Developing the Persuasive Speech: Appealing to an Audience

Persuasion only occurs with an audience, so your main goal is to answer the question, “how do I persuade the audience to believe my proposition of fact, value, or policy?”

To accomplish this goal, identify your target audience—individuals who are willing to listen to your argument despite disagreeing, having limited knowledge, or lacking experience with your advocacy. Because persuasion involves change, you are targeting individuals who have not yet changed their beliefs in favor of your argument.

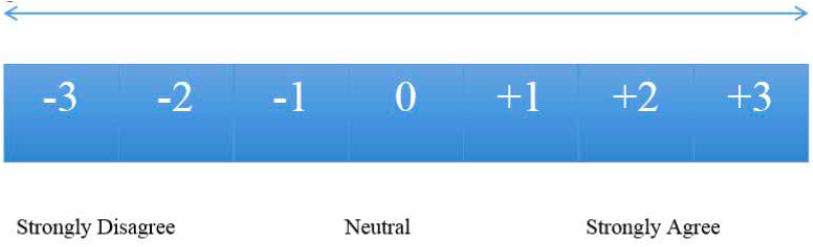

The persuasive continuum (Figure 17.1) is a tool that allows you to visualize your audience’s relationship with your topic.

Figure 17.1

The persuasive continuum views persuasion as a line going both directions. Your audience members, either as a group or individually, are sitting somewhere on that line in reference to your thesis statement, claim, or proposition.

For example, your proposition might be, “The main cause of climate change is human activity.” In this case, you are not denying that natural forces, such as volcanoes, can affect the climate, but you are claiming that human pollution is the central force behind global warming. To be an effective persuasive speaker, one of your first jobs is determining where your audience “sits” on the continuum.

+3 means strongly agree to the point of making lifestyle choices to lessen climate change (such as riding a bike instead of driving a car, recycling, eating certain kinds of foods).

+2 means agree but not to the point of acting upon it.

+1 as mildly in favor of your proposition; that is, they think it’s probably true, but the issue doesn’t affect them personally.

0 means neutral, no opinion, or feeling uninformed enough to make a decision.

-1 means mildly opposed to the proposition but willing to listen to those with whom they disagree.

-2 means disagreement to the point of dismissing the idea pretty quickly.

-3 means strong opposition to the point that the concept of climate change itself is not even listened to or acknowledged as a valid subject.

Since everyone in the audience is somewhere on this line or continuum, persuasion means moving them to the right, somewhere closer to +3.

Your topic will inform which strategy you use to move your audience along the continuum. If you are introducing an argument that the audience lacks knowledge in, you are moving an audience from 0 to +1, +2, or +3. The audience’s attitude will be a 0 because they have no former opinion or experience.

Thinking about persuasion as a continuum has three benefits:

- You can visualize and quantify where your audience lands on the continuum

- You can accept the fact that any movement toward +3 or to the right is a win.

- You can see that trying to change an audience from -3 to +3 in one speech is just about impossible. Therefore, you will need to take a reasonable approach. In this case, if you knew most of the audience was at -2 or -3, your speech would be about the science behind climate change in order to open their minds to its possible existence. However, that audience is not ready to hear about its being caused mainly by humans or what action should be taken to reverse it.

As you identify where your target audience sits on the continuum, you can dig deeper to determine what values, attitude, or beliefs would prohibit individuals from supporting the proposition or values, attitudes, or beliefs that support your proposition. At the same time, avoid language that assumes stereotypical beliefs about the audience.

For example, your audience may value higher education and believe that education is useful for critical thinking skills. Alternatively, you may have an audience that values work experience and believes that college is frivolous and expensive. Being aware of these differing values will deepen your persuasive content by informing what evidence or insights to draw on and upon for each audience type.

Once you’re confident about where your audience is on the continuum and what values they hold, you can select the appropriate rhetorical appeals – ethos, pathos, and logos—to motivate your audience toward action. Yes, we’ve discussed these rhetorical appeals before, but they are particularly useful in persuasive speaking, so let’s review again.

Persuasive Strategies

Ethos

“Danny Shine Speaker’s Corner” by Acapeloahddub. Public domain.

In addition to understanding how your audience feels about the topic you are addressing, you will need to take steps to help them see you as credible and interesting. The audience’s perception of you as a speaker is influential in determining whether or not they will choose to accept your proposition. Aristotle called this element of the speech ethos, “a Greek word that is closely related to our terms ethical and ethnic.”[1] He taught speakers to establish credibility with the audience by appearing to have good moral character, common sense, and concern for the audience’s well-being.[2] Campbell & Huxman explain that ethos is not about conveying that you, as an individual, are a good person. It is about “mirror[ing] the characteristics idealized by [the] culture or group” (ethnic),[3] and demonstrating that you make good moral choices with regard to your relationship within the group (ethics).

While there are many things speakers can do to build their ethos throughout the speech, “assessments of ethos often reflect superficial first impressions,” and these first impressions linger long after the speech has concluded.[4] This means that what you wear and how you behave, even before opening your mouth, can go far in shaping your ethos. Be sure to dress appropriately for the occasion and setting in which you speak. Also work to appear confident, but not arrogant, and be sure to maintain enthusiasm about your topic throughout the speech. Give great attention to the crafting of your opening sentences because they will set the tone for what your audience should expect of your personality as you proceed.

