12 Classroom Environment

Unlearning Box

Joey comes to school in the morning, and one of his classmates makes a negative comment about his shirt. It’s already been a rough morning–he accidentally overslept his alarm and his grandma was yelling at him to hurry up so he wouldn’t be late–so he snaps at his classmate, “Oh shut up.” His teacher overhears and says, “We don’t use that language at school, so now your card is on yellow.” He tries to explain: “But he–” but his teacher interrupts. “Oh, now you’re talking back to me? That’s a red card and now you have silent lunch.”

Joey was having a rough morning, and the classroom environment didn’t help him at all. In this example, you can see how some traditional approaches to behavior management–including card-flipping systems and silent lunch–don’t get to the root of the problem and actually can cause more harm, making them ineffective practices.

In this chapter, we will investigate the elements of classroom environment, how trauma impacts classroom environments, critical community stakeholders in classroom environments, and strategies for building a positive classroom environment.

Chapter Outline

Elements of Classroom Environment

In order for students to be successful at school, we must first carefully craft a supportive, learning-centered classroom environment. There are many aspects to consider when designing your classroom environment. Some are within your direct control as an educator, and others are not.

Three things you can control as you craft your own classroom environment are physical set-up, overall atmosphere, and behavior management. Together, you may hear these elements referred to as “classroom management.” The idea behind this term is that you have certain systems in your classroom that need to be “managed,” or organized, in order to scaffold your students’ success.

- Physical set-up: How are desks and tables arranged? Can all students easily see the Smartboard or dry erase board? Are there spaces for students to participate in whole-group, small-group, and individual learning? Are learning materials (including math manipulatives, paper, pencils, science notebooks, and books for reading) easily accessible and organized?

- Overall atmosphere: Does the classroom feel structured, warm, and welcoming, or does it feel cold, sterile, and depersonalized? Does the teacher interact with students in positive ways that build their trust, or does the teacher yell at students and talk down to them? Do students feel like this is a “home” for them and their learning, or do they count down the hours each day until they can leave?

- Behavior management: Are there clear expectations of acceptable behavior in the classroom? Are there clearly-established norms or policies, or is everyone unclear exactly what the “rules” are? Are there clear consequences or rewards for off- or on-task behavior? Are these rewards and consequences applied to all students equitably, or are some students in certain groups offered more rewards or more consequences compared with similar behaviors in their peers? Is there a communication system in place so educators, students, and families know these expectations and how the performance of their specific student measures up?

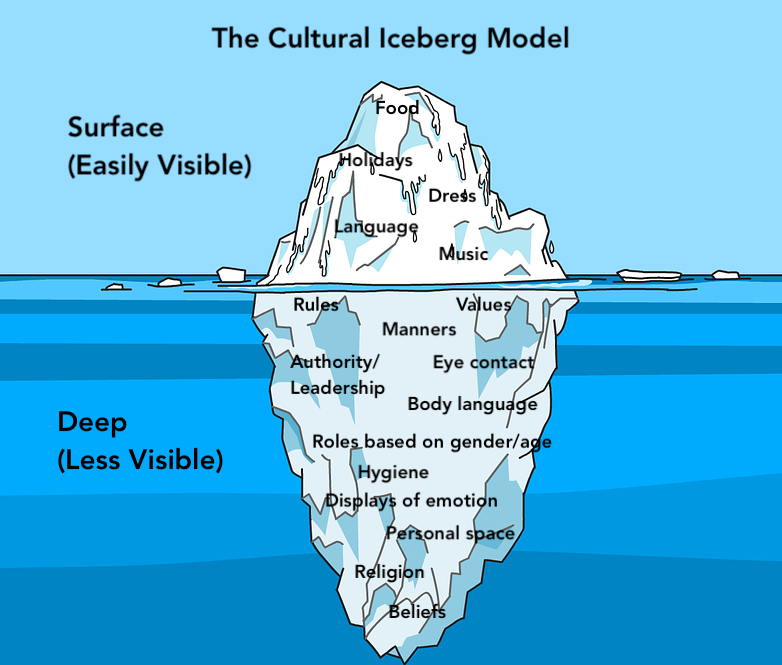

Some elements are beyond your control in your classroom, such as trauma students may have experienced previously, or what resources your families or community has access to or lacks. In addition, sometimes cultural differences manifest themselves as apparent “misbehavior.” For example, if an educator comes from a culture where young people should look their elders in the eyes to show respect, they may accidentally label “misbehavior” in students who come from cultures where avoiding eye contact is actually a sign of respect. You may hear of these characteristics as part of a metaphorical “cultural iceberg” (Figure 11.1). On the surface, you may see cultural elements like cuisine, holidays, or ways of dressing; however, even more lies below this “visible” surface, such as body language, concepts of fairness, and even expectations of what “good behavior” means.

