Introduction to OER

“One child, one teacher, one book, one pen can change the world.”

― Malala Yousafzai, I Am Malala: The Story of the Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban

Odds are good that we all have had at least one teacher who left a lasting impact on our lives. Perhaps that teacher greeted you with a smile each day that let you know everything would be OK, or helped you see the potential you hadn’t noticed in yourself. Maybe that teacher made learning an empowerful, engaging experience; maybe that teacher helped you see beyond your classroom and into society at large. Whatever your specific experience, you have likely encountered the power teachers have to transform lives–of their students, families, communities, and themselves.

Teaching is an increasingly complex profession. In addition to the daily instructional duties, there are planning meetings to organize, data to collect and analyze, notes and messages from administration and families to respond to, new initiatives to be informed of, meetings to attend, committees to lead, paperwork to fill out, new standards and curriculum to be evaluated, and before- and after-school duties to attend to. It can be an overwhelming set of responsibilities that do not end when students leave your classroom. On top of all of these responsibilities, there are often misconceptions about what roles teachers actually fill and how.

At the same time, it is one of the most rewarding professions. You get to watch students learn and grow over the course of a semester, a year, or even multiple semesters/years, and you get to watch yourself learn and grow with and through your students. You get to see how students solve meaningful, real-world problems in innovative ways that you never would have thought of yourself. You get to watch the human experience play out in your classroom: the joys of watching students discover their strengths and talents, the tumult of navigating social standing (in kindergarten and high school alike), and the sadness of loss. You get to try new things, grow in your own professional knowledge, and start all over again the next semester or school year. You will continue honing the science and art of teaching every year you remain in the profession.

Founding Principles of This Book

As former K-12 educators and university faculty working with pre-service teachers, we saw the need for a text that is open, applicable, backward-designed, and critical that can be used in a variety of contexts, including undergraduate introduction to education courses or educational studies programs; postgraduate programs working toward teaching credentials; pre-college teacher preparation programs (like Teacher Cadets and Teachers for Tomorrow); and more.

Open

While David Wiley first used the term “open content” in 1998 (“History of the OER Movement,” 2021) and the term Open Educational Resource (OER) was first used in 2002 at UNESCO, the OER movement has grown in popularity in recent years. According to Creative Commons (n.d.), “Open Educational Resources (OER) are teaching, learning, and research materials that are either (a) in the public domain or (b) licensed[1] in a manner that provides everyone with free and perpetual permission to engage in the 5R activities[2]” (para. 2).

While David Wiley first used the term “open content” in 1998 (“History of the OER Movement,” 2021) and the term Open Educational Resource (OER) was first used in 2002 at UNESCO, the OER movement has grown in popularity in recent years. According to Creative Commons (n.d.), “Open Educational Resources (OER) are teaching, learning, and research materials that are either (a) in the public domain or (b) licensed[1] in a manner that provides everyone with free and perpetual permission to engage in the 5R activities[2]” (para. 2).

The 5R Activities of OER are to:

- Retain: make and control a copy of the resource

- Revise: edit/modify your copy of the resource

- Remix: create something new by combining your original/revised resource with other existing material

- Reuse: publicly use your original, revised, or remixed copy of the resource

- Redistribute: share copies of your original, revised, or remixed copy of the resourcet.

A central tenet in this movement focuses on equitable access to educational materials, specifically access that is not prohibitive in cost. As textbook prices continue to rise, the OER movement recognizes that affordable (even free!) materials are necessary for students to succeed. Textbooks are not the only resources created as OER; others include open courseware, focusing on a more holistic educational experience beyond just the textbook; repositories of educational materials, where users can access OER and share or remix them; and other published materials, such as videos with Khan Academy.

Because of the interactive, digital nature of these resources, OER also allows materials to be timely, relevant, and current. Printed textbooks can take years to revise; this OER resource can be updated and re-published instantly to reflect the ever-changing nature of education.

Applicable

Because this text is OER, it allows us to incorporate unique aspects that make this work applicable. First, the Creative Commons licensing of this text (CC BY-NC-SA) allows other users to adapt this text for their context, as long as the original authors are attributed (BY); the source is not used for commercial purposes, such as selling the work (NC or Non-Commercial); and subsequent adaptations also follow the same CC BY-NC-SA license (SA or Share Alike). Therefore, you can take out pieces that aren’t applicable to you and add others that are to provide a personalized learning experience for your own specific context. Secondly, the interactive nature of OER gives you chances to apply your learning to your own personal set of experiences. You’ll find more information about that in the “Key Features” section below.

