A mother takes her four-year-old to the pediatrician reporting she’s worried about the girl’s hearing. The doctor runs through a battery of tests, checks in the girl’s ears to be sure everything looks good, and makes notes in the child’s folder. Then, she takes the mother by the arm. They move together to the far end of the room, behind the girl. The doctor whispers in a low voice to the concerned parent: “Everything looks fine. But she’s been through a lot of tests today. You might want to take her for ice cream after this as a reward.” The daughter jerks her head around, a huge grin on her face, “Oh, please, Mommy! I love ice cream!” The doctor, speaking now at a regular volume, reports, “As I said, I don’t think there’s any problem with her hearing, but she may not always be choosing to listen.”

Hearing is something most everyone does without even trying. It is a physiological response to sound waves moving through the air at up to 760 miles per hour. First, we receive the sound in our ears. The wave of sound causes our eardrums to vibrate, which engages our brain to begin processing. The sound is then transformed into nerve impulses so that we can perceive the sound in our brains. Our auditory cortex recognizes a sound has been heard and begins to process the sound by matching it to previously encountered sounds in a process known as auditory association. Hearing has kept our species alive for centuries. When you are asleep but wake in a panic having heard a noise downstairs, an age-old self-preservation response is kicking in. You were asleep. You weren’t listening for the noise—unless perhaps you are a parent of a teenager out past curfew—but you hear it. Hearing is unintentional, whereas listening (by contrast) requires you to pay conscious attention. Our bodies hear, but we need to employ intentional effort to actually listen.

We regularly engage in several different types of listening. When we are tuning our attention to a song we like, or a poetry reading, or actors in a play, or sitcom antics on television, we are listening for pleasure, also known as appreciative listening. When we are listening to a friend or family member, building our relationship with another through offering support and showing empathy for her feelings in the situation she is discussing, we are engaged in relational listening. Therapists, counselors, and conflict mediators are trained in another level known as empathetic or therapeutic listening. When we are at a political event, attending a debate, or enduring a salesperson touting the benefits of various brands of a product, we engage in critical listening. This requires us to be attentive to key points that influence or confirm our judgments. When we are focused on gaining information whether from a teacher in a classroom setting, or a pastor at church, we are engaging in informational listening.

Yet, despite all these variations, Nichols called listening a “lost art.” The ease of sitting passively without really listening is well known to anyone who has sat in a boring class with a professor droning on about the Napoleonic wars or proper pain medication regimens for patients allergic to painkillers. You hear the words the professor is saying, while you check Facebook on your phone under the desk. Yet, when the exam question features an analysis of Napoleon’s downfall or a screaming patient fatally allergic to codeine you realize you didn’t actually listen. Trying to recall what you heard is a challenge, because without your attention and intention to remember, the information is lost in the caverns of your cranium.

Listening is one of the first skills infants gain, using it to acquire language and learn to communicate with their parents. Bommelje suggests listening is the activity we do most in life, second only to breathing. Nevertheless, the skill is seldom taught.