Figure 11.1: The Cultural Iceberg Model

Trauma, resources, and culture, though not part of “classroom management,” still impact the overall classroom environment, and therefore are important to be aware of. For this reason, we intentionally refer to “classroom environment” throughout this chapter because we feel it is more inclusive of the many contexts and systems that impact your students’ learning success.

Critical Lens: Race and Classroom Management

While we like to think of our classrooms as fair, equitable places when it comes to classroom management, the reality is that this isn’t always true. Teachers of all races are more likely to punish Black students (Smith, 2015), and Black girls are seven times more likely to be suspended than White girls (Finley, 2017). Sometimes, getting in trouble at school is an entry point into the juvenile detention system, leading to what is known as the “school-to-prison pipeline.”[1] It is important for educators to be aware of these statistics and trends in order to proactively support all students’ success within the classroom and beyond.

Trauma in the Educational Setting

When you think of a classroom environment, you may first think of a warm, welcoming environment where all students can thrive. The reality is that trauma can have a very real impact on students’ participation in instruction and the classroom community. Sometimes this trauma happens outside of the classroom, like Adverse Childhood Experiences; sometimes this trauma happens inside the classroom, like bullying. Being aware of different ways our students experience trauma both within and beyond the classroom helps us create learning environments that meet the needs of our students.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Our students, like Joey, come to school each day wearing an invisible backpack, filled with all of the experiences they have had in life. Some of these invisible backpacks are light because our students’ experiences thus far have been loving, safe, and predictable. Unfortunately, too many of our students wear heavy backpacks full of experiences that have been frightening, unpredictable, and unsafe. These experiences can be characterized as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Childhood exposure to abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction may lead to increased social, emotional, and behavioral difficulties as well as decreased academic performance in the educational environment. Additionally, traditional means of interventions and support may not be successful in modifying behaviors for the long-term. Meeting the needs of our students impacted by adverse childhood experiences requires a shift in the educational setting to focus on the consistent development of healthy relationships between students and staff including the implementation of trauma-informed classrooms and interventions.

The relationship between early adverse experiences and later health outcomes can be impacted by a variety of factors, including resiliency, or the ability to bounce back from these experiences. The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University studies resilience in children and explains what it is in the video In Brief: What is Resilience?

Resilience can be fostered through protective factors including one strong, positive relationship with an adult. As educators, we have the opportunity to be a protective factor in our students’ lives through our understanding of adverse experiences, their impact on our students, and developing and utilizing empathy in the classroom.

ACEs in the Classroom

Our students’ invisible backpacks can be filled with experiences that weigh them down and impact their ability to function successfully in the educational environment. These can be single-episode experiences, such as a house fire or car accident, or the more complex experience of developmental traumas. Developmental traumas can include ongoing physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, physical and emotional neglect, and household dysfunction. Abuse is defined by a caregiver’s action, or failure to act, resulting in death, significant physical or emotional harm, or the exploitation of a child under the age of 18 (Child Welfare Information Gateway, n.d.). Physical neglect can include failure to consistently meet basic needs such as food and shelter, as well as providing a safe, clean environment. (Recall Maslow’s hierarchy of needs that you learned in previous chapters: our physiological needs, such as food and shelter, must be met before we can do other things, like learning.) Failure to provide adequate medical and dental care are also forms of neglect, though families without resources are subject to these issues and, as a result, children experience a lack of adequate care, beyond their families’ control. Emotional neglect involves the failure to meet or recognize a child’s emotional needs. Household dysfunction is the most common adverse childhood experience in childhood as many of the characteristics are often co-occurring. This category includes a variety of factors impacting caregivers such as divorce or separation, alcohol and/or substance abuse, mental health issues, domestic violence, and incarceration (Felitti et al., 1998).