Backward-Designed

Backward design (Wiggins & McTighe, 1998) is an instructional principle that you will learn more about in Chapter 6 that involves starting with the end goal of instruction in mind. It consists of 3 key elements:

- First, identify the desired results.

- Second, decide what evidence is needed that those results have been met.

- Third, plan instruction.

Following this logic, we have started with the vision of what a competent, successful educator in the 21st century needs to know and be able to do. We then designed this text to support you in acquiring those skills and dispositions. One key area that we notice is missing in traditional “Introduction to Education” texts is asking future educators to take a critical stance, which we’ll explore together now.

Critical

Sometimes the word “critical” can carry negative connotations, but critical theory goes much deeper than getting negative feedback in a critique of a project. The basic idea behind critical theory notes that there are issues of power, access, and equity in our society that privilege some people and oppress others. Critical theory strives “to create a world which satisfies the needs and powers” of all people (Horkheimer 1972, p. 246). To create such a world, we must constantly question and challenge the existing structures of power.

Education is no exception. While we often hear of or think of education and educators as apolitical, the reality is “there is no pedagogical experience that is not political in nature” (Freire & Macedo, 1987, p. 115). Schools are microcosms of society, meaning they often mirror inequitable power structures. Whose voices are featured in required reading lists and whose are silent? How does a “Muffins for Moms” family engagement event impact a student whose mom is not in their lives, or maybe who has two moms? If a school has a high proportion of English Learners but no correspondence is sent home in families’ home languages, what message does that send about whose language matters and whose doesn’t? Why are students of color over-represented in special education programs and school punishment statistics?

As educators, we have daily opportunities to create learning environments that are welcoming and reaffirming for our students’ varied backgrounds while also interrupting inequitable power structures. One way that we can practice critical theories in our classroom is to engage in culturally relevant teaching.

Culturally Relevant Teaching

If you close your eyes and envision your quintessential American classroom, odds are good that you’ll envision desks (most likely in rows) facing a teacher’s desk at the front of the classroom, situated in front of the board. What you’re envisioning might look a lot like this.

While some of our learning might have occurred in a space that looked somewhat like this, there are a lot of important components missing. The room is set up in a way that situates the teacher as the instiller of knowledge, and the students as receivers of the teacher’s knowledge. This a concept known as the banking model of education (Freire, 1970). Think of it like a piggy bank: the piggy bank is empty until it is filled up with coins. In this case, the students are the empty piggy banks, waiting to be filled with the knowledge (coins) deposited by the teacher. Furthermore, in the image above, the room is completely devoid of any sense of community. We see white walls and a map. Where are the students–their work, their passions?

Enter culturally relevant teaching (CRT). Gloria Ladson-Billings (1994/2009) originally created this concept in the 1990s. Instead of viewing students as empty piggy banks waiting to be filled with coins of knowledge, culturally responsive teaching recognizes that students bring a variety of experiences and knowledge with them to the classroom, and that these resources can be used to design classroom experiences that are relevant to the students’ cultures and experiences. Another way to look at culturally relevant teaching is to “teach to and through [students’] personal and cultural strengths, their intellectual capabilities, and their prior accomplishments” (Gay, 2010, p. 26).

Critical Lens: Variations on CRT

There are many different terms for this type of teaching: culturally responsive teaching (CRT), culturally relevant pedagogy (CRP), culturally sustaining pedagogy, culturally and linguistically relevant pedagogy, and more. While there are slight differences among these theories and approaches, the overall idea is the same: powerful learning occurs when we recognize the knowledge, backgrounds, languages, and experiences that our students bring with them to our classrooms and design instruction around these elements.

Ladson-Billings (1995, 2001) established three key pillars of culturally relevant teaching.

- Academic success: For teachers to embrace culturally responsive teaching, they have to believe that all students are capable of academic success. This belief involves setting high–but attainable–academic expectations for all students. Unfortunately, students who come from minoritized backgrounds (students of color, students from poverty, and more) sometimes are held to lower standards than their peers, which then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy–those students don’t perform as well because of the lack of high academic expectations. However, high expectations aren’t helpful if they aren’t attainable. Just like you would not ask a couch potato to run a marathon tomorrow, you can’t ask a student to advance multiple years’ worth of academic skills–or even one year’s worth–without proper scaffolds and support.