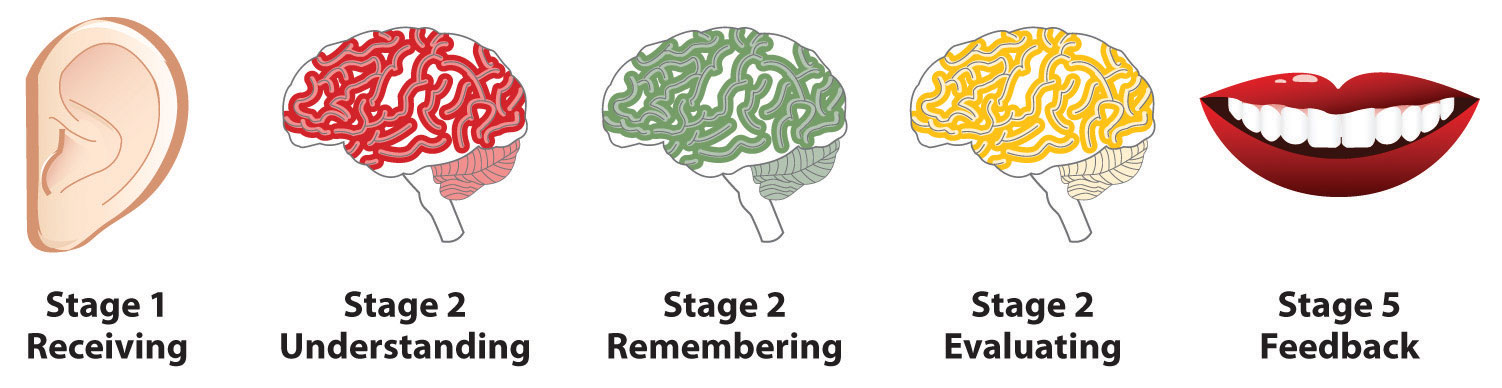

Author Joseph DeVito has divided the listening process into five stages: receiving, understanding, remembering, evaluating, and responding (DeVito, 2000).

Receiving

Receiving is the intentional focus on hearing a speaker’s message, which happens when we filter out other sources so that we can isolate the message and avoid the confusing mixture of incoming stimuli. At this stage, we are still only hearing the message. Notice in the “Stages of Listening” figure above that this stage is represented by the ear because it is the primary tool involved with this stage of the listening process.

One of the authors of this book recalls attending a political rally for a presidential candidate at which about five thousand people were crowded into an outdoor amphitheater. When the candidate finally started speaking, the cheering and yelling was so loud that the candidate couldn’t be heard easily despite using a speaker system. In this example, our coauthor had difficulty receiving the message because of the external noise. This is only one example of the ways that hearing alone can require sincere effort, but you must hear the message before you can continue the process of listening.

Understanding

In the understanding stage, we attempt to learn the meaning of the message, which is not always easy. For one thing, if a speaker does not enunciate clearly, it may be difficult to tell what the message was—did your friend say, “I think she’ll be late for class,” or “my teacher delayed the class”? Notice in the “Stages of Listening” figure that stages two, three, and four are represented by the brain because it is the primary tool involved with these stages of the listening process.

Even when we have understood the words in a message, because of the differences in our backgrounds and experience, we sometimes make the mistake of attaching our own meanings to the words of others. For example, say you have made plans with your friends to meet at a certain movie theater, but you arrive and nobody else shows up. Eventually you find out that your friends are at a different theater all the way across town where the same movie is playing. Everyone else understood that the meeting place was the “west side” location, but you wrongly understood it as the “east side” location and therefore missed out on part of the fun.

The consequences of ineffective listening in a classroom can be much worse. When professors advise students to get an “early start” on speeches, they probably hope that students will begin research right away and move on to developing a thesis statement and outlining the speech as soon as possible. However, students in your class might misunderstand the instructor’s meaning in several ways. One student might interpret the advice to mean that as long as she gets started, the rest of the assignment will have time to develop itself. Another student might instead think that to start early is to start on the Friday before the Monday due date instead of Sunday night.

So much of the way we understand others is influenced by our own perceptions and experiences. Therefore, at the understanding stage of listening we should be on the lookout for places where our perceptions might differ from those of the speaker.

Remembering

Remembering begins with listening; if you can’t remember something that was said, you might not have been listening effectively. Wolvin and Coakley note that the most common reason for not remembering a message after the fact is because it wasn’t really learned in the first place (Wolvin & Coakley, 1996). However, even when you are listening attentively, some messages are more difficult than others to understand and remember. Highly complex messages that are filled with detail call for highly developed listening skills. Moreover, if something distracts your attention even for a moment, you could miss out on information that explains other new concepts you hear when you begin to listen fully again.

It’s also important to know that you can improve your memory of a message by processing it meaningfully—that is, by applying it in ways that are meaningful to you (Gluck, et al., 2008). Instead of simply repeating a new acquaintance’s name over and over, for example, you might remember it by associating it with something in your own life. “Emily,” you might say, “reminds me of the Emily I knew in middle school,” or “Mr. Impiari’s name reminds me of the Impala my father drives.”

Finally, if understanding has been inaccurate, recollection of the message will be inaccurate too.

Evaluating

The fourth stage in the listening process is evaluating, or judging the value of the message. We might be thinking, “This makes sense” or, conversely, “This is very odd.” Because everyone embodies biases and perspectives learned from widely diverse sets of life experiences, evaluations of the same message can vary widely from one listener to another. Even the most open-minded listeners will have opinions of a speaker, and those opinions will influence how the message is evaluated. People are more likely to evaluate a message positively if the speaker speaks clearly, presents ideas logically, and gives reasons to support the points made.