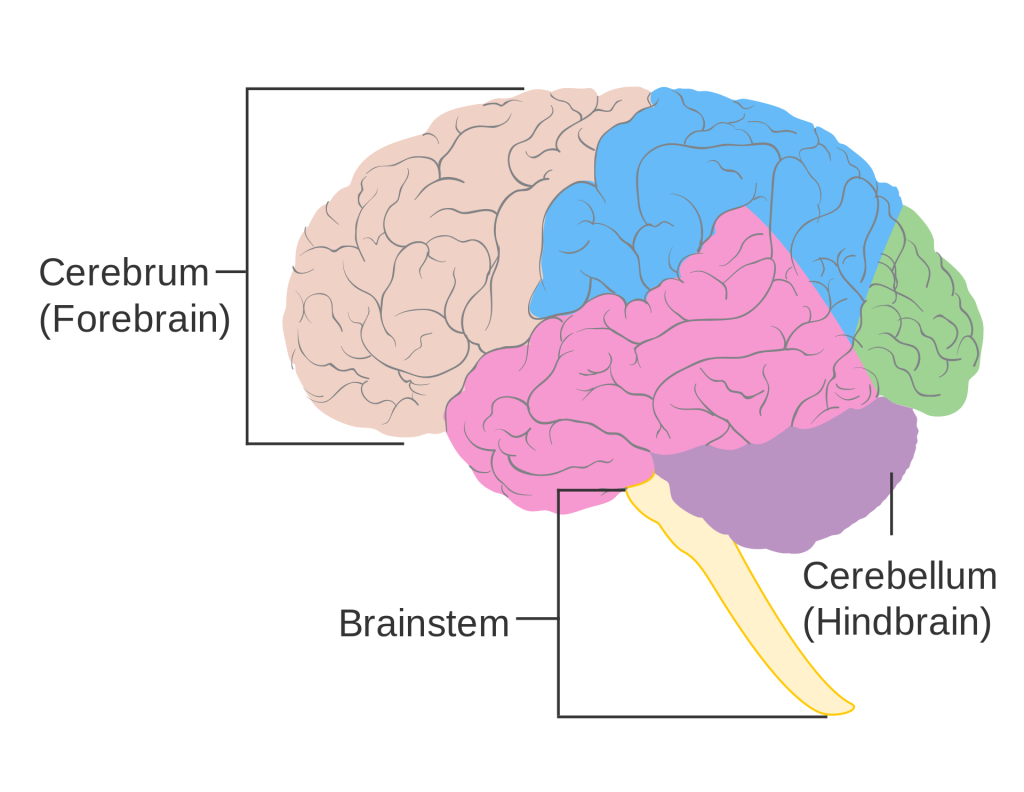

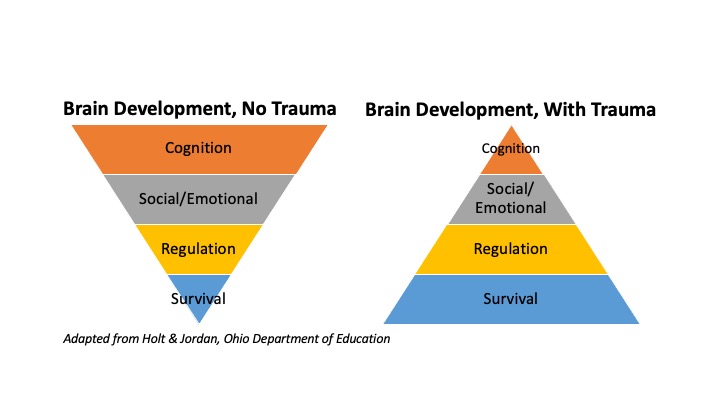

The dose-effect, or the frequency, severity, and duration of the experiences in our students’ lives can heavily impact their behavioral, social, emotional, and academic success. Bessel van der Kolk (2014) states the impact of chronic traumatic stress, the repetitive exposure to an experience overloading the body’s ability to cope, includes “pervasive biological and emotional dysregulation, failed or disrupted attachment, problems staying focused and on track, and a hugely deficient sense of coherent personal identity and competence” (p. 168). In essence, our students who experience chronic, traumatic stress can struggle to tolerate frustration and control their emotions, struggle to engage in healthy peer and adult relationships, as well as struggle to engage in executive functioning tasks such as initiating, sustaining, and completing work. This primarily occurs because trauma impacts their ability to access the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for these functions. The prefrontal cortex is part of the cerebrum. Instead, students with higher exposure to adverse childhood experiences tend to function more frequently in the brainstem, the part of the brain responsible for the autonomic responses of fight, flight, and freeze.

Figure 11.2 highlights the differences in brain functioning for a child who experienced typical early development and one who experienced developmental trauma. The areas of the brain responsible for cognition are far less active in students with developmental trauma while the part of the brain responsible for survival (i.e. fight, flight, or freeze) becomes the default response system.