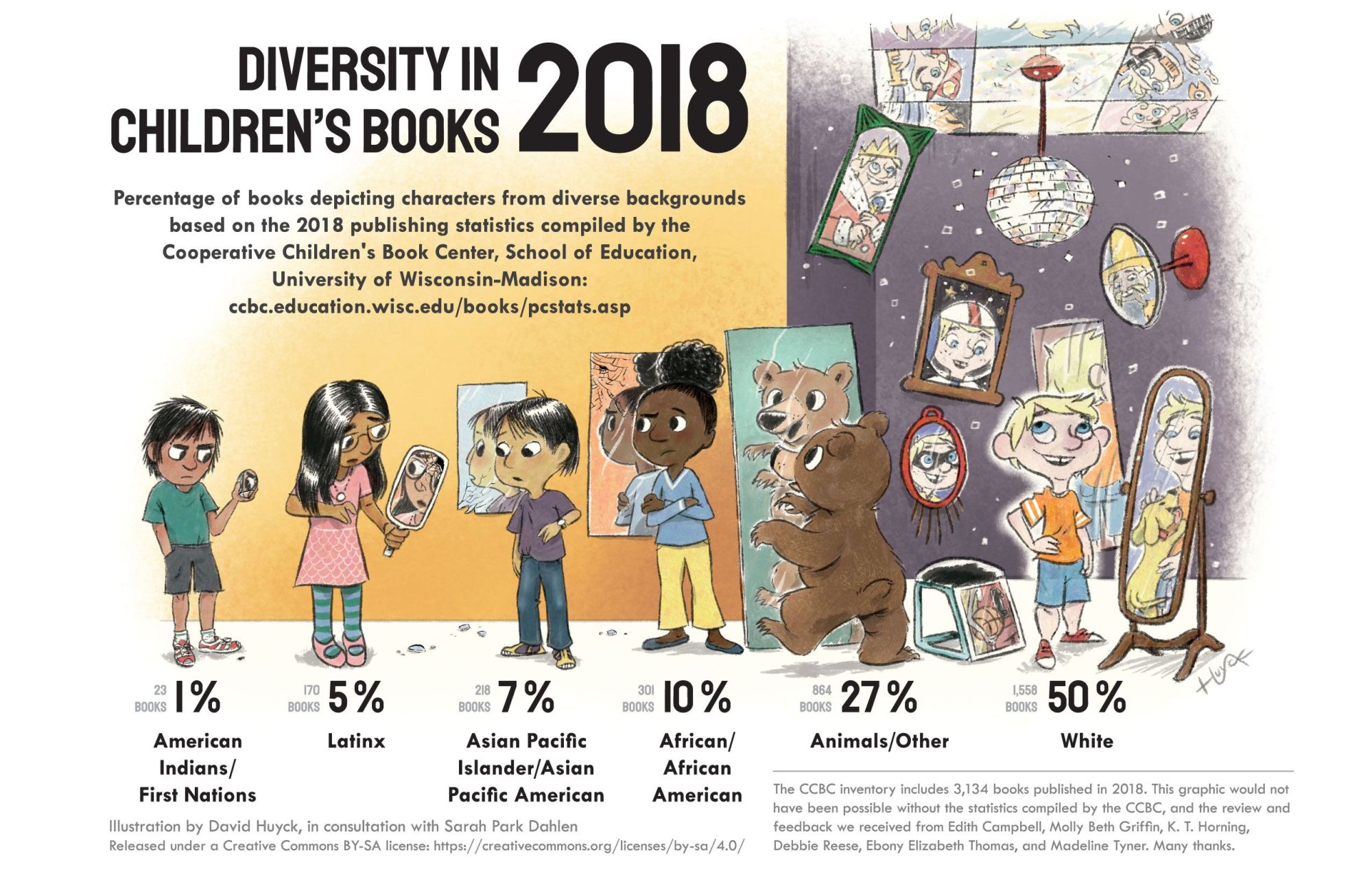

- Cultural competence: Being a culturally competent teacher means you recognize that your own culture, worldview, and understanding does not necessarily reflect your students’. Being culturally competent is especially vital when we look at the demographics of today’s schools. Students are increasingly diverse, but the profile of teachers remains somewhat the same. In the United States, only 20% of teachers are not White (Geiger, 2018).

