5 Schools in the United States

As a student, you may have enjoyed going to school with friends who lived in your neighborhood. But did you know that where you live also can impact how well-funded and well-resourced your school is? Because schools get much of their funding from property taxes, areas with more expensive houses have higher taxes, resulting in more school funding. While the United States believes education should be accessible to all, where you live can determine which resources will or will not be available to benefit your learning.

This chapter describes models of schools present in the United States today, including their funding, enrollment policies, and key characteristics. Different models of schools, varying configurations of classrooms and instructional models are presented and the variety of schools in the United States offers some families the option of school choice, including charter schools and vouchers.

Chapter Outline

Models of Schools

One central tenet of the U.S. education system is that all people in our country deserve access to education, regardless of the language you speak, how much money you make, where you live, or the color of your skin. Some other countries employ tracking, which means that certain individuals are channeled into certain educational “tracks” based on their perceived capabilities for future success. Tracking limits access to education for certain groups of people. In the United States, all children and youth have access to K-12 educational opportunities.

CRITICAL LENS BOX: TRACKING

While the U.S. does not “track” students in the ways some other countries do, we do still engage in some forms of tracking. For example, you may have heard of–or even experienced–ability grouping. This term refers to placing students in homogeneous groups by ability levels. In secondary school, tracking may result in college prep, honors, or AP-level courses. Historically, these different curricula were developed when more Black and working-class students were entering schools, and elite educational opportunities were reserved for upper-middle-class students, who were often White, wanting to attend college (Education Week, 2004). Therefore, tracking “quickly took on the appearance of internal segregation” (para. 2), which is a problem since racial discrimination in education is illegal. So, while U.S. educational systems do not force a student into a specific educational track for a specific career at an early age like some countries do, tracking by ability level is still a harmful practice in many U.S. schools. Teachers need to be aware of potential biases toward students in certain tracked groups (i.e., AP students are “good” and college prep students are “bad”).

The majority of schools in the United States fall into one of two categories: public or private. A public school is defined as any school that is maintained through public funds to educate children living in that community or district for free. The structure and governance of a public school varies by model, but shares the characteristics of being free and open to all applicants within a defined boundary. A private school is defined as a school that is privately funded and maintained by a private group or organization, not the government, usually by charging tuition. Private schools may follow a philosophy or viewpoint different from public schools; for example, many private schools are governed by religious institutions.

There are a variety of public school models, including traditional, charter, magnet, Montessori, virtual, alternative, and language immersion. Private school models include traditional, religious, parochial, Montessori, Waldorf, virtual, boarding, and international schools. Some school models may be public or private. Table 4.1 includes a breakdown of school models, their funding source, and key characteristics.

Table 5.1: School Models by Funding, Enrollment, and Key Characteristics

| School Model | Public or Private | Enrollment | Key Characteristics |

| Traditional Public | Public | Open/School Boundary Lines | State and local governance, policy and curriculum. |

| Magnet | Public | Open across school district/Application or lottery | Specializes in program (art, science, math, etc), promotes diversity across a district. |

| Alternative | Public | Students that cannot attend traditional school due to a variety of factors. | State and local governance, policy and curriculum. Small class sizes and alternative scheduling. Individualized support. |

| Language Immersion/ Bilingual | Both | Open across school district/Application | A portion of instruction is taught in a language other than English. Students are immersed in a second language for part of instruction. |

| Charter | Both | Open across school district/Application or lottery | Autonomous from local and state authority as long as the school meets charter mission and performance measures. |

| Montessori | Both | Open across school district/Application | Philosophy that children need connection to the environment. Focuses on real life experiences. |

| Waldorf | Private | Application/Tuition | Believes each child has unique potential that should be developed through education to better humanity as a whole. While not specifically religious, Waldorf schools are based on general spirituality. Focuses on imagination and fantasy. |

| Virtual | Both | Open across school district/Application | The majority of instruction is provided in an online environment. |

| Traditional Private | Private | Application/Tuition | Curriculum decided upon by the governing body (board, organization, or company). May be non-profit or for profit. |

| Religious | Private | Application/Tuition | Mission is to teach religious values in addition to teaching core curriculum. |

| Parochial | Private | Application/Tuition | Mission is to teach religious values in addition to teaching core curriculum. School is sponsored by a local church through funding. |

| Boarding | Private | Application/Tuition | Community of scholars, artists, and athletes. School provides food and housing. |

| International | Private | Application/Tuition | Follows a curriculum different from that of the country in which the school is physically located. May use International Baccalaureate curriculum, among others. Students consist of a diverse population that is often highly mobile. |

| Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) | Public | Serves military and Department of Defense dependents serving overseas and in the U.S. U.S. contractor dependents may attend for a fee. | Follows a standard curriculum across schools. Makes up the 10th largest school district in the U.S. Consists of two parallel districts: Department of Defense Dependents Schools (DoDDS) operating in Europe and the Pacific and Department of Defense Domestic Dependent Elementary and Secondary Schools operating in the Americas. |

One type of school not listed in the table is homeschool. Homeschooling is a type of schooling that would not fall into either the public or private category. Homeschooling is defined as a child not enrolling in a public or private school, but receiving an education at home. Each state has its own rules and regulations that families must follow and report on if homeschooling. For example, the Virginia Department of Education (2021) requires that families inform the school division of their decision to homeschool their child, update the school district with the student’s annual academic progress, and provide evidence that the homeschool instructor (such as a parent) meets specific qualifications to fill the role. For information about homeschooling in Tennessee, follow this link: https://www.tn.gov/education/school-options/home-schooling-in-tn.html

Enrollment Policies

In addition to the schools being separated by their funding source, schools are defined by their process of enrollment. The majority of public schools operate on two basic enrollment guidelines: boundary or open. Districts with enrollment policies using school boundary lines allow all students within a geographic area to enroll in the school. If a school has an open enrollment policy, then the school will also allow students from other geographic areas within the district to enroll if space permits. School boundary lines are often highly politicized. Schools are publicly rated and this affects everything from property values to the quality of teachers recruited. Ratings may be based on data sources like the school report card, which may include data on teacher education levels, teacher retention, student demographics, student performance on standardized tests, and student and teacher attendance rates. However, ratings also can be culturally biased: one nonprofit rating site called GreatSchools ( https://www..org/ ) , which often is integrated into online realtor websites as families are choosing where to move, redid their rating formula in 2017 after it realized that their previous rating system prioritized schools in predominantly White neighborhoods (Barnum & LeMee, 2019).

Critical Lens: Redlining

Although the Supreme Court made segregated schools illegal in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, you will see many schools today that continue to have student populations that are separated by race or socioeconomic status. This trend is due to a practice called redlining, in which housing was allowed or denied in certain areas based on people’s race or socioeconomic status. The impacts of redlining are ongoing de facto segregation, which means that while overt segregation was outlawed, it still continues in other ways.

Some public school models, including charter, magnet, and language immersion, may have more students desiring to apply than there is space. In these schools, applications or lotteries may be used. An application system allows the schools to choose students based on characteristics, such as grades, demographic diversity, or geographic area. Often these schools are looking for high-achieving students or have a mission of diversifying the school. A lottery system gives each student that has applied an equal chance of attending and is decided by randomly selecting names from the pool of students.

Key Characteristics

Schools also differ in several key characteristics beyond funding and enrollment. One key characteristic of schools is what individuals or entities provide supervision or oversight of the school’s functioning. A school’s ability to follow curriculum (how instruction is organized and managed) and policies (such as rules, expectations, and norms that school community members must follow) is directly tied to their funding.

For the majority of public schools (excluding charter schools), state and local entities supervise curriculum and policies. In private schools, boards, organizations, or companies often supervise curriculum and policies. In addition, a school’s curriculum is often defined by its mission or philosophy. Schools may differ in how curriculum is presented or in specialized programs. For example, language immersion schools present standardized curriculum in two languages, while magnet schools place an emphasis on a certain part of the curriculum like science or art. Religious schools may focus on presenting curriculum based on a religious viewpoint or values.

Season 2: Episode 6 – A Reckoning (Link to Podcast)

Season 2: Episode 6 – A Reckoning (Link to Podcast)

Classroom/Instructional Models

Within each school a variety of classroom models may be utilized. Traditionally, schools have different grade levels with a different teacher for each grade. However, some schools may incorporate multi-age classrooms. Multi-age classrooms allow for students of different grades to be in one class. For example, students in second and third grade may be combined in one classroom. While this may seem difficult to manage, a traditional classroom model does not guarantee that all students with the same chronological age will be at the same developmental stage. Children develop at different rates and have different academic skill levels. Many multi-age classrooms recognize this and are able to provide both homogeneous and heterogeneous groupings in the classroom. When students are grouped homogeneously for small group lessons, a younger student may benefit from instruction at a higher level that they may not have had access to at their grade level. Heterogeneous grouping of students also provides peer modeling and support from more advanced students (Carter, 2005).

Many multi-age classrooms and traditional classroom models utilize co-teaching. Co-teaching is when teachers are paired up in a classroom and share the responsibility of planning, teaching, and assessing students. Having more than one teacher in a classroom provides additional support for students that need one-on-one instruction or additional supports. This is often seen in classrooms where special education or bilingual teachers are paired with a classroom teacher to make instruction for students with disabilities or English Language Learners more inclusive. Co-teaching also may elevate instruction by having two teachers plan together. The division of teaching responsibilities may present itself in a variety of ways, including the following: one teacher teaches and the other observes, one teaches and one drifts, teachers teach at stations, team teaching (both tag team at teaching same lesson), and parallel teaching (class is divided into two groups that receive the same instruction simultaneously) (Trites, 2017).

Sometimes an individual teacher may loop with their students. Looping occurs when a classroom teacher moves with a group of students from grade to grade. For example, a teacher may have a group of students for third grade, and then move with them to fourth grade. Early looping, or teacher cycling, has foundations in one-room schoolhouses. In the early 1900s, looping was also promoted in urban school districts as a way to improve relationships between students and teachers. Looping is also a key component of Waldorf schools. Looping may increase student-teacher relationships and family-teacher relationships, but it also may increase instructional time from year to year. When teachers loop with students, the classroom routines and structure remain the same, so valuable instructional time is not spent on teaching new routines and classroom structure. Teachers may also spend less time on initial assessment of students. Research has shown that when teachers loop, less retention and referral of students occurs (Grant, Richardson & Forsten, 2000). For looping to be successful, a teacher must feel comfortable teaching across grade levels and be seen as effective. If a teacher is ineffective, then students looping would be at a disadvantage. A teacher wanting to loop may also have difficulty doing so if it is not common in their school or district. Many teachers only teach one grade, but if a third-grade teacher loops to fourth grade, it means a fourth-grade teacher at the school must also be willing to leave that grade level.

Different classroom and teaching models vary from school to school and district to district. Multi-age classrooms, co-teaching, and looping may be implemented by choice, or as a way to consolidate or expand resources. For example, multi-age classrooms may help schools save space when classroom space is limited within the physical school. These practices may also help students when academic or developmental needs are highly diverse. If a school has a large percentage of children that are academically diverse, then dividing them by chronological age may not be appropriate. These decisions are often made at the school level by the principal.

With so many school models available in the U.S., how do families choose which type of school their child should attend? School choice is a complex issue for families to navigate. What may be best for one student is not always best for another. The choices for students also vary by geographic and socioeconomic boundaries. Many families make school decisions based on the following factors:

- transportation and distance to chosen school;

- cost or tuition of school;

- curriculum and programs available;

- religious affiliation; and

- fit for the individual student.

Families in some areas of the U.S. have greater access to the different models of schools. Small rural towns may only have one school within the immediate area. However, federal reform policies, such as No Child Left Behind (NCLB), have increased the number of charter schools and use of vouchers.

School Choice

With so many school models available in the U.S., how do families choose which type of school their child should attend? is a complex issue for families to navigate. What may be best for one student is not always best for another. The choices for students also vary by geographic and socioeconomic boundaries. Many families make school decisions based on the following factors:

- transportation and distance to chosen school;

- cost or tuition of school;

- curriculum and programs available;

- religious affiliation; and

- fit for the individual student.

Families in some areas of the U.S. also have greater access to the different models of schools presented at the beginning of this chapter than others. Small rural towns may only have one school within the immediate area. However, federal reform policies, such as No Child Left Behind (NCLB), have increased the number of charter schools and use of vouchers.

Charter Schools

In 2001, when NCLB was signed into law, federal and state funds required schools to make an Annual Yearly Progress (AYP) report, based on assessment data. Schools that did not meet AYP for two consecutive years were often required to earmark money for student tutoring or allow students to transfer. When a student transfers, the school’s funding formula decreases by one student, resulting in a loss of funds for the school. If a school continues to not meet AYP, then the school may be closed. When a school is closed, it often becomes a charter school (Brookhart, 2013).

