9 Key Theories of Learning and Development

“He is just so lazy – sits there and refuses to do any work. And his parents are no help – they never return phone calls or emails. Why bother?”

This is an actual statement by a teacher frustrated with a fourth grader in her classroom. What this teacher did not know was the context in which the student was living. He was homeless and living out of his mother’s car. His mother couldn’t pay her cell phone bill, so had no way of receiving phone calls or emails. The teacher failed to realize what else could be contributing to his “laziness”: hunger, fear, lack of adequate care, and a parent unavailable to him with her own struggle to survive.

In order to teach our students, we have to know them. Multiple influences affect our students and their environments.

Chapter Outline

In this chapter, we will investigate how different systems influence learning and we will explore two theoretical perspectives on development.

Systems that Influence Student Learning

As humans grow and develop, there are many different systems that influence this development. Think about systems as interrelated parts of a whole, just like the solar system is made up of planets and other celestial objects. Two theories that consider various impacts on student learning are Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

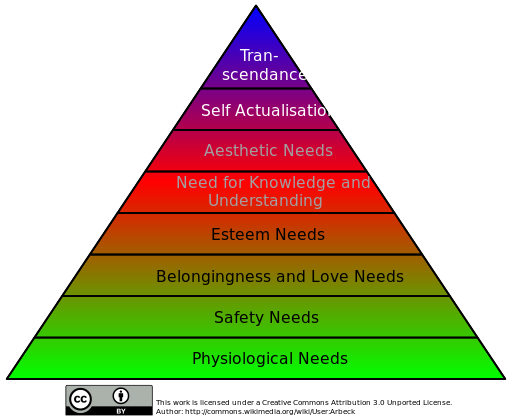

One way to conceptualize influences on student learning is through need systems. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (see Figure 2.2) theorized that people are motivated by a succession of hierarchical needs (McLeod, 2020). Originally, Maslow discussed five levels of needs shaped in the form of a pyramid. He later adjusted the pyramid to include eight levels of needs, incorporating need for knowledge and understanding, aesthetic needs, and transcendence. Figure 2.2 depicts these eight needs in hierarchical order. The first four levels are deficiency needs, and the upper four are growth needs. The first four are essential to a student’s well being, and they build on each other. These deficiency needs must be satisfied before a person can move on to the growth needs. Moving to the growth needs is essential for learning to truly occur. Now we will examine each of the elements within Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in more depth.

Of the eight levels, the first is physiological needs. These needs include food, water, and shelter. In this case, do students have a home where they are properly nourished? If not, students who are not attending to their work may be hungry, not just daydreaming. This is why free and reduced breakfast and lunch programs are so essential in schools.

Safety and security needs are the second level of the pyramid. Students need to feel that they are not in harm’s way. Schools are responsible for maintaining safe environments for students and classrooms need to feel safe and secure. This requires classroom rules that all students follow, including protecting students from bullying and threatening behavior. There are effective and less effective ways to structure a classroom so that it is safe for all students.

The third level of Maslow’s hierarchy is love and belonging. In schools, these needs are met primarily through positive relationships with teachers and peers, and people with whom students regularly interact. Feelings of acceptance are necessary here, and teachers can play a huge role in creating these feelings for students. It is critical that teachers are non-judgmental towards their students. It does not matter how you, as a teacher, may feel about a student’s lifestyle choices, beliefs, political views or family structures; it matters how a student perceives you as someone who accepts them, no matter what.

The fourth and final level of deficiency needs is esteem needs: self-worth and self-esteem. Students must have experiences in schools and classrooms that lead them to feel positive about themselves. Self-esteem is what students think and feel about themselves, and it contributes to their confidence. Self-worth is students knowing that they are valuable and lovable.

Figure 2.2: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Following the four deficiency needs in Maslow’s hierarchy are growth needs. Once students reach growth needs, they are ready for true, meaningful learning. The fifth element, the need to know and understand, is also referred to as cognitive needs. It is our job as educators to motivate students to want to know and understand the world around them. In order to do this, we must be sure we are providing our students with questions that move them to higher-order thinking skills. An instructional model that is well-developed and utilized in many classrooms is Bloom’s Taxonomy. It can be used to classify learning objectives, and it is a way to encourage students to think more deeply about content and motivate them to want to know more.

The sixth level of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is aesthetic needs. At this level, we can learn to appreciate the beauty of the natural world. When we are focused on deficiency needs in the lower levels of Maslow’s theory, it is more difficult to see the beauty in our environment and surroundings. In education, students need to be exposed to the beauty that is reflected in the arts: music, visual arts and theatre. Most schools separate these into distinct periods or blocks; however, it is essential that arts are also integrated into the curriculum. Additionally, students should be exposed to arts outside of Western art so they encounter art forms that include representations of all cultures, including their own.