- Sociopolitical consciousness: Being a teacher with sociopolitical consciousness means you are willing to acknowledge and critique inequities. An inequity occurs when some people have certain benefits that others don’t have. For example, throughout the history of the United States, rules, laws, and social norms have given more power to people with certain characteristics–such as being White, male, heterosexual, and at least middle-class–than people with other characteristics, such as being a person of color, transgender, or poor. Some of these rules and norms have prevented groups of people from earning money, buying property, going to school, and more–all elements that affect a person’s ability to be successful for years and generations to come. Acknowledging and critiquing these inequities is an important part of culturally relevant teaching.

Beyond these three key pillars, there is no one “right way” to do culturally relevant teaching. You might make sure you have a classroom library full of books that reflect your students and worlds beyond your students’ own worlds (though this is an ongoing challenge!). You might make sure that your math problems have real-world applications and use names from your students’ families and friends. You might make sure that you are teaching multiple sides of history, instead of just the “winning side” (who, again, tends to be the people with more power, as explained above). There is no set curriculum that you must use to be a culturally relevant teacher. Instead, being a culturally relevant teacher involves aligning yourself with the three pillars above and knowing your students. In addition, a culturally responsive classroom has a feeling of community in the classroom. Everyone supports one other’s success in a culturally responsive classroom.

While the thought of culturally relevant teaching might be overwhelming right now, especially if you have not experienced this yourself as a learner, there are clear benefits from approaching your teaching this way. Gay (2010) described the potential of culturally responsive teaching as:

- validating,

- comprehensive,

- multidimensional,

- empowering,

- transformative, and

- emancipatory.

Looking back at the classroom pictured earlier in this chapter, you can see how such an environment would have a very hard time inspiring any of these characteristics!

To that end, we have a responsibility to look at some of our own privileges as authors of this text. We both identify as White women. Dr. Wells grew up in a middle-class household that put a lot of emphasis on success in school yielding future attendance at college. Dr. Clayton grew up in a family that also valued education, including the expectation of a college degree. While different pieces of our identities combine in different ways to make each of us the individuals that we are (we will talk more about this concept of intersectionality in Ch. 1), we both do benefit from certain privileges and positions of power. Sometimes this can make us overlook ways that we could be more culturally relevant teachers. The important thing to remember is that being a culturally relevant teacher is an ongoing process of learning and implementing instruction that builds off of our knowledge of our own students.

Stop & Investigate

If you’d like to learn more about culturally relevant teaching (CRT), here are some high-quality resources.

- Delpit, L. (2012). “Multiplication is for white people”: Raising expectations for other people’s children. The New Press.

- Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

- Howard, T. C. (2010). Why race and culture matter in schools: Closing the achievement gap in America’s classrooms. Teachers College Press.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Nieto, S. (2009). The light in their eyes: Creating multicultural learning communities. Teachers College Press.

- Paris, D., & Alim, H.S. (2017). Culturally sustaining practice: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. Teachers College Press.

Key Features

Each chapter will feature similar structures to guide your learning, such as the following.

- Unlearning: Aligning with a framework that causes us to question and challenge knowledge that is taken for granted, each chapter will open with a common misunderstanding related to the topic of that chapter.

- Multimodal content: As 21st century learners, we take in information from a variety of “texts,” not just printed words. Therefore, we will incorporate videos, websites, podcasts, and more throughout the book to keep you engaged with the content in current and innovative ways.

- Critical Lens Boxes: Each chapter features Critical Lens Boxes to push your thinking about equity from multiple perspectives, often tied to current events and real-world application.

Conclusion

Now that you have a feel for how this text is organized and what frameworks underlie it, we are ready to explore the Introduction to Education text. Whether you are choosing to become a teacher or just want to learn more about the field of education, you are making an important step to be an advocate and informed stakeholder of education by engaging in this text. Congratulations, and welcome to the world of teaching!

Teaching, learning, and research materials that are either (a) in the public domain or (b) licensed in a manner that provides everyone with free and perpetual permission to retain, revise, remix, reuse, or redistribute those resources.

Planning concept designed by Wiggins & McTighe (1998) that involves identifying desired results and then working backward to design assessment and instruction.

Approach of constructing meaning through recognizing issues of power, access, and equity; often involves questioning and challenging the status quo.

Student-centered approach to teaching created by Ladson-Billings (1994/2009) with three key pillars: academic success, cultural competence, and sociopolitical consciousness.

Term coined by Crenshaw (1989) meaning many different aspects of identity--including race, economic class, gender, and more--overlap and intersect with one another.