As shown earlier in Table 4.1, charter schools are often publicly funded, but they do not have the same requirements as a traditional public school. When a student transfers out of a traditional school to a charter school, the funds follow the student. Charter schools are autonomous from public schools and to operate must meet the educational goals set forth in their charter. Charter school admittance is also application based, usually being first come, first served or by lottery. In 2010, charter schools comprised six percent of public school students, but now the number is closer to 30 percent in some localities (Prothero, 2018).

Why does it matter if public schools become charter schools? In many regions, like Minneapolis-St. Paul, California, and Texas, charter schools are more segregated than the public schools within those same boundaries, which were already highly segregated (Institute on Race and Poverty, 2008). Because charter schools rely on applications for admission, parent participation in the admission process also separates students by socioeconomics (Frankenberg et al., 2011).

Vouchers

One reason that school choice has become so politicized is the use of school vouchers. School vouchers are defined as “a government-supplied coupon that is used to offset tuition at an eligible private school” (Epple et al., 2017, p. 441). In the 1960s, some of the first school vouchers were awarded to promote desegregation. School voucher policies and programs today vary across localities and are present in over thirty states. Students who receive vouchers enroll in a private school, which receives those funds. The voucher may cover tuition in full, or offset it significantly. This video explains some of the pros and cons of vouchers.

Voucher Funding

Vouchers are funded by one of the following: tax revenues, tax credits, or by private organizations (Epple et al., 2017). The majority of states that use tax revenues to fund their vouchers provide vouchers to under-resourced students. For example, Milwaukee, Cleveland, New Orleans, and Washington, DC provide vouchers to students whose family income is just above the poverty line. Some areas, such as in Ohio and Indiana, provide vouchers using tax revenues to all students in failing school districts.

Some states (including Florida, Iowa, Georgia, Indiana, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island) utilize tax credits to fund vouchers. Businesses in these states that fund vouchers are provided a tax credit. For example, Florida businesses can receive 100 percent corporate tax income credit up to $559.1 million dollars (EdChoice, 2019). In addition to tax revenues and tax credits, many states also have privately funded voucher programs. One notable voucher program is the Children’s Scholarship Fund, which was founded with contributions from the Walton Family Foundation (Epple et al., 2017).

Voucher Outcomes

When a student uses a voucher to attend a private school, this changes the funding formulas for a local school. This student is no longer included in the funding formula for the LEA or SEA. This means that the local and state budget is lowered because one less student is being counted in that funding formula. School vouchers are provided and promoted to give under-resourced students school choice, but not all students have equal opportunities.

Public schools allow and are required by law to provide services for all students. While policies prohibit private schools from discriminating against students based on race, many religious private schools may consider religious affiliation, sexual orientation (except Maryland, which has laws prohibiting private schools utilizing vouchers to do so), and disability in their admission decisions. Private schools are not exempt from discrimination laws, but the application process allows them to choose which students to admit. For example, a private school receiving government funds must provide students with disabilities with accommodations, unless these accommodations change the philosophy of the academic program, or create “significant difficulty or expense.” A large portion of private schools do not hire teachers trained to provide accommodations; thus, many claim they do not have the resources to serve students with disabilities. Vouchers are not beneficial for students with disabilities that cannot attend private schools, but vouchers also hinder these students further by diverting funds from the public schools, who do provide these services, when other students use vouchers.

Conclusion

While many individuals and groups call for school reform in order to provide equity to all students, the process is complex. School choice and the varied school models within the U.S. also makes school reform highly political. While families are given the right to choose their own child’s education, many families’ choices are constrained by geographic and economic resources. The landscape of schools in the U.S. is constantly changing, but one principle will remain as the foundation of schools in this country: everyone deserves access to education.

"To me education is a leading out of what is already there in the pupil’s soul." – Muriel Spark

As a life-long learner, teachers will continue to research the origins of education and schooling. In doing so, we better understand how education has evolved and predict or advise reform efforts more accurately. In this section an introduction to the history of schooling and education in the United States is provided. While a this section covers vast amounts of educational history, it is just a 'taste' of the rich history of teaching in America.

"To me education is a leading out of what is already there in the pupil’s soul." – Muriel Spark

As a life-long learner, teachers will continue to research the origins of education and schooling. In doing so, we better understand how education has evolved and predict or advise reform efforts more accurately. In this section an introduction to the history of schooling and education in the United States is provided. While a this section covers vast amounts of educational history, it is just a 'taste' of the rich history of teaching in America.

"Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel."

– Socrates

- Discuss how organized schooling evolved in the United States

- Introduce Horace Mann and the advent of common schools

- Discuss key terms including Dame schools, McGuffey Readers, Kindergarten, Latin & English Grammar Schools and segregation

- Define and explain the impact of the Old Deluder Satan Act, the Morrill Acts, Plessy v. Ferguson, and Brown v. Board of Education.

"Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel."

– Socrates

- Discuss how organized schooling evolved in the United States

- Introduce Horace Mann and the advent of common schools

- Discuss key terms including Dame schools, McGuffey Readers, Kindergarten, Latin & English Grammar Schools and segregation

- Define and explain the impact of the Old Deluder Satan Act, the Morrill Acts, Plessy v. Ferguson, and Brown v. Board of Education.

Education in early America was hardly formal. During the colonial period, the Puritans in what is now Massachusetts required parents to teach their children to read and also required larger towns to have an elementary school, where children learned reading, writing, and religion. In general, though, schooling was not required in the colonies, and only about 10% of colonial children, usually just the wealthiest, went to school, although others became apprentices (Urban, Jennings, & Wagoner, 2008).

To help unify the nation after the Revolutionary War, textbooks were written to standardize spelling and pronunciation and to instill patriotism and religious beliefs in students. At the same time, these textbooks included negative stereotypes of Native Americans and certain immigrant groups. The children going to school continued primarily to be those from wealthy families. By the mid-1800s, a call for free, compulsory education had begun, and compulsory education became widespread by the end of the century. This was an important development, as children from all social classes could now receive a free, formal education. Compulsory education was intended to further national unity and to teach immigrants “American” values. It also arose because of industrialization, as an industrial economy demanded reading, writing, and math skills much more than an agricultural economy had.<

At least two themes emerge from this brief history. One is that until very recently in the record of history, formal schooling was restricted to wealthy males. This means that boys who were not white and rich were excluded from formal schooling, as were virtually all girls, whose education was supposed to take place informally at home. Today, as we will see, race, ethnicity, social class, and, to some extent, gender continue to affect both educational achievement and the amount of learning occurring in schools.

Second, although the rise of free, compulsory education was an important development, the reasons for this development trouble some critics (Bowles & Gintis, 1976; Cole, 2008). Because compulsory schooling began in part to prevent immigrants’ values from corrupting “American” values, they see its origins as smacking of ethnocentrism. They also criticize its intention to teach workers the skills they needed for the new industrial economy. Because most workers were very poor in this economy, these critics say, compulsory education served the interests of the upper/capitalist class much more than it served the interests of workers. It was good that workers became educated, say the critics, but in the long run their education helped the owners of capital much more than it helped the workers themselves. Whose interests are served by education remains an important question addressed by sociological perspectives on education, to which we now turn.

History of Education

The following is the video ED Sessions 2.0 with Andy Smarick from the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation.If the video does not show up below you can view it on YouTube by clicking this link.

How to Escape Education's Death Valley

In this video Sir Ken Robinson outlines 3 principles crucial for the human mind to flourish — and how current education culture works against them. In a funny, stirring talk he tells us how to get out of the educational "death valley" we now face, and how to nurture our youngest generations with a climate of possibility.

Attribution for photo: Joel Dorman Steele and Esther Baker Steele

Education in early America was hardly formal. During the colonial period, the Puritans in what is now Massachusetts required parents to teach their children to read and also required larger towns to have an elementary school, where children learned reading, writing, and religion. In general, though, schooling was not required in the colonies, and only about 10% of colonial children, usually just the wealthiest, went to school, although others became apprentices (Urban, Jennings, & Wagoner, 2008).

To help unify the nation after the Revolutionary War, textbooks were written to standardize spelling and pronunciation and to instill patriotism and religious beliefs in students. At the same time, these textbooks included negative stereotypes of Native Americans and certain immigrant groups. The children going to school continued primarily to be those from wealthy families. By the mid-1800s, a call for free, compulsory education had begun, and compulsory education became widespread by the end of the century. This was an important development, as children from all social classes could now receive a free, formal education. Compulsory education was intended to further national unity and to teach immigrants “American” values. It also arose because of industrialization, as an industrial economy demanded reading, writing, and math skills much more than an agricultural economy had.<

At least two themes emerge from this brief history. One is that until very recently in the record of history, formal schooling was restricted to wealthy males. This means that boys who were not white and rich were excluded from formal schooling, as were virtually all girls, whose education was supposed to take place informally at home. Today, as we will see, race, ethnicity, social class, and, to some extent, gender continue to affect both educational achievement and the amount of learning occurring in schools.

Second, although the rise of free, compulsory education was an important development, the reasons for this development trouble some critics (Bowles & Gintis, 1976; Cole, 2008). Because compulsory schooling began in part to prevent immigrants’ values from corrupting “American” values, they see its origins as smacking of ethnocentrism. They also criticize its intention to teach workers the skills they needed for the new industrial economy. Because most workers were very poor in this economy, these critics say, compulsory education served the interests of the upper/capitalist class much more than it served the interests of workers. It was good that workers became educated, say the critics, but in the long run their education helped the owners of capital much more than it helped the workers themselves. Whose interests are served by education remains an important question addressed by sociological perspectives on education, to which we now turn.

History of Education

The following is the video ED Sessions 2.0 with Andy Smarick from the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation.If the video does not show up below you can view it on YouTube by clicking this link.

How to Escape Education's Death Valley

In this video Sir Ken Robinson outlines 3 principles crucial for the human mind to flourish — and how current education culture works against them. In a funny, stirring talk he tells us how to get out of the educational "death valley" we now face, and how to nurture our youngest generations with a climate of possibility.

Attribution for photo: Joel Dorman Steele and Esther Baker Steele

desire to learn is hammering on cold iron." - Horace Mann

Horace Mann, American Educational Reformer

Horace Mann was an influential reformer of education, responsible for the introduction of common schools - non-sectarian public schools open to children of all backgrounds - in America.

Early Public Schools in the United States

There were several key actions taken by the federal government to finance public education early in our nation's history, including Land Grants. Click here for a brief review.

After the American Revolution, an emphasis was put on education, especially in the northern states, which rapidly established public schools. By the year 1870, all states had free elementary schools and the U.S. population boasted one of the highest literacy rates at the time. Private academies flourished in towns across the country, but rural areas (where most people lived) had few schools before the 1880s. By the close of the 1800s, public secondary schools began to outnumber private ones.

The earliest public schools were formed in the nineteenth century, where they became known as common schools. This term was coined by educational reformer Horace Mann and refers to the aim of these schools to serve individuals of all social classes and religions.

The Common School

Students often went to common schools from ages six to fourteen, although this could vary widely. The duration of the school year was often dictated by the agricultural needs of particular communities, with children having time off from studies when they would be needed on the family farm. These schools were funded by local taxes, did not charge tuition, and were open to all children - at least, all white children. Typically, with a small amount of state oversight, each district was controlled by an elected local school board, traditionally with a county school superintendent or regional director elected to supervise day-to-day activities of several common school districts.

Since common schools were locally controlled and the United States was very rural in the nineteenth century, most common schools were small one-room centers. They usually had a single teacher who taught all of the students together, regardless of age. Common school districts were nominally subject to their creator, either a county commission or a state regulatory agency.

Typical curricula consisted of "The Three Rs" (reading, writing, and arithmetic), as well as history and geography. There were wide variations in grading (from 0-100 grading to no grades at all), but end-of-the-year recitations were a common way that parents were informed about what their children were learning.

Many education scholars mark the end of the common school era around 1900. In the early 1900s schools generally became more regional (as opposed to local), and control of schools moved away from elected school boards and towards professionals.

Dame Schools

Essential to the development of education in the United States was the creation of Dame Schools. Read the linked article to better understand their purpose.

Old Deluder Satan Law

Most notable in the history of education in America are the Massachusetts School Laws. These included the Old Deluder Satan Law, with which you should be familiar. Click and review both linked items.

McGuffey Readers

More trivia that education students may find interesting, the McGuffey Readers were the first 'textbooks.' Conduct your own online search to learn more about these booklets and see authentic images.

