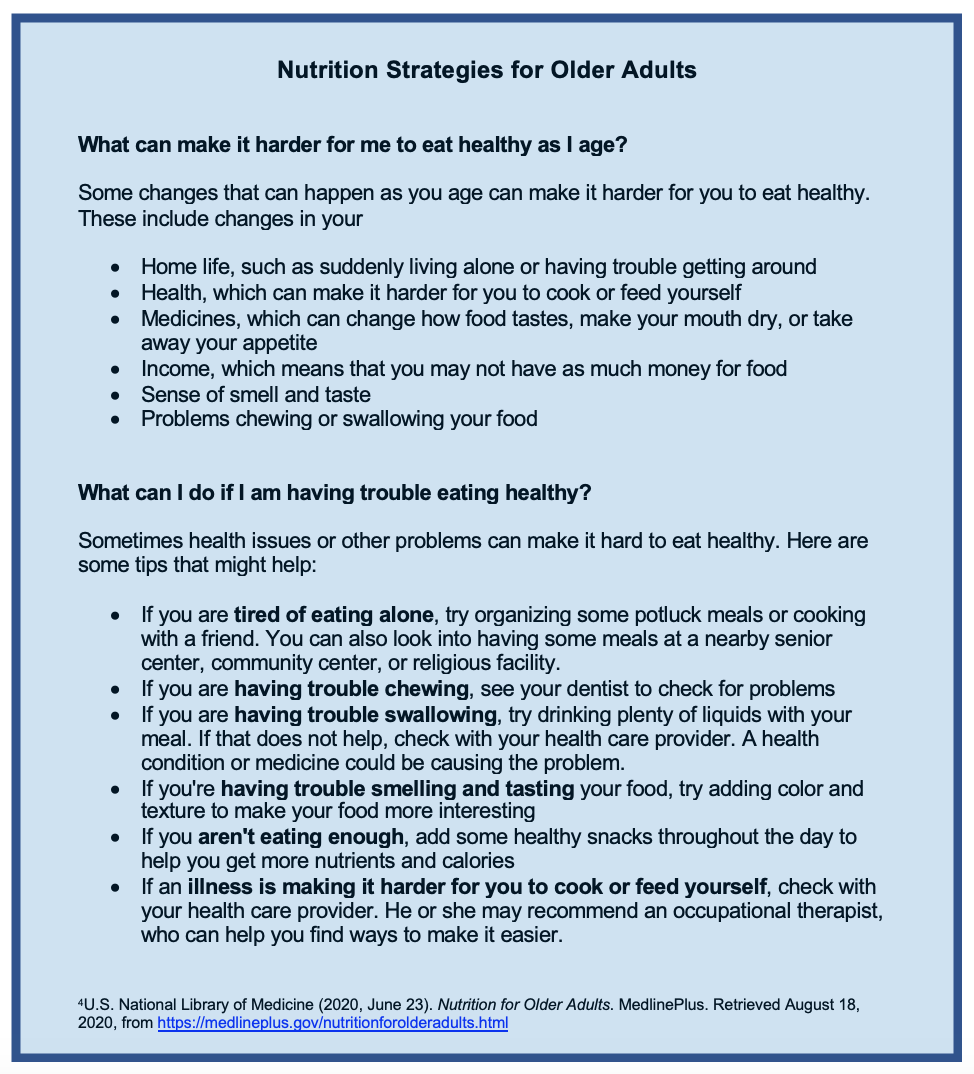

Figure 11.8. Nutrition strategies for older adults

Review Questions

Attributions:

- Lane Community College’s Nutrition: Science and Everyday Application. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/nutritionscience/ ” CC BY-NC 4.0

References:

- 1Cox, N. J., Ibrahim, K., Sayer, A. A., Robinson, S. M., & Roberts, H. C. (2019). Assessment and treatment of the anorexia of aging: A systematic review. Nutrients, 11(1), 144. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6356473/

- 2Ehrlich, R., Harris, A., Kheradiya, N. S., Winston, D. M., Ciulla, T. A., & Wirostko, B. (2008). Age-related macular degeneration and the aging eye. Clinical interventions in aging, 3(3), 473.

- 3Rivlin, R. S. (2007). Keeping the young-elderly healthy: Is it too late to improve our health through nutrition? The American journal of clinical nutrition, 86(5), 1572S-1576S.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine (2020, June 23). Nutrition for Older Adults. MedlinePlus. Retrieved August 18, 2020, from https://medlineplus.gov/nutritionforolderadults.html

Image Credits:

- Photo of man kissing woman by Esther Ann on Unsplash (license information)

- Photo of older woman cooking by CDC on Unsplash (license information)

- Figure 11.8. “Nutrition Strategies for Older Adults” by Heather Leonard is licensed under CC BY 4.0