Figure 11.2: Brain Development and Trauma

The fight, flight, or freeze response in the educational environment can inhibit our students’ ability to access their education effectively. It can also be disruptive to the learning of their peers. Some examples of fight, flight, or freeze responses include hitting, kicking, screaming, elopement (running away), pulling away from adults, not moving, hiding under furniture, shutting down, and withdrawing. It is important for us to remember these behaviors are coping skills that developed in response to stress or trauma the student was unable to manage any other way. Additionally, our student is not doing this to us. They are responding to a situation, internal or external, in which there is no other accessible way to cope. These situations are commonly referred to as triggers and may not always be predictable or observable for students with developmental trauma. For this reason, it is vital we develop policies and practices within the classroom which are trauma-informed as it will foster an environment in which empathy is present and healing can occur.

Bullying in the Classroom

While ACEs occur outside of the classroom setting, another element of trauma for students in school can be bullying. In 2017, about 20 percent of students ages 12–18 reported being bullied at school during the school year (U.S. Department of Justice, 2017). In order for behavior to be considered bullying, the behavior must be aggressive and include:

- An imbalance of power. Students who bully use their power–such as physical strength, access to embarrassing information, or popularity–to control or harm others. Power imbalances can change over time and in different situations, even if they involve the same people.

- Repetition of behavior. Bullying behaviors happen more than once and establish a pattern of behavior. One stand-alone hurtful comment or action is not the same as bullying.

There are generally three types of bullying: verbal bullying, social bullying, and physical bullying. Verbal bullying is saying mean things and includes behaviors such as teasing, name calling, inappropriate sexual comments, taunting and threatening to cause harm. Social bullying, sometimes referred to as relational bullying, involves hurting someone’s reputation or relationships. Social bullying includes leaving someone out on purpose, telling other children not to be friends with someone, spreading rumors about someone, and/or embarrassing someone in public. Physical bullying involves hurting a person’s body or possessions. Physical bullying includes behaviors such as kicking or hitting, spitting, tripping or pushing, taking or breaking someone’s things, and/or making rude or mean hand gestures. In 2017, about 42 percent of students who reported being bullied at school indicated that the bullying was related to at least one of the following characteristics: physical appearance (30%), race (10%), gender (8%), disability (7%), ethnicity (7%), religion (5%), and sexual orientation (4%) (U.S. Department of Justice, 2017).

Cyberbullying, also referred to as electronic bullying, is bullying that takes place using electronic technology. Electronic technology includes devices and equipment such as cell phones, computers and tablets, as well as communication tools such as social media sites, text messages, chat, and websites. Examples of cyberbullying include mean text messages or emails, rumors sent by email or posted on social networking sites, and embarrassing pictures, videos, websites, or fake profiles.

Unlike bullying, cyberbullying can happen 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and reach a student even when they are alone. It can happen any time of day or night. Cyberbullying messages can be posted anonymously and distributed quickly to a wide audience. It can be difficult and sometimes impossible to trace the source. Deleting inappropriate or harassing messages, texts, and pictures can be extremely difficult after they have been posted or sent.

Bullying and cyberbullying have significant implications when it comes to trauma and our students’ school and life experiences. Children who are cyberbullied or bullied in school are more likely to use drugs and alcohol, skip school, be unwilling to attend school, receive poor grades, have lower self-esteem and more health problems. There can also be the most devastating of consequences: a child committing suicide.

As an educator, you are in a position to prevent bullying or intervene when it happens. Later in this chapter, we will discuss how to create a positive classroom environment for students in order to mitigate the chances of bullying in school and beyond.

Critical Community Stakeholders in Classroom Environments

As teachers, we are not expected to create positive classroom environments all by ourselves. Community stakeholders, including school social workers and families, also play a critical role.

School Social Workers

With their unique training, perspective, and expertise, school social workers can be valuable assets in school communities. Introduced to the education system in 1906 as “visiting teachers,” school social workers were tasked with gathering the histories of students to assist in the evaluation process, and then delivering interventions based on the results.