Kindergarten

While kindergarten is expect in schooling today, that wasn't always the case. Click here to learn how kindergarten evolved.

Latin & English Grammar School

Designed as prep schools, these boy-only schools were unique. See this article for details. There are even a few still open.

Key Legal Cases that Shaped Schooling in America

Review these law cases which were pivotal in the evolution of America's educational system:

- Morrill Act and see this link

- Plessy v. Ferguson

- de jure school segregation: segregation that is imposed by law

- de facto school segregation: segregation occurring because of factors other than a law

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Here is an excellent timeline of American educational history. For a great overview of education during colonial times, review this!

desire to learn is hammering on cold iron." - Horace Mann

Horace Mann, American Educational Reformer

Horace Mann was an influential reformer of education, responsible for the introduction of common schools - non-sectarian public schools open to children of all backgrounds - in America.

Early Public Schools in the United States

There were several key actions taken by the federal government to finance public education early in our nation's history, including Land Grants. Click here for a brief review.

After the American Revolution, an emphasis was put on education, especially in the northern states, which rapidly established public schools. By the year 1870, all states had free elementary schools and the U.S. population boasted one of the highest literacy rates at the time. Private academies flourished in towns across the country, but rural areas (where most people lived) had few schools before the 1880s. By the close of the 1800s, public secondary schools began to outnumber private ones.

The earliest public schools were formed in the nineteenth century, where they became known as common schools. This term was coined by educational reformer Horace Mann and refers to the aim of these schools to serve individuals of all social classes and religions.

The Common School

Students often went to common schools from ages six to fourteen, although this could vary widely. The duration of the school year was often dictated by the agricultural needs of particular communities, with children having time off from studies when they would be needed on the family farm. These schools were funded by local taxes, did not charge tuition, and were open to all children - at least, all white children. Typically, with a small amount of state oversight, each district was controlled by an elected local school board, traditionally with a county school superintendent or regional director elected to supervise day-to-day activities of several common school districts.

Since common schools were locally controlled and the United States was very rural in the nineteenth century, most common schools were small one-room centers. They usually had a single teacher who taught all of the students together, regardless of age. Common school districts were nominally subject to their creator, either a county commission or a state regulatory agency.

Typical curricula consisted of "The Three Rs" (reading, writing, and arithmetic), as well as history and geography. There were wide variations in grading (from 0-100 grading to no grades at all), but end-of-the-year recitations were a common way that parents were informed about what their children were learning.

Many education scholars mark the end of the common school era around 1900. In the early 1900s schools generally became more regional (as opposed to local), and control of schools moved away from elected school boards and towards professionals.

Dame Schools

Essential to the development of education in the United States was the creation of Dame Schools. Read the linked article to better understand their purpose.

Old Deluder Satan Law

Most notable in the history of education in America are the Massachusetts School Laws. These included the Old Deluder Satan Law, which you should be familiar. Click and review both linked items.

McGuffey Readers

More trivia that education students may find interesting, the McGuffey Readers were the first 'textbooks.' Conduct your own online search to learn more about these booklets and see authentic images.

Kindergarten

While kindergarten is expect in schooling today, that wasn't always the case. Click here to learn how kindergarten evolved.

Latin & English Grammar School

Designed as prep schools, these boy-only schools were unique. See this article for details. There are even a few still open.

Key Legal Cases that Shaped Schooling in America

Review these law cases which were pivotal in the evolution of America's educational system:

- Morrill Act and see this link

- Plessy v. Ferguson

- de jure school segregation: segregation that is imposed by law

- de facto school segregation: segregation occurring because of factors other than a law

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Here is an excellent timeline of American educational history. For a great overview of education during colonial times, review this!

“What the educator does in teaching is to make it possible for the students to become themselves” (Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed). David Simon, in his book Social Problems and the Sociological Imagination: A Paradigm for Analysis (1995), points to the notion that social problems are, in essence, contradictions—that is, statements, ideas, or features of a situation that are opposed to one another. Consider then, that one of the greatest expectations in U.S. society is that to attain any form of success in life, a person needs an education. In fact, a college degree is rapidly becoming an expectation at nearly all levels of middle-class success, not merely an enhancement to our occupational choices. And, as you might expect, the number of people graduating from college in the United States continues to rise dramatically.

The contradiction, however, lies in the fact that the more necessary a college degree has become, the harder it has become to achieve it. The cost of getting a college degree has risen sharply since the mid-1980s, while government support in the form of Pell Grants has barely increased. The net result is that those who do graduate from college are likely to begin a career in debt. As of 2013, the average of amount of a typical student’s loans amounted to around $29,000. Added to that is that employment opportunities have not met expectations. The Washington Post (Brad Plumer May 20, 2013) notes that in 2010, only 27 percent of college graduates had a job related to their major. The business publication Bloomberg News states that among twenty-two-year-old degree holders who found jobs in the past three years, more than half were in roles not even requiring a college diploma (Janet Lorin and Jeanna Smialek, June 5, 2014).

Is a college degree still worth it? All this is not to say that lifetime earnings among those with a college degree are not, on average, still much higher than for those without. But even with unemployment among degree-earners at a low of 3 percent, the increase in wages over the past decade has remained at a flat 1 percent. And the pay gap between those with a degree and those without has continued to increase because wages for the rest have fallen (David Leonhardt, New York Times, The Upshot, May 27, 2014).

But is college worth more than money?

Generally, the first two years of college are essentially a liberal arts experience. The student is exposed to a fairly broad range of topics, from mathematics and the physical sciences to history and literature, the social sciences, and music and art through introductory and survey-styled courses. It is in this period that the student’s world view is, it is hoped, expanded. Memorization of raw data still occurs, but if the system works, the student now looks at a larger world. Then, when he or she begins the process of specialization, it is with a much broader perspective than might be otherwise. This additional “cultural capital” can further enrich the life of the student, enhance his or her ability to work with experienced professionals, and build wisdom upon knowledge. Two thousand years ago, Socrates said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” The real value of an education, then, is to enhance our skill at self-examination.

References

Leonhardt, David. 2014. “Is College Worth It? Clearly , New Data Say.” The New York Times. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

Lorin Janet, and Jeanna Smialek. 2014. “College Graduates Struggle to Find Eployment Worth a Degree.” Bloomberg. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

New Oxford English Dictionary. “contradiction.” New Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

Plumer, Brad. 2013. “Only 27 percent of college graduates have a job related ot their major.” The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

Simon, R David. 1995. Social Problems and the Sociological Imagination: A Paradigm for Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Education in the United States is a massive social institution involving millions of people and billions of dollars. About 75 million people, almost one-fourth of the U.S. population, attend school at all levels. This number includes 40 million in grades pre-K through 8, 16 million in high school, and 19 million in college (including graduate and professional school). They attend some 132,000 elementary and secondary schools and about 4,200 2-year and 4-year colleges and universities and are taught by about 4.8 million teachers and professors (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab Education is a huge social institution.

Correlates of Educational Attainment

About 65% of U.S. high school graduates enroll in college the following fall. This is a very high figure by international standards, as college in many other industrial nations is reserved for the very small percentage of the population who pass rigorous entrance exams. They are the best of the brightest in their nations, whereas higher education in the United States is open to all who graduate high school. Even though that is true, our chances of achieving a college degree are greatly determined at birth, as social class and race/ethnicity have a significant effect on access to college. They affect whether students drop out of high school, in which case they do not go on to college; they affect the chances of getting good grades in school and good scores on college entrance exams; they affect whether a family can afford to send its children to college; and they affect the chances of staying in college and obtaining a degree versus dropping out. For these reasons, educational attainment depends heavily on family income and race and ethnicity.