Self-actualization is the seventh need on the pyramid and is another growth need. Maslow indicated that this happens as we age. It is our intrinsic need to make the most of our lives and reach our full potential. A way of thinking about this is to consider what we think of our ideal selves–or, for young people, how they see themselves or what they see themselves having achieved and broadly experienced as they get to later stages in life.

Finally, transcendence needs are the highest on Maslow’s hierarchy. Maslow (1971) stated, “transcendence refers to the very highest levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos” (p. 269). Though most of us in K-12 schools will not experience students at this level, it is important to note that this is the goal in life, according to Maslow.

Critical Lens: Origins of Theories

Sometimes we hold theories as universal truths without stopping to consider the context in which they were made. For example, Bridgman, Cummings, and Ballard (2019) recently investigated the origin of Maslow’s theory and discovered that he himself never created the well-known pyramid model to represent the hierarchy of needs. Furthermore, there are concerns that Maslow appropriated his theory from the Siksika (Blackfoot) Nation. Dr. Cindy Blackstock (Gitksan First Nation member, as cited in Michel, 2014) explains the Blackfoot belief involves a tipi with three levels: self-actualization at the base; community actualization in the middle; and cultural perpetuity at the top. Maslow visited the Siksika Nation in 1938 and published his theory in 1943. Bray (2019) explains more about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and its alignment with the Siksika Nation. You should be informed of Maslow’s hierarchy, but you should also be aware that critiques of this theory exist.

Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences

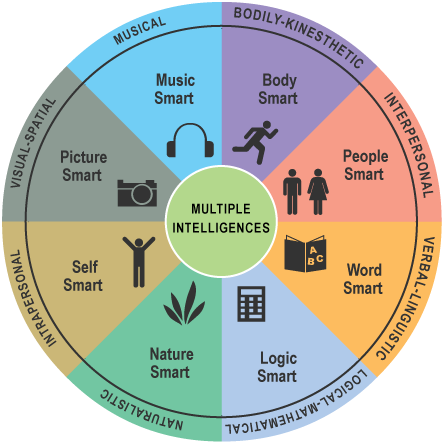

Teachers need to determine students’ areas of strength and need to allow students to work and grow in those areas. One approach to doing this is to determine students’ strengths in different intelligence areas. Theorist Howard Gardner (2004, 2006) initially proposed eight multiple intelligences (see Figure 2.3), but he later added two more areas: existential and moral intelligence. Though there is little educational research evidence to support instructing students in these eight intelligences (for example, you should not plan a lesson eight different ways to address all eight intelligences in one lesson!), Gardner’s goal was to ensure that teachers did not just focus on verbal and mathematical intelligences in their teaching, which are two very common foci of instruction in schools.

Figure 2.3: Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences

Similarly, while we often can hear reference to learning styles (often including visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic, or VARK), they have no research-based support. Instead, “people’s approaches to learning can, do, and should vary with context. Rather than assessing and labeling students as particular kinds of learners and planning accordingly, a wise teacher will do the following:

- Offer students options for learning and expressing learning

- Help them reflect on strategies for mastering and using critical content

- Guide them in knowing when to modify an approach to learning when it proves to be inefficient or ineffective in achieving the student’s goals” (Sousa & Tomlinson, 2018, p. 161-162).

Learn more about the myth of learning styles in the video below.

Theoretical Perspectives on Development

While all human beings are unique and grow, learn, and change at different rates and in different ways, there are some common trends of development that impact the trajectories our students follow. Two foundational theories of development are Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory.

Cognitive Developmental Theory: Piaget

Cognitive developmental theorists such as Jean Piaget posit that we move from birth to adulthood in predictable stages (Huitt & Hummel, 2003). These theorists argue these stages of development do not vary and are distinct from one other. While rates of progress vary by child, the sequence is the same and skipping stages is impossible. Therefore, progression through stages is essentially similar for each child.

In 1936, Piaget proposed four stages of cognitive development for children:

- the sensorimotor stage, which ranges from birth to age two;

- the preoperational stage, ranging from age two through age six or seven;

- the concrete operational stage, ranging from age six or seven through age 11 or 12;

- and the formal operational stage, ranging from age 11 or 12 through adulthood.

Piaget argued that key abilities are acquired at each stage. We will now look at each stage in depth, along with videos demonstrating these abilities in action.

In the sensorimotor stage, little children learn about their surroundings through their senses. In addition, the idea of object permanence is emphasized. This is a child’s realization that things continue to exist even if they are not in view. An example is when parents play peek-a-boo with their infants. The child sees that the parent or caregiver is actually gone when the parent’s or caregiver’s hands are in front of their faces. The video below demonstrates the idea of object permanence.