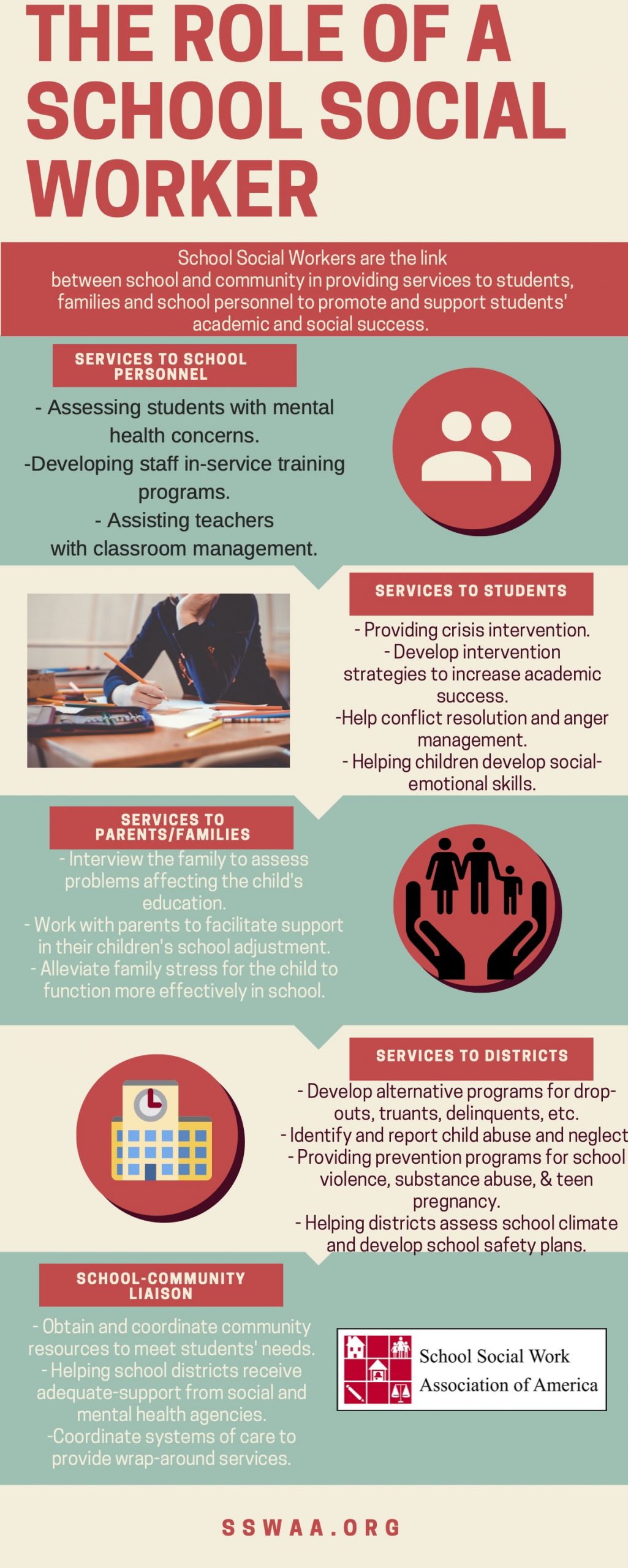

Today, school social workers are considered to be “trained mental health professionals who can assist with mental health concerns, behavioral concerns, positive behavioral support, academic, and classroom support, consultation with teachers, parents, and administrators as well as provide individual and group counseling/therapy” (School Social Work Association of America, n.d.). Although school social workers may not be utilized in all states or school districts, the benefits for those that do are clear. As members of school teams, they are able to assist at the building level as well as classroom, group, and individual levels to meet the social-emotional needs of both students and staff. Their commitment to bridging the gap between home and school can facilitate stronger engagement and relationships with caregivers in the academic lives of their children. Additionally, school social workers are educated in understanding the impact of systemic experiences and structures on the development of children and families. This knowledge is important in today’s schools as we learn more about the effects of adverse experiences on our students’ abilities to fully benefit from their education.

School social workers can provide prevention and intervention services at the building level, including developing and implementing social-emotional curricula aimed at improving emotional intelligence and developing a sense of belonging within the school setting. Support can be provided at the classroom level as well to provide more targeted interventions based on the need of small groups. Teachers can work with school social workers to discuss specific student and family concerns, gain ideas for social-emotional interventions, and to monitor the progress of students’ behavior. School social workers can also assist with prevention programs, such as those for reducing student drop-out or suicides, as well as targeting specific populations, such as students experiencing homelessness, who may need additional support.

At the family level, school social workers can connect families with community resources to increase stability, safety, and health within the community. School social workers can meet with families in their homes to better understand any specific concerns or needs the family may have and determine the appropriate interventions. Robert Constable (2016) stated, “The basic focus of the school social worker is the constellation of teacher, parent, and child. The social worker must be able to relate to and work with all aspects of the child’s situation, but the basic skill underlying all of this is assessment, a systematic way of understanding and communicating what is happening and what is possible” (p. 6). Operating from a strengths-based perspective, school social workers can engage with families in a nonjudgmental manner and ensure that all parties have a common understanding and goal.