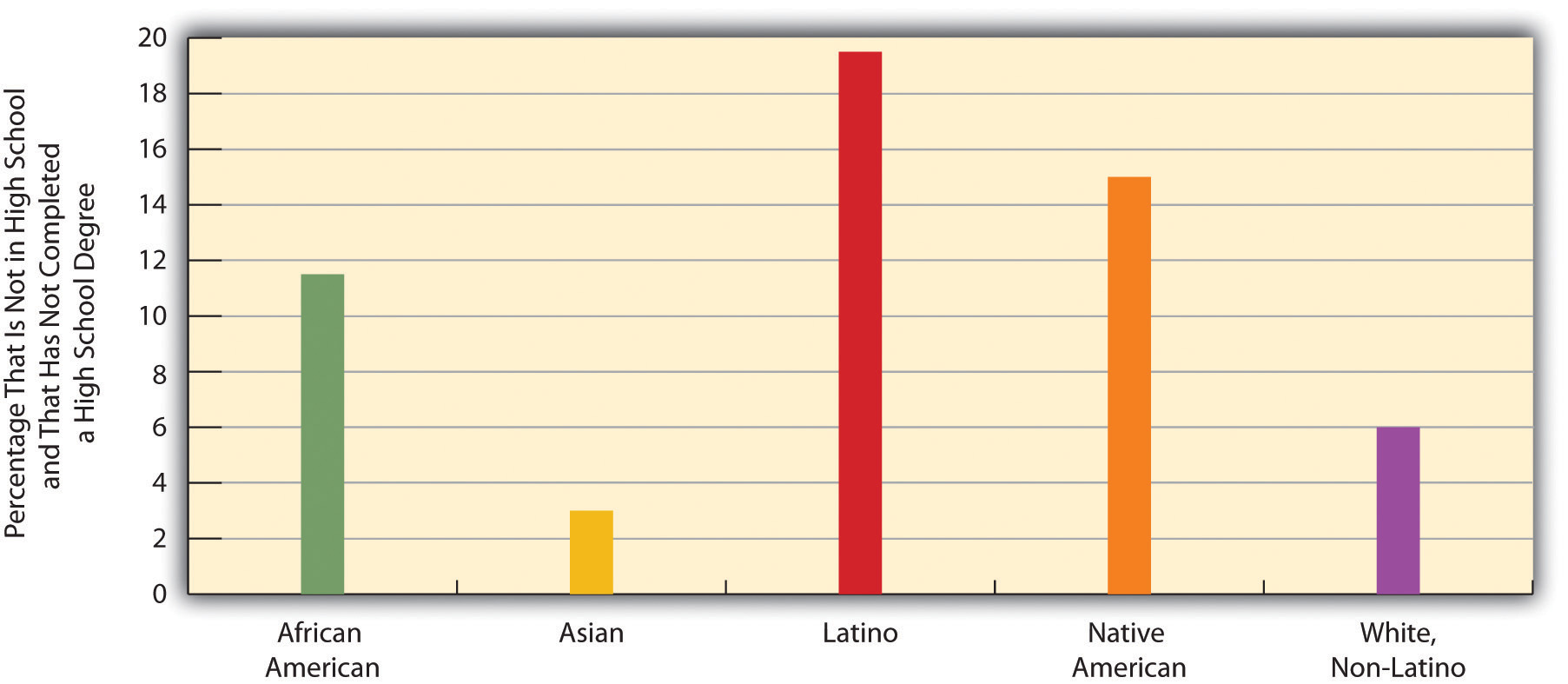

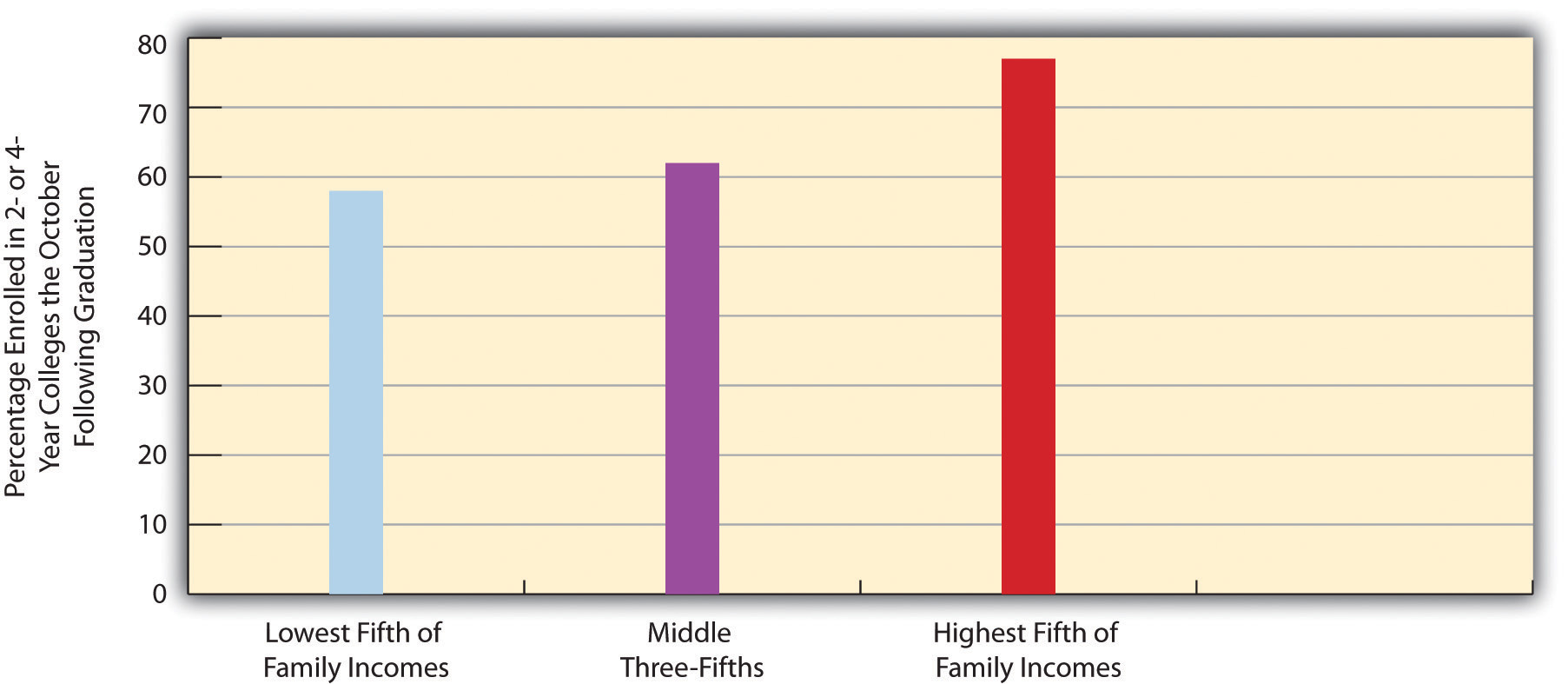

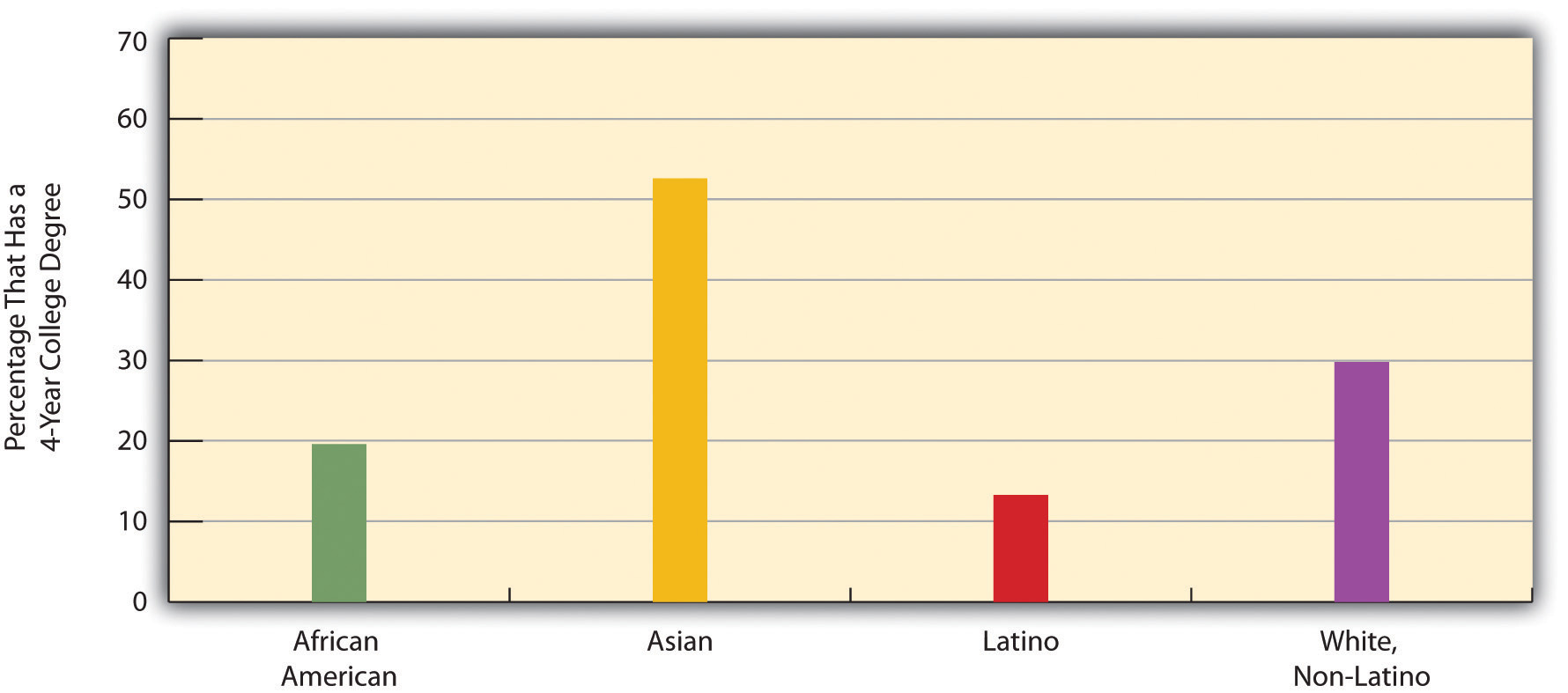

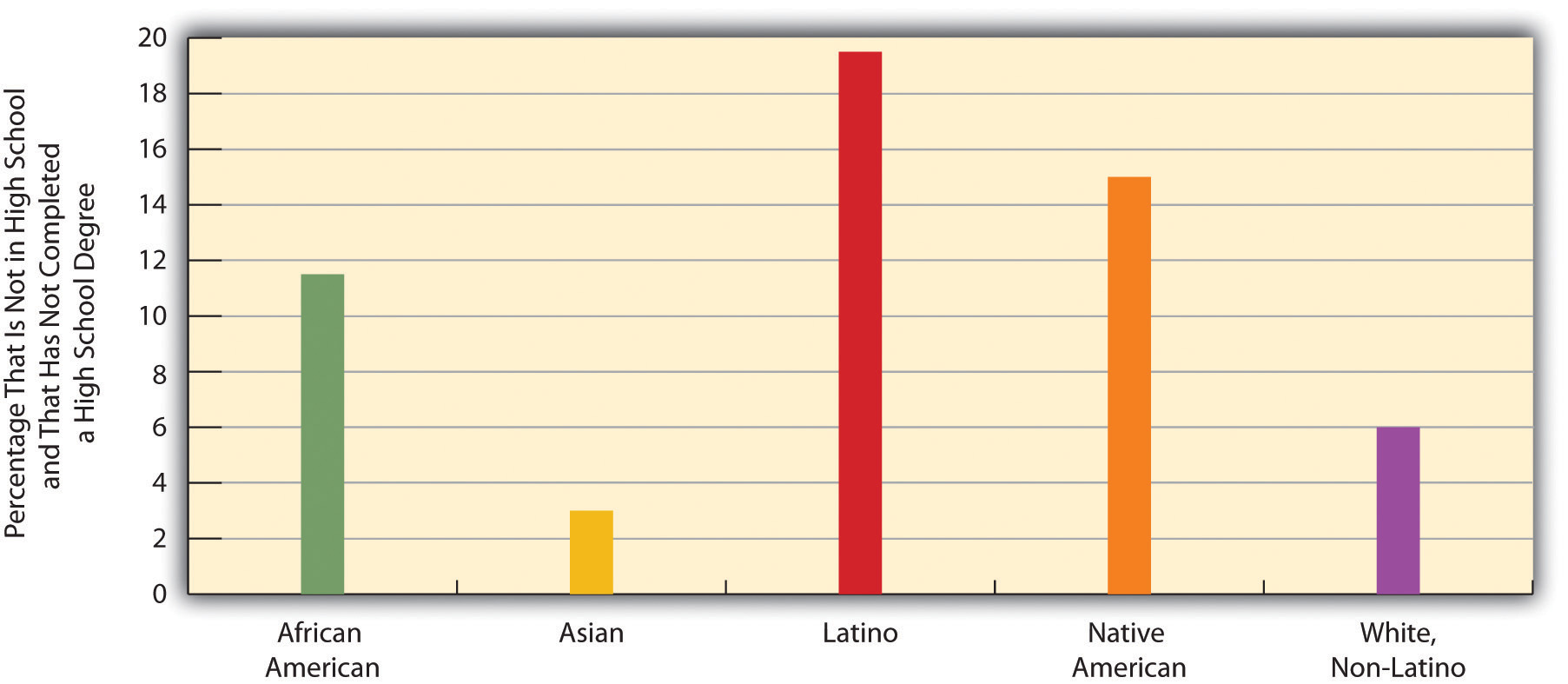

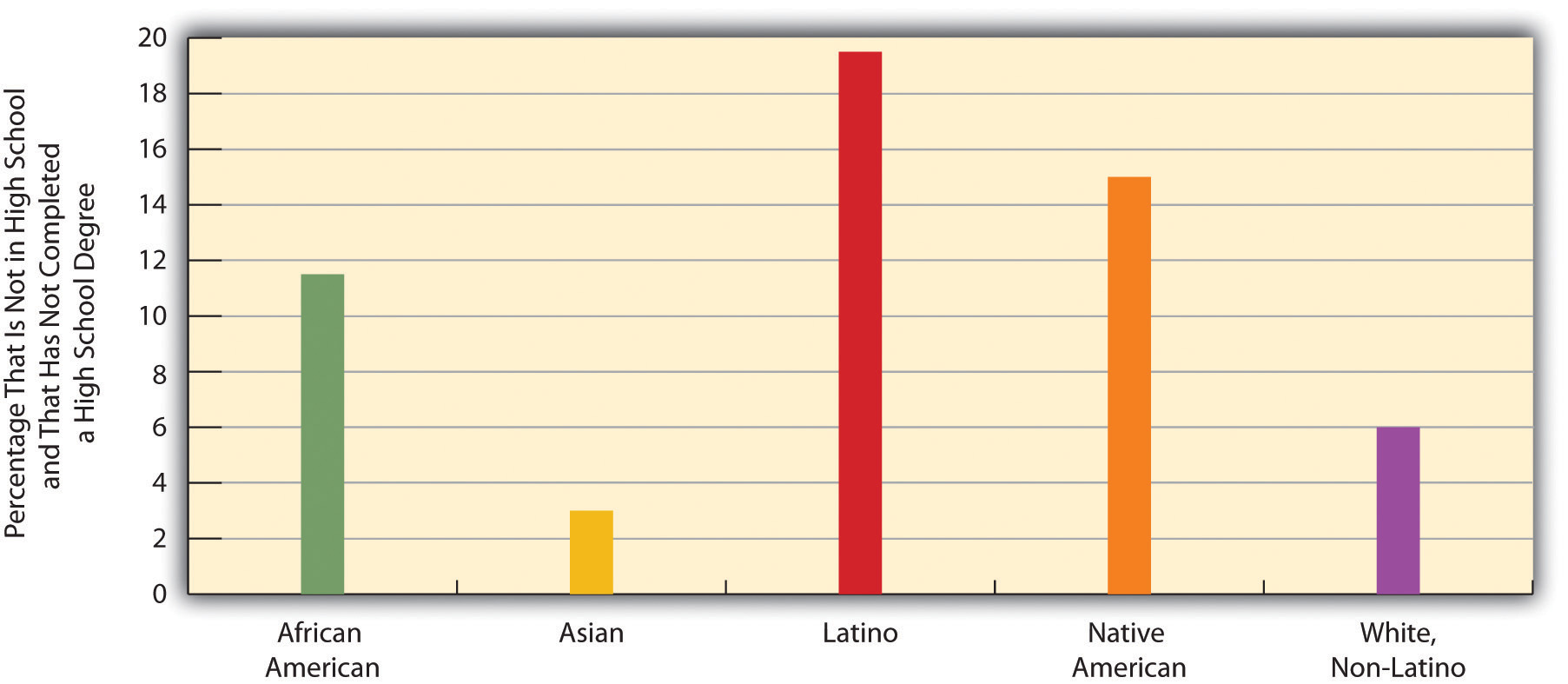

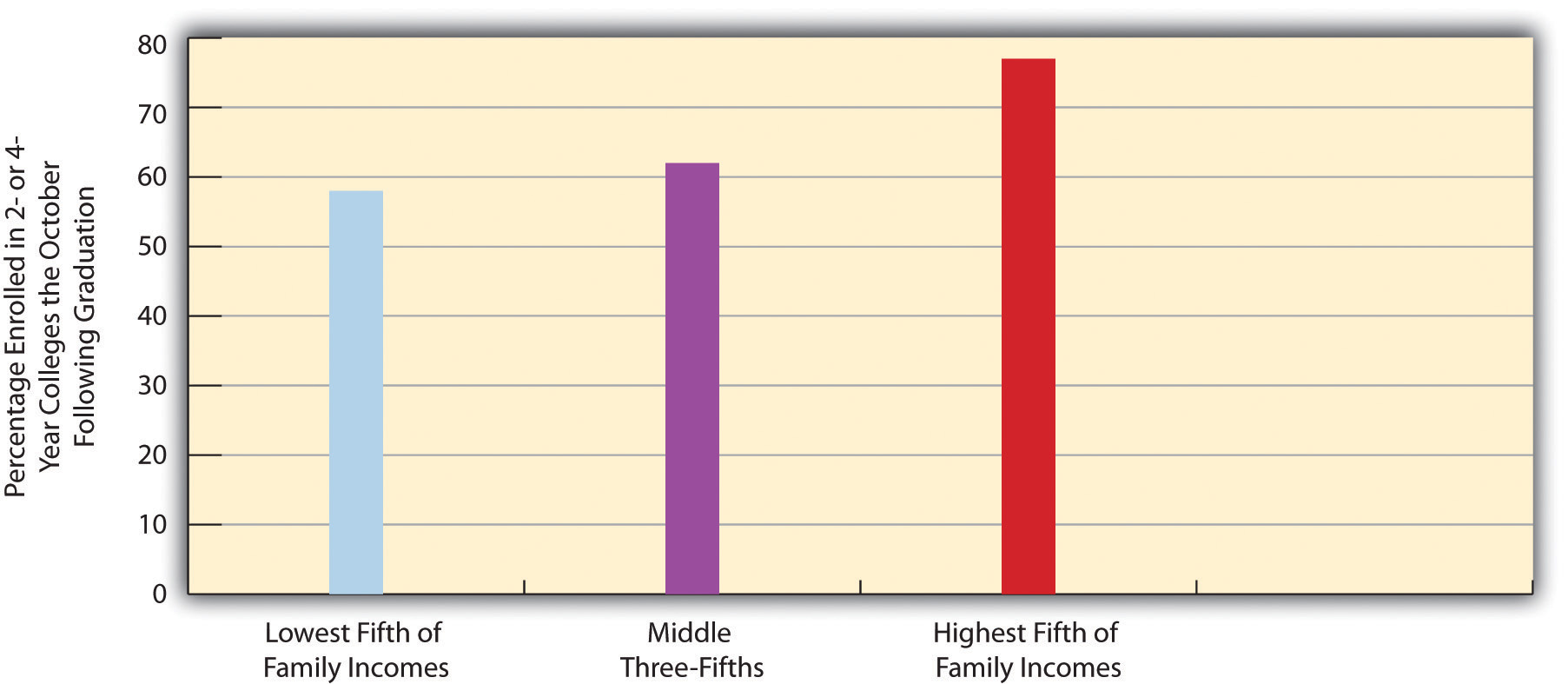

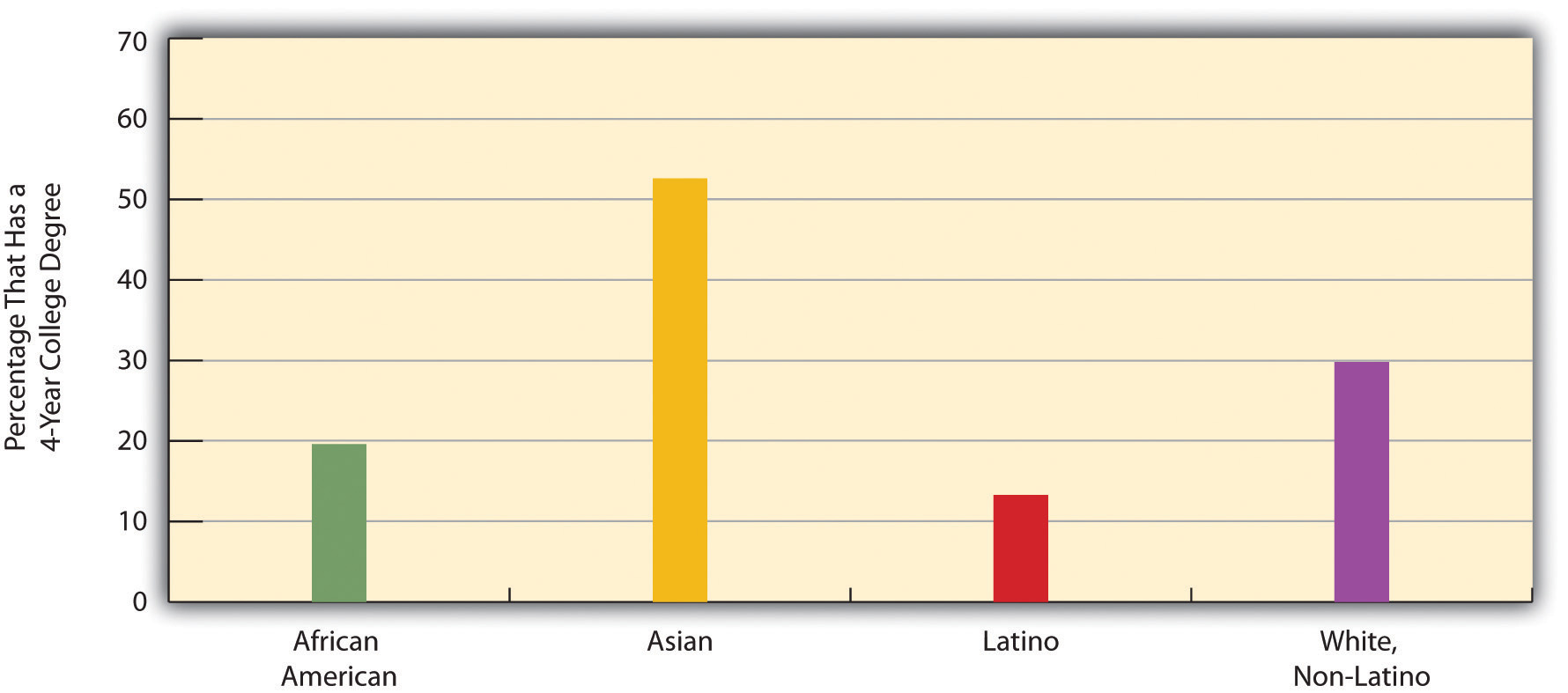

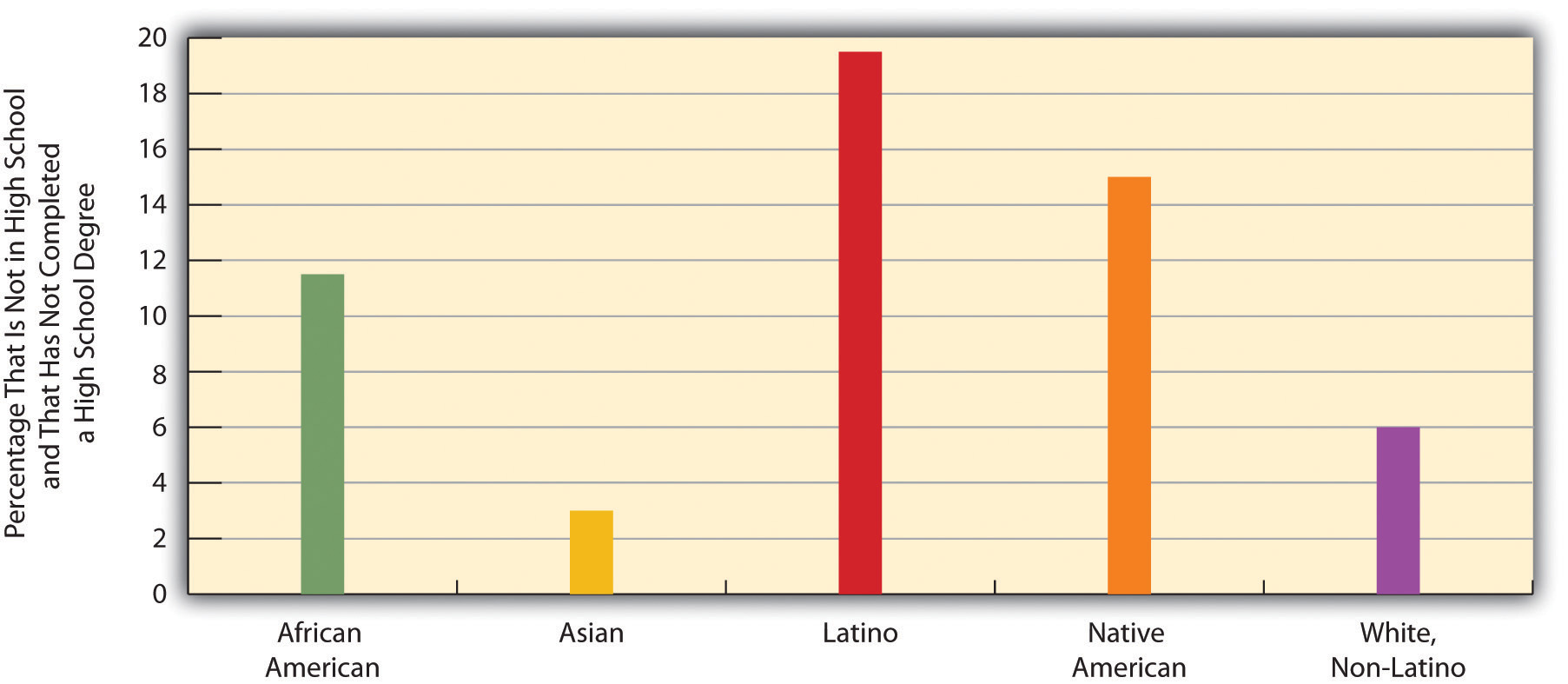

The figure below "Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, 16–24-Year-Olds, 2007" shows how race and ethnicity affect dropping out of high school. The dropout rate is highest for Latinos and Native Americans and lowest for Asians and whites. One way of illustrating how income and race/ethnicity affect the chances of achieving a college degree is to examine the percentage of high school graduates who enroll in college immediately following graduation. As the figure "Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately After Graduation, 2007" shows, students from families in the highest income bracket are more likely than those in the lowest bracket to attend college. For race/ethnicity, it is useful to see the percentage of persons 25 or older who have at least a 4-year college degree. As the figure "Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons 25 or Older With a 4-Year College Degree, 2008" shows, this percentage varies significantly, with African Americans and Latinos least likely to have a degree.

Figure: Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, 16–24-Year-Olds, 2007

Figure: Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately After Graduation, 2007

Figure: Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons 25 or Older With a 4-Year College Degree, 2008

Why do African Americans and Latinos have lower educational attainment? Two factors are commonly cited: (a) the underfunded and otherwise inadequate schools that children in both groups often attend and (b) the higher poverty of their families and lower education of their parents that often leave them ill-prepared for school even before they enter kindergarten (Ballantine & Hammack, 2009; Yeung & Pfeiffer, 2009).