Unfortunately, personal opinions sometimes result in prejudiced evaluations. Imagine you’re listening to a speech given by someone from another country and this person has an accent that is hard to understand. You may have a hard time simply making out the speaker’s message. Some people find a foreign accent to be interesting or even exotic, while others find it annoying or even take it as a sign of ignorance. If a listener has a strong bias against foreign accents, the listener may not even attempt to attend to the message. If you mistrust a speaker because of an accent, you could be rejecting important or personally enriching information. Good listeners have learned to refrain from making these judgments and instead to focus on the speaker’s meanings.

Responding

Responding sometimes referred to as feedback—is the fifth and final stage of the listening process. It’s the stage at which you indicate your involvement. Almost anything you do at this stage can be interpreted as feedback. For example, you are giving positive feedback to your instructor if at the end of class you stay behind to finish a sentence in your notes or approach the instructor to ask for clarification. The opposite kind of feedback is given by students who gather their belongings and rush out the door as soon as class is over. Notice in the “Stages of Listening” figure that this stage is represented by the lips because we often give feedback in the form of verbal feedback; however, you can just as easily respond nonverbally.

We have two ears and one tongue so that we would listen more and talk less. – Diogenes

Formative Feedback

Not all response occurs at the end of the message. Formative feedback is a natural part of the ongoing transaction between a speaker and a listener. As the speaker delivers the message, a listener signals his or her involvement with focused attention, note-taking, nodding, and other behaviors that indicate understanding or failure to understand the message. These signals are important to the speaker, who is interested in whether the message is clear and accepted or whether the content of the message is meeting the resistance of preconceived ideas. Speakers can use this feedback to decide whether additional examples, support materials, or explanation is needed.

Summative Feedback

Summative feedback is given at the end of the communication. When you attend a political rally, a presentation given by a speaker you admire, or even a class, there are verbal and nonverbal ways of indicating your appreciation for or your disagreement with the messages or the speakers at the end of the message. Maybe you’ll stand up and applaud a speaker you agreed with or just sit staring in silence after listening to a speaker you didn’t like. In other cases, a speaker may be attempting to persuade you to donate to a charity, so if the speaker passes a bucket and you make a donation, you are providing feedback on the speaker’s effectiveness. At the same time, we do not always listen most carefully to the messages of speakers we admire. Sometimes we simply enjoy being in their presence, and our summative feedback is not about the message but about our attitudes about the speaker. If your feedback is limited to something like, “I just love your voice,” you might be indicating that you did not listen carefully to the content of the message.

Hearing Impaired

Arguably, even audience members who do not possess the physiological mechanisms to hear can “listen.” Stage one (Receiving) is different because it happens through different channels (e.g., sign language, subtitles, nonverbal cues), but Stages two (Understanding/ Remembering), three (Evaluating), and four (Feedback) remain the same.

Types of Listening

We regularly engage in several different types of listening. When we are tuning our attention to a song we like, or a poetry reading, or actors in a play, or sitcom antics on television, we are listening for pleasure, also known as appreciative listening. When we are listening to a friend or family member, building our relationship with another through offering support and showing empathy for her feelings in the situation she is discussing, we are engaged in relational listening. Therapists, counselors, and conflict mediators are trained in another level known as empathetic or therapeutic listening. When we are at a political event, attending a debate, or enduring a salesperson touting the benefits of various brands of a product, we engage in critical listening. This requires us to be attentive to key points that influence or confirm our judgments. When we are focused on gaining information whether from a teacher in a classroom setting, or a pastor at church, we are engaging in comprehensive listening.

Yet, despite all these variations, Nichols called listening a “lost art.” The ease of sitting passively without really listening is well known to anyone who has sat in a boring class with a professor droning on about the Napoleonic wars or proper pain medication regimens for patients allergic to painkillers. You hear the words the professor is saying, while you check Facebook on your phone under the desk. Yet, when the exam question features an analysis of Napoleon’s downfall or a screaming patient fatally allergic to codeine you realize you didn’t actually listen. Trying to recall what you heard is a challenge, because without your attention and intention to remember, the information is lost in the caverns of your cranium.