In the preoperational stage, children develop language, imagination, and memory, working toward symbolic thought. One of the key ideas is the principle of conservation, meaning that specific properties of objects remain the same even if other properties change. The notion of centration is critical here in that children only pay attention to one aspect of a situation. An example is filling a shallow round container with water, then pouring the same amount of water into a skinny container. The child in the preoperational stage will say that there is now more water in the skinny container, even though no additional liquid was added. The video below demonstrates the principle of conservation.

Additionally, in the preoperational stage, Piaget suggested that children have egocentric thinking, meaning that they lack the ability to see situations from another person’s point of view. The video below demonstrates the idea of egocentrism.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OinqFgsIbh0&feature=related

In the concrete operational stage, children begin to think more logically and abstractly and can now master the idea of conservation as they work toward operational thought. Children in this stage are less egocentric than before. Key developments in this stage include the notions of reversibility, which is defined as the ability to change direction in linear thinking to return to starting point, and transitivity, which is the ability to infer relationships between two objects based upon objects’ relation to a third object in serial order. The video below demonstrates the ideas of reversibility and transitivity.

Finally, the formal operational stage continues through adulthood. This is when we can better reason and understand hypothetical situations as we develop abstract thought. Key ideas include metacognition, which is the ability to monitor and think about your own thinking; and the ability to compare abstract relationships, such as to generate laws, principles, or theories. The video below demonstrates the idea of hypothetical thinking, where we see how a boy in the concrete operational stage and a woman in the formal operations stage respond to the same scenario.

In addition to his four stages of cognitive development for children, Piaget also discussed how we add new information to our existing understandings. Key terms in his conceptualization of cognitive constructivism include schema, assimilation, accommodation, disequilibrium, and equilibrium. Schema refers to the ways in which we organize information as we confront new ideas. For example, children learn what a wallet is and that it generally contains money. Next they learn that a wallet can be carried in various places, i.e. a pocket or a purse. The child is making a connection now between the idea of a wallet and the category of places where it can be carried. The child’s schema is developing as ideas begin to interconnect and form what we can call a blueprint of concepts and their connections.

In order to develop schema, Piaget would have said that children (and all of us) need to experience disequilibrium. Children are in a state of equilibrium as they go about in the world. As they encounter a new concept to add to their schema, they experience disequilibrium where they need to process how this new information fits into their schema. They do this in two ways: assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation uses existing schema to interpret new situations. Accommodation involves changing schema to accommodate new schema and return to a state of equilibrium. Let’s try an example. A child knows that banging a fork on a table makes noise, and the fork does not break. That child and concept are in a state of equilibrium, with the existing schema of knowing banging things on tables does not break the item. The next day, a parent gives the child a sippy cup. The child bangs it on the table and it also does not break, so the child assimilates this new object into their existing understanding that banging items on tables does not break the item. One day, a parent gives the child an egg. The child proceeds to bang it on the table, but what happens? The egg breaks, sending the child’s schema–everything that they bang on the table remains unbroken–into a state of disequilibrium. That child must accommodate that new information into their schema. Once this new information is accommodated, the child can once again move into equilibrium. The video below explains the idea of schema, assimilation and accommodation.

Sociocultural Theory: Vygotsky

Whereas Piaget viewed learning in specific stages where children engage in cognitive constructivism (Huitt & Hummel, 2003), thus emphasizing the role of the individual in learning, Lev Vygotsky viewed learning as socially constructed (Vygotsky, 1986). Vygotsky was a Russian psychologist in the 1920s and 1930s, but his work was not known to the Western world until the 1970s. He emphasized the role that other people have in an individual’s construction of knowledge, known as social constructivism. He realized that we learned more with other people than we learned all by ourselves.

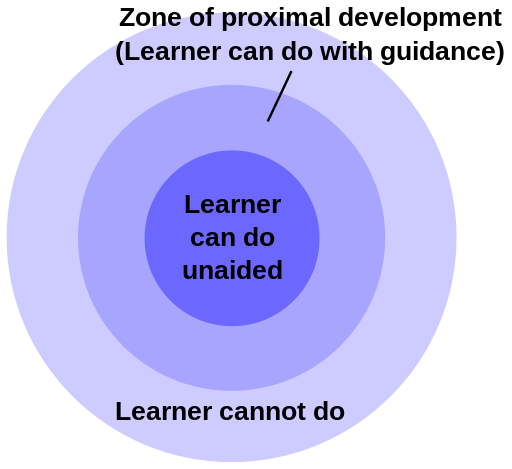

One of the major tenets in Vygotsky’s theory of learning (Vygotsky, 1986) is the zone of proximal development. As shown in Figure 2.4, the zone of proximal development (ZPD) is the difference between what a learner can do without help and what they can do with help.