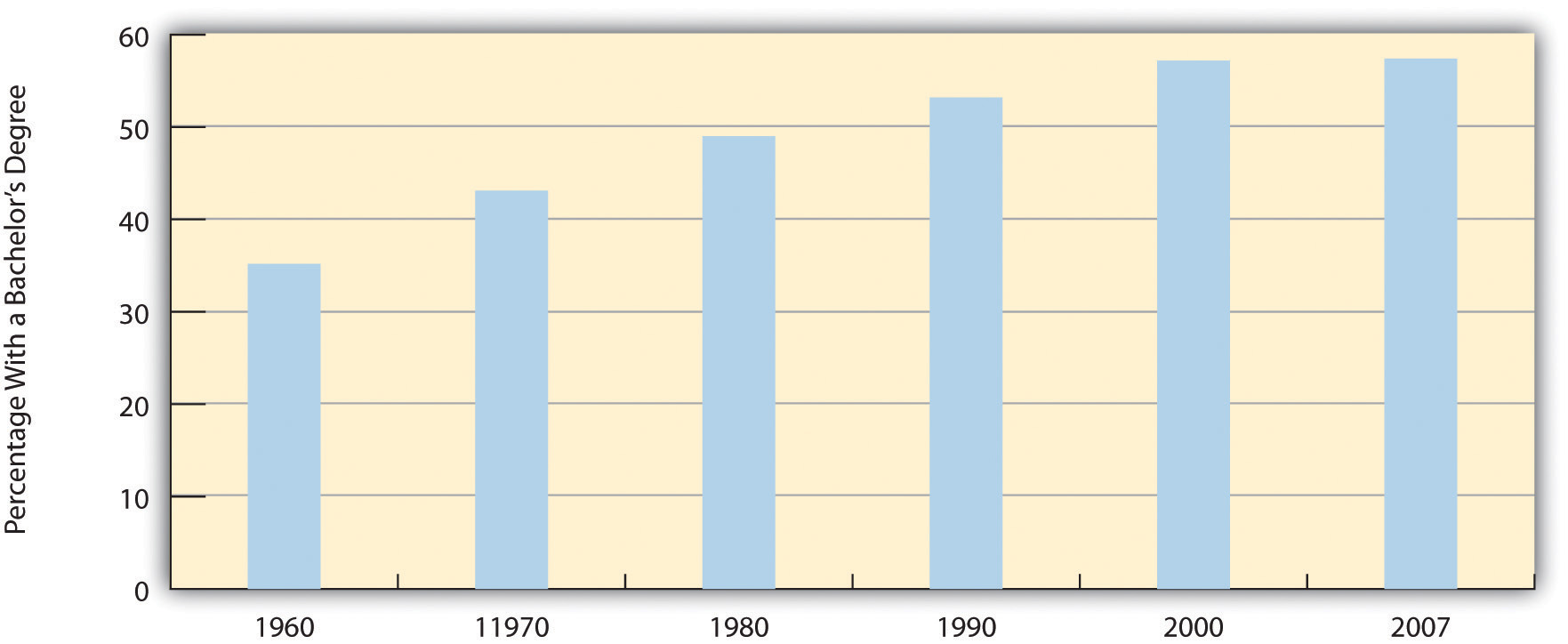

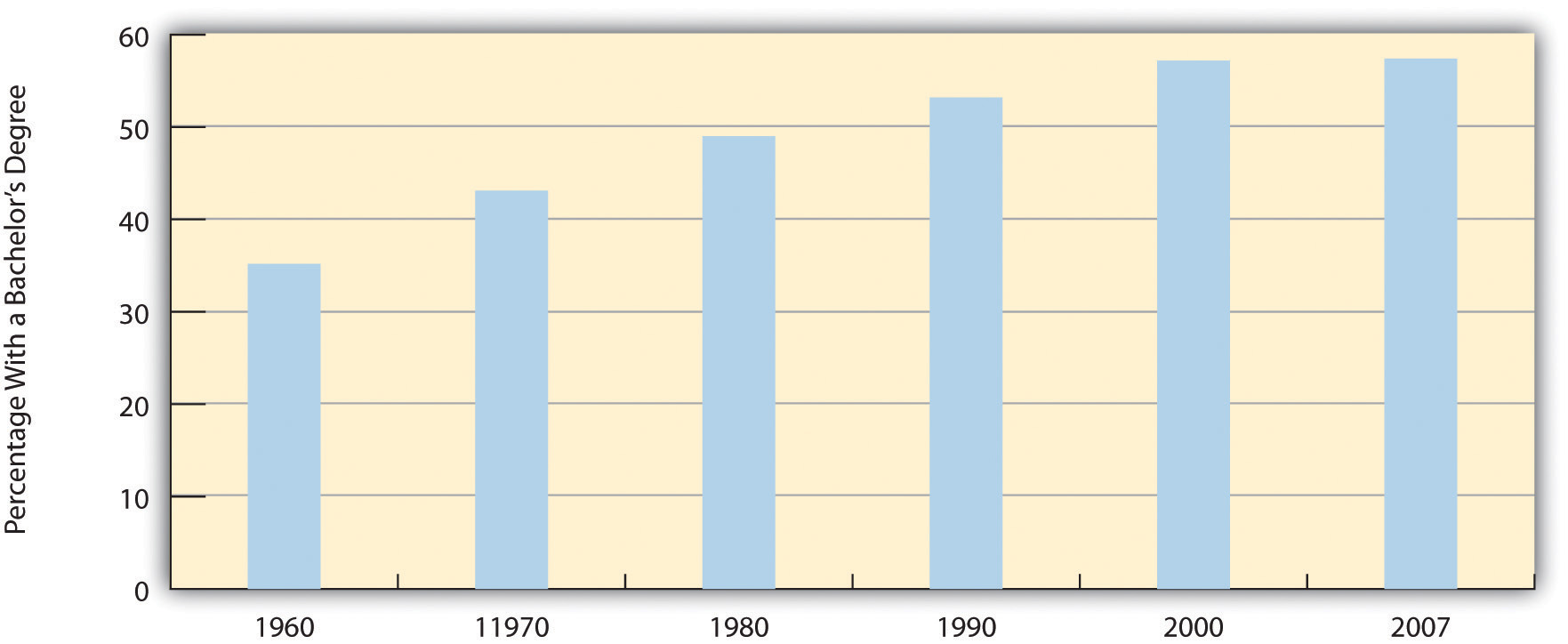

Does gender affect educational attainment? The answer is yes, but perhaps not in the way you expect. If we do not take age into account, slightly more men than women have a college degree: 30.1% of men and 28.8% of women. This difference reflects the fact that women were less likely than men in earlier generations to go to college. But now there is a gender difference in the other direction: women now earn more than 57% of all bachelor’s degrees, up from just 35% in 1960 (see the figure "Percentage of All Bachelor’s Degrees Received by Women, 1960–2007".)

Figure: Percentage of All Bachelor’s Degrees Received by Women, 1960–2007

The Difference Education Makes: Income

Have you ever applied for a job that required a high school degree? Are you going to college in part because you realize you will need a college degree for a higher-paying job? As these questions imply, the United States is a credential society (Collins, 1979). This means at least two things. First, a high school or college degree (or beyond) indicates that a person has acquired the needed knowledge and skills for various jobs. Second, a degree at some level is a requirement for most jobs. As you know full well, a college degree today is a virtual requirement for a decent-paying job. Over the years the ante has been upped considerably, as in earlier generations a high school degree, if even that, was all that was needed, if only because so few people graduated from high school to begin with (see figure "Percentage of Population 25 or Older With at Least a High School Degree, 1910–2008"). With so many people graduating from high school today, a high school degree is not worth as much. Then, too, today’s technological and knowledge-based postindustrial society increasingly requires skills and knowledge that only a college education brings.

Figure: Percentage of Population 25 or Older With at Least a High School Degree, 1910–2008

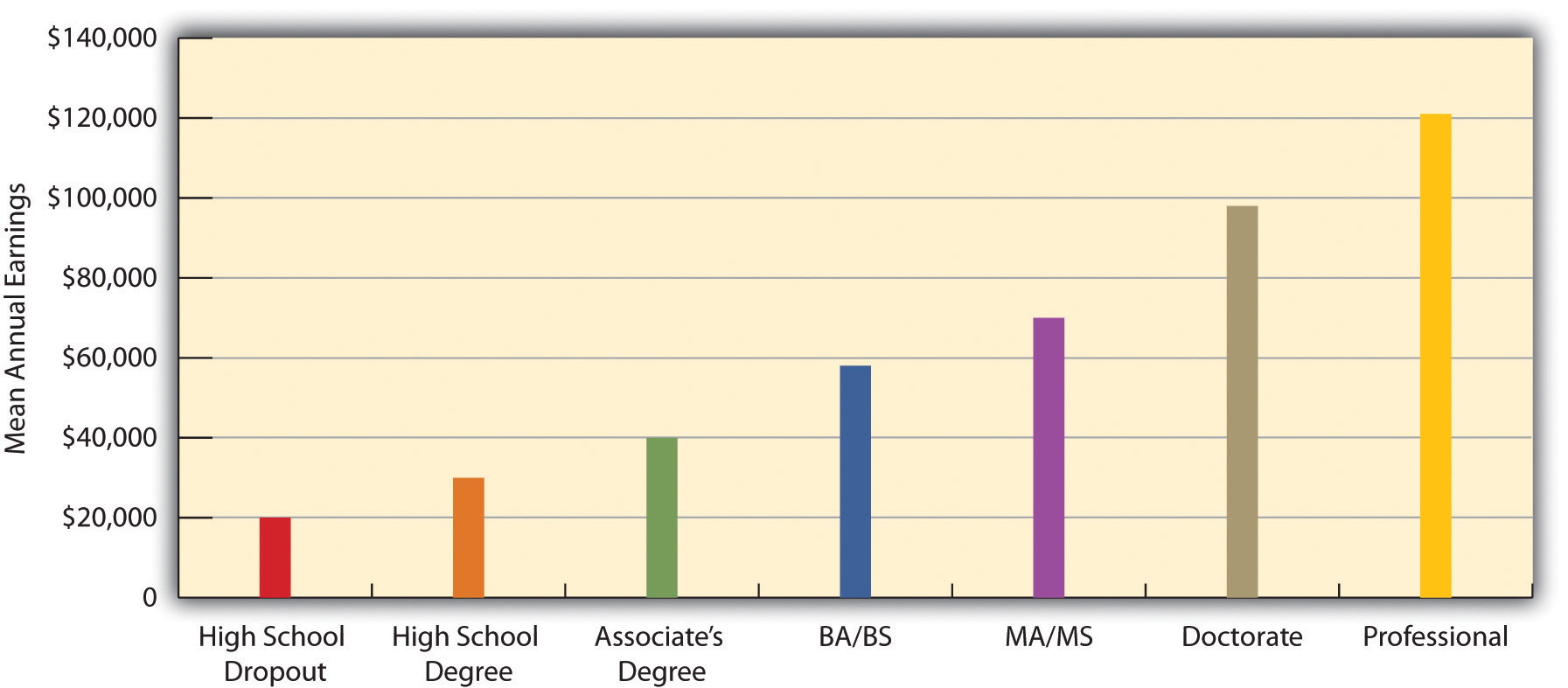

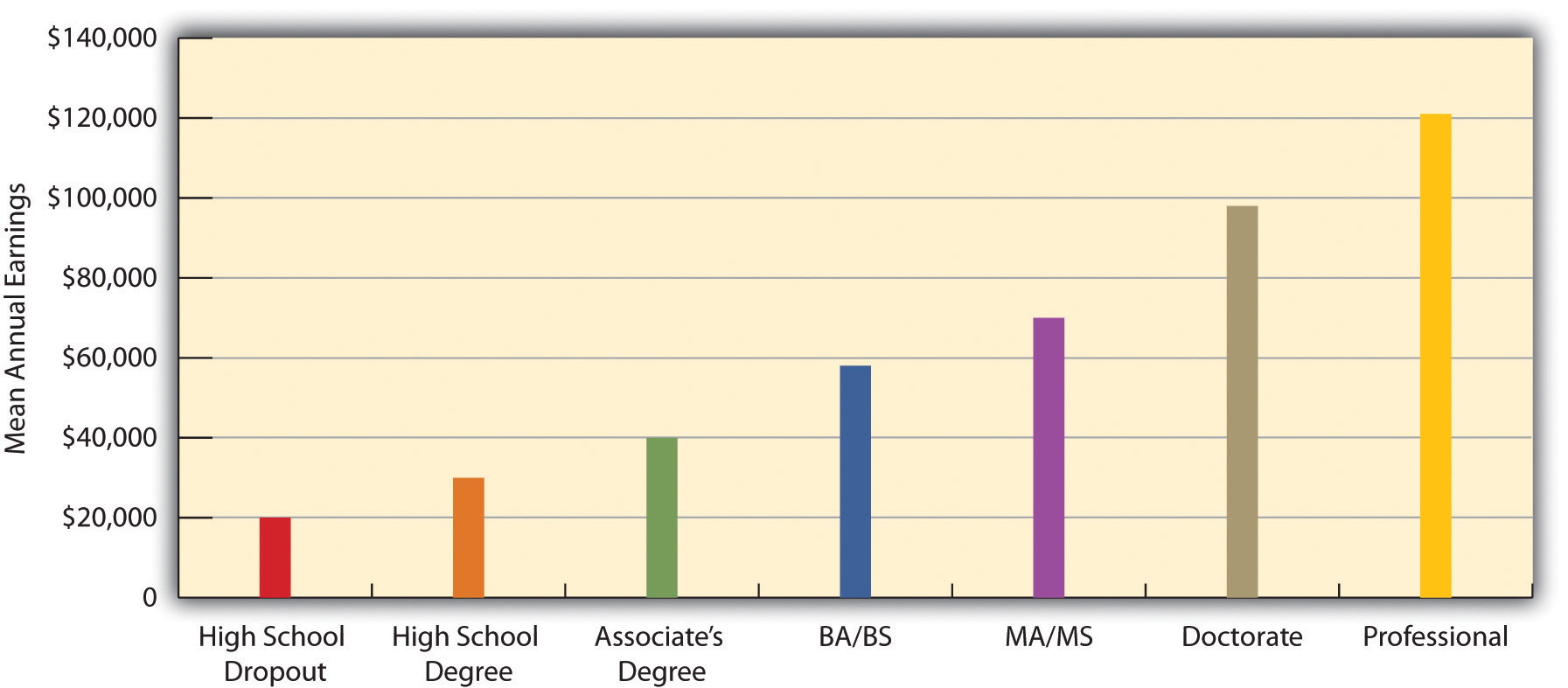

A credential society also means that people with more educational attainment achieve higher incomes. Annual earnings are indeed much higher for people with more education (see figure "Educational Attainment and Mean Annual Earnings, 2007"). As earlier chapters indicated, gender and race/ethnicity affect the payoff we get from our education, but education itself still makes a huge difference for our incomes.