Finally, the role of school social workers is heavily focused on ensuring the social-emotional health and needs of students are supported. Direct services provided can include individual and group counseling, as well as crisis response, such as conducting risk assessments for students experiencing suicidal ideation. Social workers can provide clinical intervention in a variety of school-related mental health concerns including anxiety, depression, coping skills, and emotional regulation. Services can also be provided to address social skills deficits including assisting students in understanding their social environment. The School Social Work Association of America (n.d.) provides a visual representation of The Role of School Social Workers.

Families and The Community

Sometime during your career, you may hear teachers talking about their students’ families in a way that conveys a deficit view of families by positioning families as “uncaring,” while the reality is likely quite different. Families might be unable to attend a conference due to various challenges with scheduling, transportation, childcare, or their own negative experiences in school. This statement also reveals misunderstandings of the differences between family involvement versus family engagement, two terms that are often used interchangeably but actually are distinct concepts.

Family Involvement vs. Family Engagement

Family involvement tends to be more school-oriented, whereas family engagement tends to be more family-oriented. Ferlazzo (2011) described family involvement as the school holding the expectations for family participation and telling families what they need to do. In other words, the school does things “to” or “for” families and families respond. For example, consider when it is time for teacher conferences: the school sends out a schedule, and the expectation is that families will come to school at the appointed time. The goal for these meetings is often a one-sided transition of information, where the teacher reports back to the family how the student is performing in class, while expecting the family to be somewhat passive acceptors of this information.

Family engagement, on the other hand, indicates working “with” families: sharing responsibility and working together to support children’s learning. In this case, when it is time for teacher conferences, the teachers are encouraged to work with families and find ways to communicate with all of them. While some families will come to school at the scheduled time, some might schedule a phone call when they are on break from work, while others might prefer to do FaceTime because they want to see the teacher. Teachers will also engage family members as contributors, asking them what they have seen at home, or what their celebrations, goals, or concerns are for their child’s learning.

Schools cannot exist without families, and therefore there is a great need for partnerships between schools and families. Families can contribute to school communities in a variety of ways, even well beyond volunteering in classrooms or contributing to required fundraisers. Families can use their firsthand knowledge of the local community to help connect teachers with community agencies or experts for a field trip or classroom visits. All students bring a wealth of background experiences–often built with their families–to the classroom each day, which can help students connect to and understand learning goals and the world around them. Remember that while there are some more visible, traditional forms of support (like volunteering or joining the PTA), families partner with educators in limitless ways to support a common goal: their child’s learning and growth.

Critical Lens: Cultural Norms for Family Engagement

Different cultures have different norms for how families should be involved in their child’s education. Some cultures believe that educators are the trained experts and leave their child’s learning fully up to the school as a sign of respect for the teacher’s position. Some cultures believe that families and teachers are co-educators. Be careful not to judge family engagement based on your own cultural background!

Building strong partnerships between schools and families also requires a reconfiguration of the traditional view of “family.” Be careful not to assume that a student’s family consists of a mother and father. Families might consist of same-sex parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, step-parents, adopted parents, foster parents, older siblings, and more. For this reason, using the word “family” instead of “parents” can be more inclusive. In addition, we need to view communities as part of families, and schools can engage with their community “families” in creative ways. For example, some schools have “grandmas.” These community grandmas come into the classroom a few days a week to tell stories about their lives and listen to students share their own stories. This partnership demonstrates a beautiful way to build meaningful relationships between the school and community.

Interrupting Bias and Stereotypes in School/Family Partnerships

Viewing children and families through one lens, a deficit lens, is harmful and imposes limits on what they can accomplish. Implicit biases and stereotypes are damaging to school-family partnerships and are often detrimental to students’ success. Let’s look at two fairly common stereotypes.

One common stereotype is that families do not come to school because they do not care. In reality, there are many possible reasons why families do not come to school. Edwards (2016) offers that families of color may have had unpleasant experiences in schools themselves and are not willing to succumb to the “ghosts” of school again. As children they were not welcome or well-treated in school and cannot bring themselves to enter the buildings again; schools were traumatic places.

Another common stereotype is that families have nothing to offer their children or school. In reality, families are their children’s first teachers. Deficit views of families negate the fact that prior to coming to school, children have learned their family’s language and culture by being immersed in them. Children learn their families’ and communities’ ways of knowing and being by interacting and engaging with community members and families.