Listening is one of the first skills infants gain, using it to acquire language and learn to communicate with their parents. Bommelje suggests listening is the activity we do most in life, second only to breathing. Nevertheless, the skill is seldom taught.

We get in our own way when it comes to effective listening. While listening may be the communication skill we use foremost in formal education environments, it is taught the least (behind, in order, writing, reading, and speaking). To better learn to listen it is first important to acknowledge strengths and weaknesses as listeners. We routinely ignore the barriers to our effective listening; yet anticipating, judging, or reacting emotionally can all hinder our ability to listen attentively.

Anticipating

Anticipating, or thinking about what the speaker is likely to say, can detract from listening in several ways. On one hand, the listener might find the speaker is taking too long to make a point and try to anticipate what the final conclusion is going to be. While doing this, the listener has stopped actively listening to the speaker. A listener who knows too much, or thinks they do, listens poorly. The only answer is humility, and recognizing there is always something new to be learned.

Anticipating what we will say in response to the speaker is another detractor to effective listening. Imagine your roommate comes to discuss your demand for quiet from noon to 4 p.m. every day so that you can nap in complete silence and utter darkness. She begins by saying, “I wonder if we could try to find a way that you could nap with the lights on, so that I could use our room in the afternoon, too.” She might go on to offer some perfectly good ideas as to how this might be accomplished, but you’re no longer listening because you are too busy anticipating what you will say in response to her complaint. Once she’s done speaking, you are ready to enumerate all of the things she’s done wrong since you moved in together. Enter the Resident Assistant to mediate a conflict that gets out of hand quickly. This communication would have gone differently if you had actually listened instead of jumping ahead to plan a response.

An expert is someone who has succeeded in making decisions and judgments simpler through knowing what to pay attention to and what to ignore. – Edward de Bono

Judging

Jumping to conclusions about the speaker is another barrier to effective listening. Perhaps you’ve been in the audience when a speaker makes a small mistake; maybe it’s mispronouncing a word or misstating the hometown of your favorite athlete. An effective listener will overlook this minor gaffe and continue to give the speaker the benefit of the doubt. A listener looking for an excuse not to give their full attention to the speaker will instead take this momentary lapse as proof of flaws in all the person has said and will go on to say.

This same listener might also judge the speaker based on superficialities. Focusing on delivery or personal appearance—a squeaky voice, a ketchup stain on a white shirt, mismatched socks, a bad haircut, or a proclaimed love for a band that no one of any worth could ever profess to like—might help the ineffective listener justify a choice to stop listening. Still, this is always a choice. The effective listener will instead accept that people may have their own individual foibles, but they can still be good speakers and valuable sources of insight or information.

Reacting Emotionally

When the speaker says an emotional trigger, it can be even more difficult to listen effectively. A guest speaker on campus begins with a personal story about the loss of a parent, and instead of listening you become caught up grieving a family member of your own. Or, a presenter takes a stance on drug use, abortion, euthanasia, religion, or even the best topping for a pizza that you simply can’t agree with. You begin formulating a heated response to the speaker’s perspective, or searing questions you might ask to show the holes in the speaker’s argument. Yet, you’ve allowed your emotional response to the speaker interfere with your ability to listen effectively. Once emotion is involved, effective listening stops.

Bore, n. A person who talks when you wish him to listen. – Ambrose Bierce

William Henry Harrison was the ninth President of the United States. He’s also recognized for giving the worst State of the Union address—ever. His two-hour speech delivered in a snowstorm in 1841 proves that a long speech can kill (and not in the colloquial “it was so good” sense). Perhaps it was karma, but after the President gave his meandering speech discussing ancient Roman history more than campaign issues, he died from a cold caught while blathering on, standing outside without a hat or coat.

Now, when asked what you know about Abraham Lincoln, you’re likely to have more answers to offer. Let’s focus on his Gettysburg Address. The speech is a model of brevity. His “of the people, by the people, for the people” is always employed as an example of parallelism, and he kept his words simple. In short, Lincoln considered his listening audience when writing his speech.