On the average, college graduates have much higher annual earnings than high school graduates. How much does this consequence affect why you decided to go to college?

Figure: Educational Attainment and Mean Annual Earnings, 2007

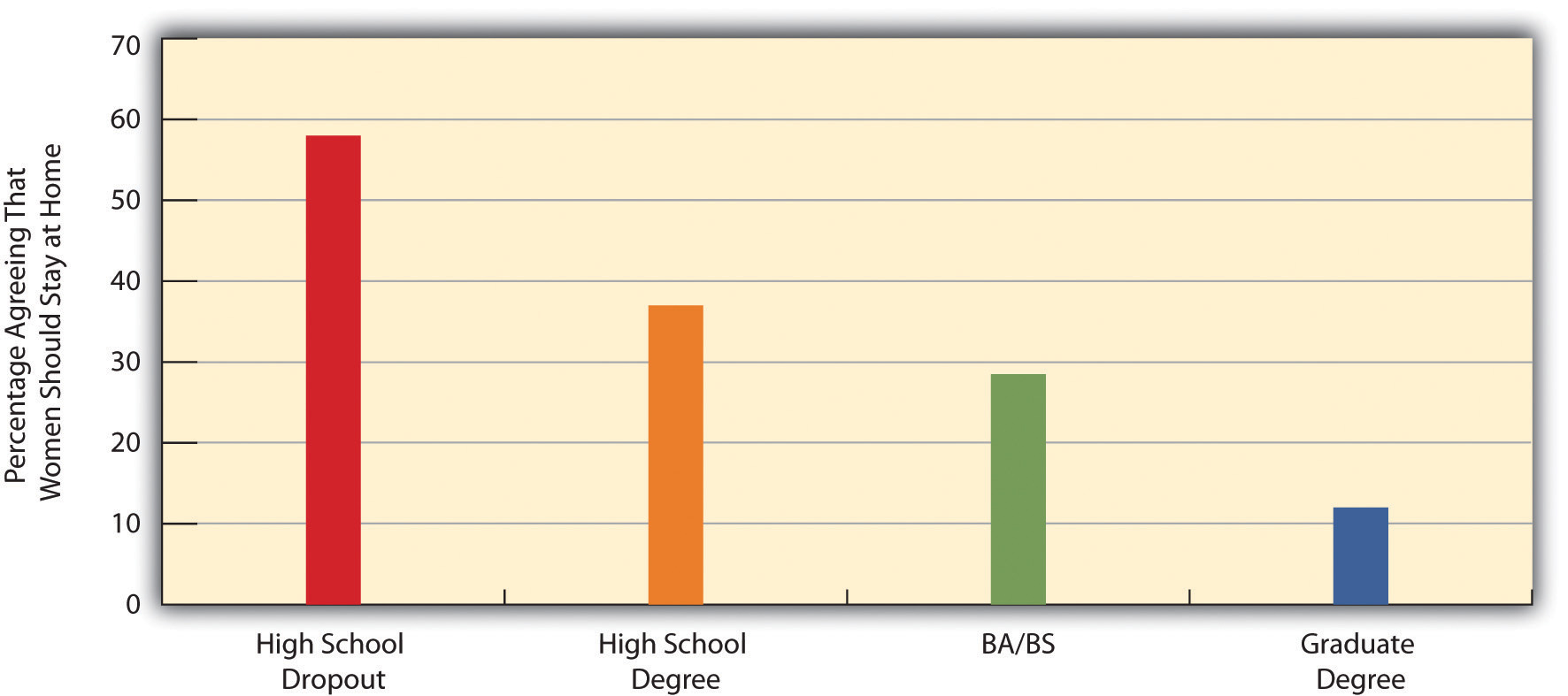

The Difference Education Makes: Attitudes

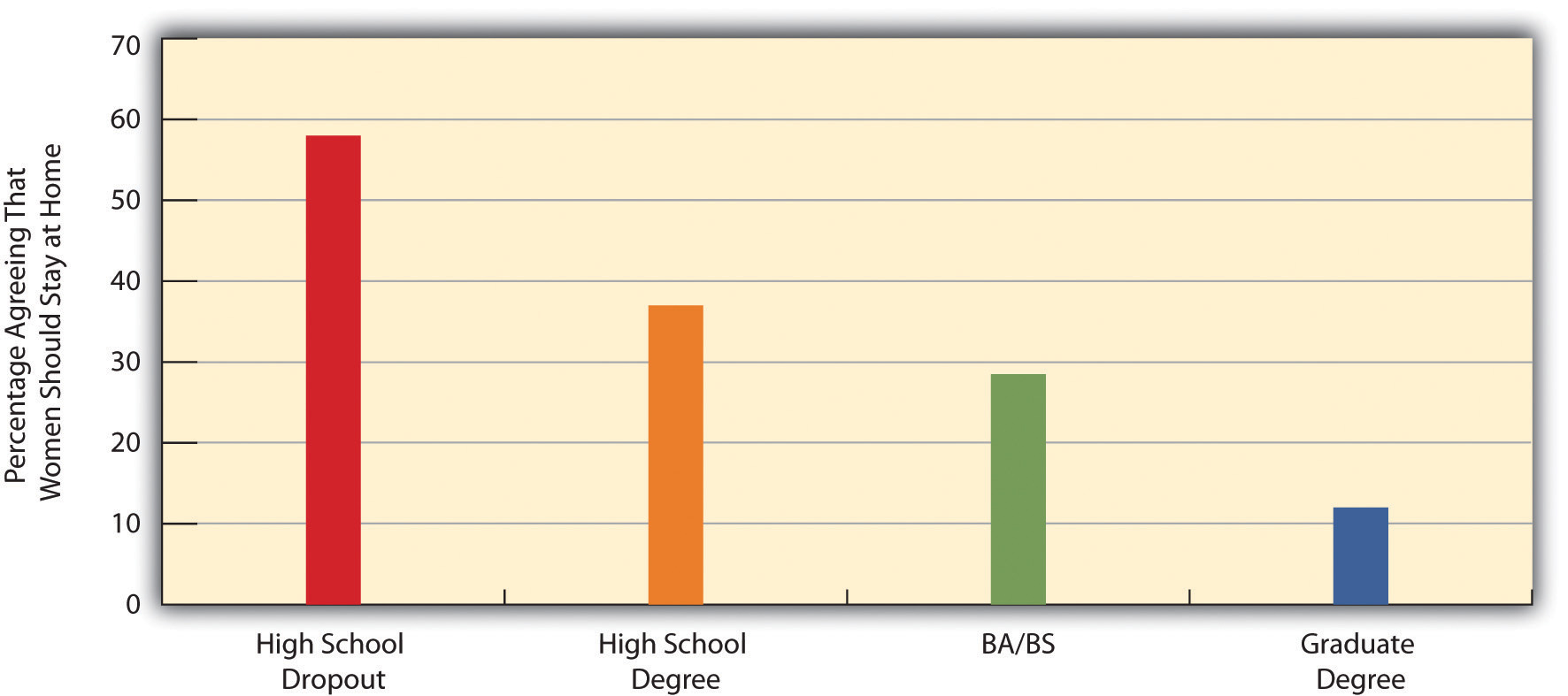

Education also makes a difference for our attitudes. Researchers use different strategies to determine this effect. They compare adults with different levels of education; they compare college seniors with first-year college students; and sometimes they even study a group of students when they begin college and again when they are about to graduate. However they do so, they typically find that education leads us to be more tolerant and even approving of nontraditional beliefs and behaviors and less likely to hold various kinds of prejudices (McClelland & Linnander, 2006; Moore & Ovadia, 2006). Racial prejudice and sexism, two types of belief explored in previous chapters, all reduce with education. Education has these effects because the material we learn in classes and the experiences we undergo with greater schooling all teach us new things and challenge traditional ways of thinking and acting.

We see evidence of education’s effect in figure "Education and Agreement That “It Is Much Better for Everyone Involved If the Man Is the Achiever Outside the Home and the Woman Takes Care of the Home and Family”", which depicts the relationship in the General Social Survey between education and agreement with the statement that “it is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” College-educated respondents are much less likely than those without a high school degree to agree with this statement.

Figure: Education and Agreement That “It Is Much Better for Everyone Involved If the Man Is the Achiever Outside the Home and the Woman Takes Care of the Home and Family”

As two of our most important social institutions, the family and education arouse considerable and often heated debate over their status and prospects. Opponents in these debates all care passionately about families and/or schools but often take diametrically opposed views on the causes of these institutions’ problems and possible solutions to the issues they face. A sociological perspective on the family and education emphasizes the social inequalities that lie at the heart of many of these issues, and it stresses that these two institutions reinforce and contribute to social inequalities.

Accordingly, efforts to address family and education issues should include the following strategies and policies, some of which were included in the previous section on reducing social inequality: (a) increasing financial support, vocational training, and financial aid for schooling for women who wish to return to the labor force or to increase their wages; (b) establishing and strengthening early childhood visitation programs and nutrition and medical care assistance for poor women and their children; (c) reducing the poverty and gender inequality that underlie much family violence; (d) allowing for same-sex marriage; (e) strengthening efforts to help preserve marriage while proceeding cautiously or not at all for marriages that are highly contentious; (f) increasing funding so that schools can be smaller, better equipped, and in decent repair; and (g) strengthening antibullying programs and other efforts to reduce intimidation and violence within the schools.

10 WAYS SCHOOL HAS CHANGED…

The following is an excerpt from What She Said published AUGUST 5, 2016. It’s less than a year since I wrote lamenting the empty space in our new building, while teachers kept their doors shut and the learning inside their own rooms. Walking through ‘the space’ these days, as we approach the end of the school year, I’m struck by how much has changed.

There are groups of kids everywhere, sprawled on the floor, huddled on the steps, sitting around tables, even standing on chairs so that they can film from above! They are collaborating on inquiries, creating presentations, making movies and expressing their learning in all kinds of creative ways. It’s active and social, noisy and messy… as learning should be.

School has changed…

1. We used to imprison the learning inside the classrooms… Now the whole school is our learning environment.

2. We used to find information in books and on the internet… Now we also interact globally via Skype with primary sources.

3. We used to control everything… Now students take ownership of their learning.

4. We used to think ‘computer’ was a lesson in the lab… Now technology is an integral part of learning across the curriculum.

5. We used to collect students’ work, to read and mark it… Now they create content for an authentic global audience.

6. We used to strive for quiet in the classroom… Now the school is filled with vibrant and noisy engagement in learning.

7. We used to teach everything we wanted students to know… Now we know learning can take place through student centred inquiry.

8. We used to set tests to check mastery of a topic… Now learning is often assessed through what students create.

9. We used to plan differentiated tasks, depending on ability… Now digital tools provide opportunities for natural differentiation.

10. We used to have an award ceremony for the graduating Year 6 students… Now every child will be acknowledged at graduation.

Not every point is uniformly evident across the school irrespective of teacher, class and time (yet), but most are well on the way. Learning in our school has changed enormously… and is constantly changing. Is yours?

“What the educator does in teaching is to make it possible for the students to become themselves” (Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed). David Simon, in his book Social Problems and the Sociological Imagination: A Paradigm for Analysis (1995), points to the notion that social problems are, in essence, contradictions—that is, statements, ideas, or features of a situation that are opposed to one another. Consider then, that one of the greatest expectations in U.S. society is that to attain any form of success in life, a person needs an education. In fact, a college degree is rapidly becoming an expectation at nearly all levels of middle-class success, not merely an enhancement to our occupational choices. And, as you might expect, the number of people graduating from college in the United States continues to rise dramatically.