To build stronger school-family partnerships, schools can reframe the traditional reliance upon family involvement instead of family engagement. The norm for involving families is that the school dictates the needs and reaches out to families, telling them the needs. Instead, reframing this partnership to one of family engagement invites collaboration and shifts from a deficit orientation to a strengths-based perspective. Families have a lot to offer in an educator’s work toward building positive classroom environments, and schools need to take note of the resources available in their community and extend invitations for meaningful work.

Strategies for Building a Positive Classroom Environment

The development of a strong sense of community and belonging in the classroom is essential to building relationships that may serve as protective factors for our students. Implementation of practices and approaches built around empathy, the ability to recognize and feel the emotions of others, has the ability to positively impact all students, but is critical to the success of students who have experienced adversity.

At times, it is difficult to separate our empathy with students from our sympathy for students. Some of our students experience such difficult lives and our sympathy leads us to expect less of them. Interacting with students from a place of sympathy does not build our connections with them and does not let them know we believe in them. Table 7.1 shows differences in statements focused on empathy versus sympathy.

Table 7.1: Statements Focused on Empathy vs. Sympathy

Empathy |

Sympathy |

| I can see you are frustrated right now. How can I help you? | I’m sorry you’re frustrated, but you need to get back to work. |

| Wow, you had a really hard morning. When I have a hard morning, sometimes I need a few minutes before I’m ready to work. Would you like some time before you get started? | Wow, what a horrible morning. You don’t have to do this assignment. |

| I noticed you aren’t with your friends like usual. Is there anything you want to talk about? | Why weren’t you with your friends today? |

| Can you tell me how you are feeling right now? | What’s wrong? |

It is our job as educators to create an environment that models empathy for students to facilitate trust and security. Bob Sornson (2014) states, “By helping children learn empathy, we raise the odds they will have strong positive social relationships, truly care for others, and be able to set appropriate limits in their own lives without using angry behaviors or words” (para. 2). Traditional elements of a classroom environment, including structured, predictable routines and morning meetings, can be expanded with the intention to increase opportunities for empathy on a daily basis. However, some traditional models of classroom management include practices that interfere with the development of healthy connections between teachers and our students. Building connections with students can be challenging at times and take effort and repeated attempts with students who have experienced adversity; furthermore, these relationships can be damaged quickly if we use practices that do not align with building empathy.

Table 7.2 provides an overview of some management practices to avoid and to use, though you will get much more in-depth information on classroom management strategies as you continue in your pathway as a preservice teacher.

Table 7.2: Classroom Management Practices

| Classroom Management Practices to Avoid | Classroom Management Practices to Use |

|

|

As you develop getting-to-know-you surveys or beginning-of-the-year activities, it is important to make sure all students will be able to answer the questions. Avoid questions that may be impacted by privilege such as those related to vacations or material items.

Mindfulness in the Educational Setting

The ability to self-regulate is an important developmental milestone for all students and requires co-regulation from a loving, consistent adult to develop in early childhood. The use of mindfulness-based activities in schools is a research-based strategy with benefits for students, teachers, and the classroom community as a whole. Strategies can include external and internal focuses as well as utilize the five senses to help students remain rooted in the present moment. Activities can be embedded into the structure of the daily classroom routine and increase the sense of calm across the environment. Mindfulness strategies can be modified and adapted to meet the needs of a variety of students. Utilizing these skills regularly in the classroom is a social-emotional strategy that can benefit all students regardless of their early life experiences.

Jon Kabat-Zinn (2003), an expert in mindfulness, defines it as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (p. 145). Simply put, it is intentionally noticing our internal and external environments without judging what we find. This intentional awareness requires consistent training and practice in order to benefit. Mindfulness can include a variety of activities based around movement, touch, breathing, and the senses as well as the use of reflection.

Students may need teaching practices to be adapted by using shorter activities, using more activities with movement (such as yoga), and using props or visual aides to assist them in focusing on specific sensations. Small things such as the use of a stuffed animal can be beneficial to teaching deep breathing by allowing the student to put it on their stomach and instructing them to make it go up and down using their breath. A strategy to use mindfulness to focus on sensations is the use of a mint to facilitate students’ ability to engage. Teachers can guide this practice by inviting students to use their senses to explore the mint. Questions that can be asked include: What color is the mint? Is there a pattern? What does the mint smell like? What does the mint feel like on your tongue? What does it taste like? How does the texture or size of the mint change over time? What sound does the mint make when you bite it? Having students focus on an object and use their senses to explore it, keeps students grounded in the present moment which is the essence of mindfulness practice. It is important to remember students may need concrete activities to be able to access the practices effectively. Additionally, students should be given the option to keep their eyes open during any mindfulness activity to promote safety and trust.