The habit of common and continuous speech is a symptom of mental deficiency. It proceeds from not knowing what is going on in other people’s minds. – Walter Bagehot

When you sit down to compose a speech, keep in mind that you are writing for the ear rather than the eye. Listeners cannot go back and reread what you have just said. They need to grasp your message in the amount of time it takes you to speak the words. To help them accomplish this, you need to give listeners a clear idea of your overarching aim, reasons to care, and cues about what is important. You need to inspire them to want to not just hear but engage in what you are saying.

Make Your Listeners Care

Humans are motivated by ego; they always want to know “what’s in it for me?” So, when you want to want to get an audience’s attention, it is imperative to establish a reason for your listeners to care about what you are saying.

Some might say Oprah did this by giving away cars at the end of an episode. But that only explains why people waited in line for hours to get a chance to sit in the audience as her shows were taped. As long as they were in the stands, they didn’t need to listen to get the car at the end of the show. Yet Oprah had audiences listening to her for 25 years before she launched her own network. She made listeners care about what she was saying. She told them what was in that episode for them. She made her audience members feel like she was talking to them about their problems and offered solutions that they could use—even if they weren’t multibillionaires known worldwide by first name alone.

Audiences are also more responsive when you find a means to tap their intrinsic motivation, by appealing to curiosity, challenging them, or providing contextualization. You might appeal to the audience’s curiosity if you are giving an informative speech about a topic they might not be familiar with already. Even in a narrative speech, you can touch on curiosity by cueing the audience to the significant thing they will learn about you or your topic from the story. A speech can present a challenge too. Persuasive speeches challenge the audience to think in a new way. Special Occasion speeches might challenge the listeners to reflect or prompt action. Providing a listener with contextualization comes back to the what’s in it for me motivation. A student giving an informative speech about the steps in creating a mosaic could simply offer a step-by-step outline of the process, or she can frame it by saying to her listener, “by the end of my speech, you’ll have all the tools you need to make a mosaic on your own.” This promise prompts the audience to sit further forward in their seats for what might otherwise be a dry how-to recitation.

Cue Your Listeners

Audiences also lean in further when you employ active voice. We do this in speaking without hesitation. Imagine you were walking across campus and saw the contents of someone’s room dumped out on the lawn in front of your dorm. You’d probably tell a friend: “The contents of Jane’s room were thrown out the window by Julie.” Wait, that doesn’t sound right. You’re more likely to say: “Julie threw Jane’s stuff out the window!” The latter is an example of active voice. You put the actor (Julie) and the action (throwing Jane’s stuff) at the beginning. When we try to speak formally, we can fall into passive voice. Yet, it sounds stuffy, and so unfamiliar to your listener’s ear that he will struggle to process the point while you’ve already moved on to the next thing you wanted to say.

Twice and thrice over, as they say, good is it to repeat and review what is good. – Plato

Knowing that your audience only hears what you are saying the one time you say it, invites you to employ repetition. Listeners are more likely to absorb a sound when it is repeated. We are often unconsciously waiting for a repetition to occur so we can confirm what we thought we heard. As a result, employing repetition can emphasize an idea for the listener. Employing repetition of a word, words, or sentence can create a rhythm for the listener’s ear. Employing repetition too often, though, can be tiresome.

If you don’t want to repeat things so often you remind your listener of a sound clip on endless loop, you can also cue your listener through vocal emphasis. Volume is a tool speakers can employ to gain attention. Certainly parents use it all of the time. Yet, you probably don’t want to spend your entire speech shouting at your audience. Instead, you can modulate your voice so that you say something important slightly louder. Or, you say something more softly, although still audible, before echoing it again with greater volume to emphasize the repetition. Changing your pitch or volume can help secure audience attention for a longer period of time, as we welcome the variety.

Pace is another speaker’s friend. This is not to be confused with the moving back and forth throughout a speech that someone might do nervously (inadvertently inducing motion sickness in his audience). Instead, it refers to planning to pause after an important point or question to allow your audience the opportunity to think about what you have just said. Or, you might speak more quickly (although still clearly) to emphasize your fear or build humor in a long list of concerns while sharing an anecdote. Alternately, you could slow down for more solemn topics or to emphasize the words in a critical statement. For instance, a persuasive speaker lobbying for an audience to stop cutting down trees in her neighborhood might say, “this can’t continue. It’s up to you to do something.” But imagine her saying these words with attention paid to pacing and each period representing a pause. She could instead say, “This. Can’t. Continue. It’s up to you. Do something.”