The contradiction, however, lies in the fact that the more necessary a college degree has become, the harder it has become to achieve it. The cost of getting a college degree has risen sharply since the mid-1980s, while government support in the form of Pell Grants has barely increased. The net result is that those who do graduate from college are likely to begin a career in debt. As of 2013, the average of amount of a typical student’s loans amounted to around $29,000. Added to that is that employment opportunities have not met expectations. The Washington Post (Brad Plumer May 20, 2013) notes that in 2010, only 27 percent of college graduates had a job related to their major. The business publication Bloomberg News states that among twenty-two-year-old degree holders who found jobs in the past three years, more than half were in roles not even requiring a college diploma (Janet Lorin and Jeanna Smialek, June 5, 2014).

Is a college degree still worth it? All this is not to say that lifetime earnings among those with a college degree are not, on average, still much higher than for those without. But even with unemployment among degree-earners at a low of 3 percent, the increase in wages over the past decade has remained at a flat 1 percent. And the pay gap between those with a degree and those without has continued to increase because wages for the rest have fallen (David Leonhardt, New York Times, The Upshot, May 27, 2014).

But is college worth more than money?

Generally, the first two years of college are essentially a liberal arts experience. The student is exposed to a fairly broad range of topics, from mathematics and the physical sciences to history and literature, the social sciences, and music and art through introductory and survey-styled courses. It is in this period that the student’s world view is, it is hoped, expanded. Memorization of raw data still occurs, but if the system works, the student now looks at a larger world. Then, when he or she begins the process of specialization, it is with a much broader perspective than might be otherwise. This additional “cultural capital” can further enrich the life of the student, enhance his or her ability to work with experienced professionals, and build wisdom upon knowledge. Two thousand years ago, Socrates said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” The real value of an education, then, is to enhance our skill at self-examination.

References

Leonhardt, David. 2014. “Is College Worth It? Clearly , New Data Say.” The New York Times. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

Lorin Janet, and Jeanna Smialek. 2014. “College Graduates Struggle to Find Eployment Worth a Degree.” Bloomberg. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

New Oxford English Dictionary. “contradiction.” New Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

Plumer, Brad. 2013. “Only 27 percent of college graduates have a job related ot their major.” The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

Simon, R David. 1995. Social Problems and the Sociological Imagination: A Paradigm for Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Education in the United States is a massive social institution involving millions of people and billions of dollars. About 75 million people, almost one-fourth of the U.S. population, attend school at all levels. This number includes 40 million in grades pre-K through 8, 16 million in high school, and 19 million in college (including graduate and professional school). They attend some 132,000 elementary and secondary schools and about 4,200 2-year and 4-year colleges and universities and are taught by about 4.8 million teachers and professors (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab Education is a huge social institution.

Correlates of Educational Attainment

About 65% of U.S. high school graduates enroll in college the following fall. This is a very high figure by international standards, as college in many other industrial nations is reserved for the very small percentage of the population who pass rigorous entrance exams. They are the best of the brightest in their nations, whereas higher education in the United States is open to all who graduate high school. Even though that is true, our chances of achieving a college degree are greatly determined at birth, as social class and race/ethnicity have a significant effect on access to college. They affect whether students drop out of high school, in which case they do not go on to college; they affect the chances of getting good grades in school and good scores on college entrance exams; they affect whether a family can afford to send its children to college; and they affect the chances of staying in college and obtaining a degree versus dropping out. For these reasons, educational attainment depends heavily on family income and race and ethnicity.

The figure below "Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, 16–24-Year-Olds, 2007" shows how race and ethnicity affect dropping out of high school. The dropout rate is highest for Latinos and Native Americans and lowest for Asians and whites. One way of illustrating how income and race/ethnicity affect the chances of achieving a college degree is to examine the percentage of high school graduates who enroll in college immediately following graduation. As the figure "Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately After Graduation, 2007" shows, students from families in the highest income bracket are more likely than those in the lowest bracket to attend college. For race/ethnicity, it is useful to see the percentage of persons 25 or older who have at least a 4-year college degree. As the figure "Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons 25 or Older With a 4-Year College Degree, 2008" shows, this percentage varies significantly, with African Americans and Latinos least likely to have a degree.

Figure: Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, 16–24-Year-Olds, 2007

Figure: Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately After Graduation, 2007

Figure: Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons 25 or Older With a 4-Year College Degree, 2008

Why do African Americans and Latinos have lower educational attainment? Two factors are commonly cited: (a) the underfunded and otherwise inadequate schools that children in both groups often attend and (b) the higher poverty of their families and lower education of their parents that often leave them ill-prepared for school even before they enter kindergarten (Ballantine & Hammack, 2009; Yeung & Pfeiffer, 2009).

Does gender affect educational attainment? The answer is yes, but perhaps not in the way you expect. If we do not take age into account, slightly more men than women have a college degree: 30.1% of men and 28.8% of women. This difference reflects the fact that women were less likely than men in earlier generations to go to college. But now there is a gender difference in the other direction: women now earn more than 57% of all bachelor’s degrees, up from just 35% in 1960 (see the figure "Percentage of All Bachelor’s Degrees Received by Women, 1960–2007".)

Figure: Percentage of All Bachelor’s Degrees Received by Women, 1960–2007

The Difference Education Makes: Income

Have you ever applied for a job that required a high school degree? Are you going to college in part because you realize you will need a college degree for a higher-paying job? As these questions imply, the United States is a credential society (Collins, 1979). This means at least two things. First, a high school or college degree (or beyond) indicates that a person has acquired the needed knowledge and skills for various jobs. Second, a degree at some level is a requirement for most jobs. As you know full well, a college degree today is a virtual requirement for a decent-paying job. Over the years the ante has been upped considerably, as in earlier generations a high school degree, if even that, was all that was needed, if only because so few people graduated from high school to begin with (see figure "Percentage of Population 25 or Older With at Least a High School Degree, 1910–2008"). With so many people graduating from high school today, a high school degree is not worth as much. Then, too, today’s technological and knowledge-based postindustrial society increasingly requires skills and knowledge that only a college education brings.

Figure: Percentage of Population 25 or Older With at Least a High School Degree, 1910–2008

A credential society also means that people with more educational attainment achieve higher incomes. Annual earnings are indeed much higher for people with more education (see figure "Educational Attainment and Mean Annual Earnings, 2007"). As earlier chapters indicated, gender and race/ethnicity affect the payoff we get from our education, but education itself still makes a huge difference for our incomes.

On the average, college graduates have much higher annual earnings than high school graduates. How much does this consequence affect why you decided to go to college?

Figure: Educational Attainment and Mean Annual Earnings, 2007

The Difference Education Makes: Attitudes

Education also makes a difference for our attitudes. Researchers use different strategies to determine this effect. They compare adults with different levels of education; they compare college seniors with first-year college students; and sometimes they even study a group of students when they begin college and again when they are about to graduate. However they do so, they typically find that education leads us to be more tolerant and even approving of nontraditional beliefs and behaviors and less likely to hold various kinds of prejudices (McClelland & Linnander, 2006; Moore & Ovadia, 2006). Racial prejudice and sexism, two types of belief explored in previous chapters, all reduce with education. Education has these effects because the material we learn in classes and the experiences we undergo with greater schooling all teach us new things and challenge traditional ways of thinking and acting.

We see evidence of education’s effect in figure "Education and Agreement That “It Is Much Better for Everyone Involved If the Man Is the Achiever Outside the Home and the Woman Takes Care of the Home and Family”", which depicts the relationship in the General Social Survey between education and agreement with the statement that “it is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” College-educated respondents are much less likely than those without a high school degree to agree with this statement.

Figure: Education and Agreement That “It Is Much Better for Everyone Involved If the Man Is the Achiever Outside the Home and the Woman Takes Care of the Home and Family”

As two of our most important social institutions, the family and education arouse considerable and often heated debate over their status and prospects. Opponents in these debates all care passionately about families and/or schools but often take diametrically opposed views on the causes of these institutions’ problems and possible solutions to the issues they face. A sociological perspective on the family and education emphasizes the social inequalities that lie at the heart of many of these issues, and it stresses that these two institutions reinforce and contribute to social inequalities.

Accordingly, efforts to address family and education issues should include the following strategies and policies, some of which were included in the previous section on reducing social inequality: (a) increasing financial support, vocational training, and financial aid for schooling for women who wish to return to the labor force or to increase their wages; (b) establishing and strengthening early childhood visitation programs and nutrition and medical care assistance for poor women and their children; (c) reducing the poverty and gender inequality that underlie much family violence; (d) allowing for same-sex marriage; (e) strengthening efforts to help preserve marriage while proceeding cautiously or not at all for marriages that are highly contentious; (f) increasing funding so that schools can be smaller, better equipped, and in decent repair; and (g) strengthening antibullying programs and other efforts to reduce intimidation and violence within the schools.

10 WAYS SCHOOL HAS CHANGED…

The following is an excerpt from What She Said published AUGUST 5, 2016. It’s less than a year since I wrote lamenting the empty space in our new building, while teachers kept their doors shut and the learning inside their own rooms. Walking through ‘the space’ these days, as we approach the end of the school year, I’m struck by how much has changed.

There are groups of kids everywhere, sprawled on the floor, huddled on the steps, sitting around tables, even standing on chairs so that they can film from above! They are collaborating on inquiries, creating presentations, making movies and expressing their learning in all kinds of creative ways. It’s active and social, noisy and messy… as learning should be.

School has changed…

1. We used to imprison the learning inside the classrooms… Now the whole school is our learning environment.

2. We used to find information in books and on the internet… Now we also interact globally via Skype with primary sources.

3. We used to control everything… Now students take ownership of their learning.

4. We used to think ‘computer’ was a lesson in the lab… Now technology is an integral part of learning across the curriculum.

5. We used to collect students’ work, to read and mark it… Now they create content for an authentic global audience.

6. We used to strive for quiet in the classroom… Now the school is filled with vibrant and noisy engagement in learning.

7. We used to teach everything we wanted students to know… Now we know learning can take place through student centred inquiry.

8. We used to set tests to check mastery of a topic… Now learning is often assessed through what students create.

9. We used to plan differentiated tasks, depending on ability… Now digital tools provide opportunities for natural differentiation.

10. We used to have an award ceremony for the graduating Year 6 students… Now every child will be acknowledged at graduation.

Not every point is uniformly evident across the school irrespective of teacher, class and time (yet), but most are well on the way. Learning in our school has changed enormously… and is constantly changing. Is yours?

"The student who sets out with such a spirit of perseverance will surely find success and realization at last."

- Swami Vivekananda

There is much more that occurs in a classroom beyond the acquisition of academic knowledge. In this topic we will focus on social issues which affect student learning, teaching style decisions, classroom management techniques and ultimately the way you create professional student-teacher relationships. While it may seem as if these situations 'won't happen in my class' rest assured they most certainly will - the question is whether or not you'll realize it.

"The student who sets out with such a spirit of perseverance will surely find success and realization at last."

- Swami Vivekananda

There is much more that occurs in a classroom beyond the acquisition of academic knowledge. In this topic we will focus on social issues which affect student learning, teaching style decisions, classroom management techniques and ultimately the way you create professional student-teacher relationships. While it may seem as if these situations 'won't happen in my class' rest assured they most certainly will - the question is whether or not you'll realize it.

- Discuss the reality of student dropout rates and possible preventative measures

- Identify best practices for managing students who attempt to cheat or may be tempted to cheat

- Discuss the reality and management of school violence and student aggression

- Discuss how bullying, drug & alcohol abuse, suicide, teen pregnancy, child abuse, homelessness and poverty can affect classroom behavior and ability to learn

- Today's family compositions are unique, identify and discuss challenges for single, divorcing, same-sex, two-working parent and other family situations that affect students

- Become familiar with terms such as self-monitoring, self-perception, cognitive dissonance, socioeconomic status (SES), generational poverty and cyber bullying

- Discuss the reality of student dropout rates and possible preventative measures

- Identify best practices for managing students who attempt to cheat or may be tempted to cheat

- Discuss the reality and management of school violence and student aggression

- Discuss how bullying, drug & alcohol abuse, suicide, teen pregnancy, child abuse, homelessness and poverty can affect classroom behavior and ability to learn

- Today's family compositions are unique, identify and discuss challenges for single, divorcing, same-sex, two-working parent and other family situations that affect students

- Become familiar with terms such as self-monitoring, self-perception, cognitive dissonance, socioeconomic status (SES), generational poverty and cyber bullying