I covered two presidents, LBJ and Nixon, who could no longer convince, persuade, or govern, once people had decided they had no credibility; but we seem to be more tolerant now of what I think we should not tolerate. – Helen Thomas

Logic and the Role of Arguments

“Sharia Law Billboard” by Matt57. Public domain.

We use logic every day when we construct statements, argue our point of view, and in myriad other ways. Understanding how logic is used will help us communicate more efficiently and effectively. Even if we have never formally studied logical reasoning and fallacies, we can often tell when a person’s statement doesn’t sound right. Think about the claims we see in many advertisements today—Buy product X, and you will be beautiful/thin/happy or have the carefree life depicted in the advertisement. With very little critical thought, we know intuitively that simply buying a product will not magically change our lives. Even if we can’t identify the specific fallacy at work in the argument (non causa in this case), we know there is some flaw in the argument.

In a persuasive speech, the argument will focus on the reasons for supporting your specific purpose statement. This argumentative approach is what Aristotle referred to as logos, or the logical means of proving an argument.[5]

Logic is the beginning of wisdom, not the end. – Leonard Nimoy

Logos

When offering an argument, you begin by making an assertion that requires a logical leap based on the available evidence.[6] One of the most popular ways of understanding how this process works was developed by British philosopher Stephen Toulmin.[7] Toulmin established a model that describes the structure of an argument or method of reasoning, explaining that basic arguments tend to share three common elements: claim, evidence, and warrant. The claim is an assertion that you want the audience to accept. Evidence refers to proof or support for your claim. It answers the question, “how do I know this is true?” For example, if I saw large gray clouds in the sky, I might make the claim that “it is going to rain today.” The gray clouds (evidence) are linked to rain (claim) by the warrant, an oft-unstated general connection, that large gray clouds tend to produce rain. The warrant is a connector that, if stated, would likely begin with “since” or “because.” In our rain example, if we explicitly stated all three elements, the argument would go something like this: There are large gray clouds in the sky today (evidence). Since large gray clouds tend to produce rain (warrant), it is going to rain today (claim). In this common situation, we often recognize the underlying warrant without it being explicitly stated. However, in a formal speech, having a clear warrant will increase the clarity of your argument.

To strengthen the basic argument, you will need backing for the claim. Backing provides foundational support for the claim[8] by offering examples, narratives, facts, statistics, and/or testimony, which further substantiates the argument. We discussed these kinds of support material in Chapter 8. To substantiate the rain argument we have just considered, you could explain that the color of a cloud is determined by how much light the water in the cloud is reflecting. A thin cloud has tiny drops of water and ice crystals which scatter light, making it appear white. Clouds appear gray when they are filled with large water droplets which are less able to reflect light.[9]

Claim, Evidence, Warrant

Arguments have the following basic structure:

Claim: the main proposition crafted as a declarative statement.

Evidence: the support or proof for the claim.

Warrant: the connection between the evidence and the claim.

Each component of the structure is necessary to formulate a compelling argument.

Claim: “Let’s go to Jack’s Shack for lunch.”

Evidence: “I have been there a few times and they have good servers.”

So far, your friend is highlighting service as the evidence to support their claim that Jack’s Shack is a good choice for lunch. However, the warrant is still missing. For a warrant, they need to demonstrate why good service is sufficient proof to support their claim. Remember that the warrant is the connection. For example:

Warrant: “You were a server, so I know that you really appreciate good service. I have never had a bad experience at Jack’s Shack, so I am confident that it’s a good lunch choice for both of us.”

In this case, they do a good job of both connecting the evidence to the claim and connecting the argument to their audience – you! They have selected evidence based on your previous experience as a server (likely in hopes to win you over to their claim!).

Additionally, take this example: consider the claim that “communication studies provide necessary skills to land you a job.” To support that claim, you might locate a statistic and argue that, “The New York Times had a recent article stating that 80% of jobs want good critical thinking and interpersonal skills.” It’s unclear, however, how a communication studies major would prepare someone to fulfill those needs. To complete the argument, you could include a warrant that explains, “communication studies classes facilitate interpersonal skills and work to embed critical thinking activities throughout the curriculum.” You are connecting the job skills (critical thinking) from the evidence to the discipline (communication studies) from your claim.

Despite their importance, warrants are often excluded from arguments. As speechwriters and researchers, we spend lots of time with our information and evidence, and we take for granted what we know. If you are familiar with communication studies, the connection between the New York Times statistic referenced above and the assertion that communication studies provides necessary job skills may seem obvious. For an unfamiliar audience, the warrant provides more explanation and legitimacy to the evidence.

Using “claim, evidence, and warrant” can assist you in verifying that all parts of the argumentative structure are present.

Using Evidence

With any type of evidence, there are three overarching considerations.

First, is this the most timely and relevant type of support for my claim? If your evidence isn’t timely (or has been disproven), it may drastically influence the credibility of your claim.

Second, is this evidence relatable and clear for my audience? Your audience should be able to understand the evidence, including any references or ideas within your information. Have you ever heard a joke or insight about a television show that you’ve never seen? If so, understanding the joke can be difficult. The same is true for your audience, so stay focused on their knowledge base and level of understanding.

Third, did I cherry-pick? Avoid cherry-picking evidence to support your claims. While we’ve discussed claims first, it’s important to arrive at a claim after seeing all the evidence (i.e. doing the research). Rather than finding evidence to fit your idea (cherry-picking), the evidence should help you arrive at the appropriate claim. Cherry-picking evidence can reduce your ethos and weakened your argument.