Convince Them to Engage

Listeners respond to people. Consider this introduction to a speech about a passion for college football:

It’s college football season! Across the nation, the season begins in late summer. Teams play in several different divisions including the SEC, the ACC, and Big Ten. Schools make a lot of money playing in the different divisions, because people love to watch football on TV. College football is great for the fans, the players, and the schools.

Now, compare it to this introduction to another speech about the same passion:

When I was a little boy, starting as early as four, my father would wake me up on Fall Saturdays with the same three words: “It’s Game Day!” My dad was a big Clemson Tigers fan, so we might drive to Death Valley to see a game. Everyone would come: my mom, my grandparents, and friends who went to Clemson too. We would all tailgate before the game—playing corn hole, tossing a foam football, and watching the satellite TV. Even though we loved Clemson football best, all college football was worth watching. You never knew when there would be an upset. You could count on seeing pre-professional athletes performing amazing feats. But, best of all, it was a way to bond with my family, and later my friends.

Both introductions set up the topic and even give an idea of how the speech will be organized. Yet, the second one is made more interesting by the human element. The speech is personalized.

The college football enthusiast speaker might continue to make the speech interesting to his listeners by appealing to commonalities. He might acknowledge that not everyone in his class is a Clemson fan, but all of them can agree that their school’s football team is fun to watch. Connecting with the audience through referencing things the speaker has in common with the listeners can function as an appeal to ethos. The speaker is credible to the audience because he is like them. Or it can work as an appeal to pathos. A speaker might employ this emotional appeal in a persuasive speech about Habitat for Humanity by asking her audience to think first about the comforts of home or dorm living that they all take for granted.

If you engage people on a vital, important level, they will respond. – Edward Bond

In speaking to the audience about the comforts of dorm living, the speaker is unlikely to refer to the “dormitories where we each reside.” More likely, she might say, “the dorms we live in.” As with electing to use active voice, speakers can choose to be more conversational than they might be in writing an essay on the same topic.

The speaker might use contractions, or colloquialisms, or make comparisons to popular television shows, music, or movies. This will help the listeners feel like the speaker is in conversation with them—admittedly a one-sided one—rather than talking at them. It can be off-putting to feel the speaker is simply reciting facts and figures and rushing to get through to the end of their speech, whereas listeners respond to someone talking to them calmly and confidently. Being conversational can help to convey this attitude even when on the inside the speaker is far from calm or confident. Nevertheless, employ this strategy with caution. Being too colloquial, for instance using “Dude” throughout the speech, could undermine your credibility. Or a popular culture example that you think is going to be widely recognized might not be the common knowledge you think it is, and could confuse audiences with non-native listeners.

Choice of attention—to pay attention to this and ignore that—is to the inner life what choice of action is to the outer. In both cases, a man is responsible for his choice and must accept the consequences, whatever they may be. – W. H. Auden

Ethical Listening

Just as you hope others are attentive to your speech, it is important to know how to listen ethically—in effort to show respect to other speakers.

Jordan stood to give his presentation to the class. He knew he was knowledgeable about his chosen topic, the Chicago Bears football team, and had practiced for days, but public speaking always gave him anxiety. He asked for a show of hands during his attention getter, and only a few people acknowledged him. Jordan’s anxiety worsened as he continued his speech. He noticed that many of his classmates were texting on their phones. Two girls on the right side were passing a note back and forth. When Jordan received his peer critique forms, most of his classmates simply said, “Good job” without giving any explanation. One of his classmates wrote, “Bears SUCK!”

As we can see from the example above, communicating is not a one-way street. Jordan’s peers were not being ethical listeners. All individuals involved in the communication process have ethical responsibilities. An ethical communicator tries to “understand and respect other communicators before evaluating and responding to their messages.” As we have learned, listening is an important part of the public speaking process. Thus, this chapter will also outline ethical listening. This section explains how to improve your listening skills and how to provide ethical feedback. Hearing happens physiologically, but listening is an art. The importance of ethical listening will be discussed first.