Figure 2.4: Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

Vygotsky’s often-quoted definition of zone of proximal development says ZPD is “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). The concept of scaffolding is closely related to the ZPD. Scaffolding is a process through which a teacher or more competent peer gives aid to the student in her/his ZPD as necessary, and tapers off this aid as it becomes unnecessary, much as a scaffold is removed from a building during construction. While we often think of a teacher as the more “expert other” in ZPD, this individual does not have to be a teacher. In fact, sometimes our own students are the more “expert other” in certain areas. Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory emphasizes that we can learn more with and through each other.

CRITICAL LENS: CONTEXT MATTERS

As we examine these four theories, it is also important to analyze the context of this work: these theorists and researchers all identified as White, often working with individuals close to them to conduct research (for example, Piaget studied his own children). We all absorb certain beliefs and social norms from our communities, so knowing that these theories came from communities that represented fairly limited diversity is important.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we surveyed two systems that influence students’ learning (Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences) and two theoretical perspectives on development (Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory).

As we saw in the Unlearning Box at the beginning of this chapter, all of our students bring different characteristics with them to our classrooms. While some (not all!) students may share certain characteristics and overall developmental trajectories, teachers must acknowledge that each student in the classroom has individual strengths and needs. Only once we know our students as individual learners will we be able to teach them effectively.

Succession of 8 hierarchical needs, divided into deficiency needs (physiological, safety, belongingness & love, and esteem needs) and growth needs (need for knowledge & understanding, aesthetic needs, self actualization, and transcendence).

Framework designed by Benjamin Bloom and colleagues in 1956, and later revised in 2001. Divides educational goals/cognitive processes into six categories of increasing complexity: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and create.

Theory created by Howard Gardner in 2004. The eight multiple intelligences include musical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, verbal-linguistic, logical-mathematical, naturalistic, intrapersonal, and visual-spatial.

Often associated with visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic (VARK) input of information. In actuality, learning styles have no research-based support and are a myth.

Cognitive developmental theorist who identified four stages of cognitive development in children: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational.

First stage in Piaget's cognitive development from ages birth to two in which young children learn about their world through their senses.

Second stage in Piaget's cognitive developmental theory in which children between the ages of 2 and 6 or 7 develop language, imagination, and memory, working toward symbolic thought.

Third stage of Piaget's theory of cognitive development in which children between the ages of 6 or 7 through 11 or 12 begin to think more logically and abstractly as they work toward operational thought.

Fourth stage in Piaget's theory of cognitive development in which children aged 11 or 12 through adulthood develop better reasoning and abstract thinking skills.

Realization that things continue to exist even if they are not in view. Developed during the sensorimotor stage of cognitive development, according to Piaget.

Understanding developed during the preoperational stage of Piaget's cognitive developmental theory that specific properties of objects remain the same even if other properties change.

Characteristic of the preoperational stage of Piaget's cognitive developmental theory in which children focus on only one aspect of a situation.

Worldview developed during the preoperational stage of Piaget's cognitive developmental theory that means children see the world from their own perspective and not other points of view.

Understanding developed during the concrete operational stage of Piaget's cognitive developmental theory that allows children to change direction in linear thinking to return to a starting point.

Understanding developed during the concrete operational stage of Piaget's cognitive developmental theory that allows children to infer relationships between two objects based on objects' relation to a third object in serial order.

Ability to monitor and think about your own thinking.

Ways in which we organize information as we confront new ideas.

In Piaget's cognitive developmental theory, a new experience that forces children to accommodate or assimilate existing schema.

In Piaget's theory of cognitive development, the balance achieved when schema align with experiences.

In Piaget's theory of cognitive development, use of existing schema to interpret new situations.

In Piaget's theory of cognitive development, changing schema to accommodate new information or experiences. In special education, a change to learning materials, the environment, or an assessment that does not fundamentally change the curriculum expectation or lower the standard of performance for the student.

Act of constructing understanding of the world through cognitive development. Piaget's concepts of schema, equilibrium, disequilibrium, assimilation, and accommodation are parts of cognitive constructivism.

Russian psychologist and sociocultural theorist who created the zone of proximal development.

Approach toward learning that centers social interactions as opportunities for constructing new knowledge. Vygotsky's sociocultural theory and zone of proximal development are examples of social constructivism.

According to Vygotsky, the difference between what a learner can do without help and what they can do with help.