Develop Ethical Listening Skills

The act of hearing is what our body does physically; our ear takes in sound waves. However, when we interpret (or make sense of) those sound waves, that’s called listening. Think about the last time you gave a speech. How did the audience members act? Do you remember the people that seemed most attentive? Those audience members were displaying traits of ethical listening. An ethical listener is one who actively interprets shared material and analyzes the content and speaker’s effectiveness. Good listeners try to display respect for the speaker. Communicating respect for the speaker occurs when the listener: a) prepares to listen and b) listens with his or her whole body.

One way you can prepare yourself to listen is to get rid of distractions. If you’ve selected a seat near the radiator and find it hard to hear over the noise, you may want to move before the speaker begins. If you had a fight with your friend before work that morning, you may want to take a moment to collect your thoughts and put the argument out of your mind—so that you can prevent internal distraction during the staff meeting presentation. As a professional, you are aware of the types of things and behaviors that distract you from the speaker; it is your obligation to manage these distractions before the speaker begins.

“Bored Students” by cybrarian77. CC-BY-NC.

In order to ethically listen, it’s also imperative to listen with more than just your ears—your critical mind should also be at work. According to Sellnow, two other things you can do to prepare are to avoid prejudging the speaker and refrain from jumping to conclusions while the speaker is talking. Effective listening can only occur when we’re actually attending to the message. Conversely, listening is interrupted when we’re pre-judging the speaker, stereotyping the speaker, or making mental counterarguments to the speaker’s claims. You have the right to disagree with a speaker’s content but wait until the speaker is finished and has presented his or her whole argument to draw such a conclusion.

Ethical listening doesn’t just take place inside the body. In order to show your attentiveness, it is necessary to consider how your body is listening. A listening posture enhances your ability to receive information and make sense of a message. An attentive listening posture includes sitting up and remaining alert, keeping eye contact with the speaker and his or her visual aid, removing distractions from your area, and taking notes when necessary. Also, if you’re enjoying a particular speaker, it’s helpful to provide positive nonverbal cues like head-nodding, occasional smiling, and eye-contact. These practices can aid you in successful, ethical listening. However, know that listening is sometimes only the first step in this process—many times listeners are asked to provide feedback.

Constructive criticism is about finding something good and positive to soften the blow to the real critique of what really went on. – Paula Abdul

Provide Ethical Feedback

Ethical speakers and listeners are able to provide quality feedback to others. Ethical feedback is a descriptive and explanatory response to the speaker. Brownell explains that a response to a speaker should demonstrate that you have listened and considered the content and delivery of the message. Responses should respect the position of the speaker while being honest about your attitudes, values, and beliefs. Praising the speaker’s message or delivery can help boost his or her confidence and encourage good speaking behaviors. However, ethical feedback does not always have to be positive in nature. Constructive criticism can point out flaws of the speaker while also making suggestions. Constructive criticism acknowledges that a speaker is not perfect and can improve upon the content or delivery of the message. In fact, constructive criticism is helpful in perfecting a speaker’s content or speaking style. Ethical feedback always explains the listener’s opinion in detail. Figure 4.3 provides examples of unethical and ethical feedback.

| Figure 4.3: Unethical and Ethical Feedback |

| Unethical Feedback |

- I really enjoyed your speech.

- Your speech lacks supportive information.

- You are the worst public speaker ever.

|

| Ethical Feedback |

- I really enjoyed your speech because your topic was personally interesting to me.

- Your speech lacked supportive information. You didn’t cite any outside information. Instead, your only source was you.

- I believe your speech was ineffective because you were clearly unprepared and made no eye contact with the audience.

|

As you can see from the example feedback statements (Figure 3.3), ethical feedback is always explanatory. Ethical statements explain why you find the speaker effective or ineffective. Another guideline for ethical feedback is to “phrase your comments as personal perceptions” by using “I” language (Sellnow, 2009, p. 94). Feedback that employs the “I” pronoun displays personal preference regarding the speech and communicates responsibility for the comments. Feedback can focus on the speaker’s delivery, content, style, visual aid, or attire. Be sure to support your claims—by giving a clear explanation of your opinion—when providing feedback to a speaker. Feedback should also support ethical communication behaviors from speakers by asking for more information and pointing out relevant information. It is clear that providing ethical feedback is an important part of the listening process and, thus, of the public speaking process.

A man without ethics is a wild beast loosed upon this world. – Albert Camus