Mindfulness strategies can be simple activities which can be easily implemented in the daily routines of a classroom. It is important to consider the developmental age of our students as well as what activities might be appropriate on a given day. Implementation of practices should begin with short activities and increase as students are able to successfully engage in the strategies. Some activities may require props to implement and others can be done using visual or auditory guides from the internet. Waterford.org provides a list of 51 Mindful Exercises for Kids in the Classroom that can be accessed and used with a variety of age groups. Activities for secondary students are available from PositivePsychology.com under 25 Mindfulness Activities for Children and Teens. Remember, implementing mindfulness strategies in the classroom can cost nothing, other than the commitment to practicing intentionally and protecting time within the day for our classroom community.

Benefits of Mindfulness

The regular and consistent use of mindfulness strategies has been found to be beneficial for the whole person, including both physical and mental well-being. Hofmann et al. (2010) reviewed 39 studies on the impact of mindfulness-based therapy on a variety of mental health and physical diagnoses. Results of the meta-analysis revealed improvement in symptoms of anxiety and depression, including those that may be related to an underlying medical condition. Additionally, the benefits of mindfulness were not found to be relative to specific diagnoses because of the impact on general wellbeing. Within the school system, mindfulness has also been proven to positively impact a variety of areas for students, including attention, emotional regulation, compassion, and reduction of stress and anxiety (Mindful Schools, n.d.). The consistent use of these strategies also benefits teachers and improves teacher-student relationships (Flook et al., 2013).

The benefits of stronger emotional regulation through mindfulness-based practices extend into all areas of our students’ lives. Schonert-Reichl et al. (2015) found implementation of a social-emotional curriculum for as little as four months led to improved behavioral and academic functioning for students. Additional benefits include improved impulse control, focus and attention, and stronger peer relationships through the development of compassion and empathy for others. The implementation of a regular mindfulness practice in the classroom benefits not only individual students, but also the entire classroom community, including the teachers.

Conclusion

Before students can learn, they must first feel safe, supported, and valued. Creating empathy-driven classroom environments involves intentional decisions about specific elements under the educator’s control, such as an accessible physical arrangement of the classroom, an affirming atmosphere, and using humanizing management strategies while intentionally avoiding those that cause humiliation or shame. Additionally, educators can partner with critical community stakeholders, such as school social workers and family or community members, to access additional resources to support students’ success.

Creating empathy-driven classroom environments also involves awareness of elements that are not under the educator’s control. Adverse childhood experiences are common within our classrooms, with varying degrees of impact on the social, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive functioning of our students. Understanding the unique histories of each of our students is important, but so is uncovering who they are as individuals including what makes them resilient. A history of adverse experiences does not mean our students cannot learn and grow and develop healthy relationships. It means they have experiences that may change the path that gets them there and will need the positive adult connection we can provide as their teacher even more.

To create an empathy-focused classroom environment, there are certain elements to include–such as routines, morning meetings, and developing individual relationships with students–and elements to avoid, such as clip charts or card-flipping systems, group punishment, and public humiliation. Building and implementing a trauma-informed classroom with empathy at the core is a practice that supports all students and will increase a sense of community and belonging for all.

Building and modeling empathy fosters a reciprocal relationship in which students can feel educators’ genuine care and concern for their best interests. We lay the foundation for our students’ success by intentionally creating a humanizing classroom environment in which they can learn and grow.

- http://www.justicepolicy.org/news/8775 ↵

Elements of a classroom community that include physical set-up, overall atmosphere, behavior management, and other considerations.

From the work of Anda & Felitti (1998), sets of childhood experiences that may include abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction that lead to increased social, emotional, behavioral, and academic challenges.

The ability to bounce back from adverse experiences.

A caregiver’s action, or failure to act, resulting in death, significant physical or emotional harm, or the exploitation of a child under the age of 18.

Failure to consistently meet basic needs such as food and shelter, as well as providing a safe, clean environment.

Succession of 8 hierarchical needs, divided into deficiency needs (physiological, safety, belongingness & love, and esteem needs) and growth needs (need for knowledge & understanding, aesthetic needs, self actualization, and transcendence).

The failure to meet or recognize a child’s emotional needs.

Aggressive behavior that involves an imbalance of power and repetition of behavior. Can be verbal, social, or physical.

Bullying that takes place using electronic technology.

Trained mental health professionals who can assist with mental health concerns, behavioral concerns, positive behavioral support, academic, and classroom support, consultation with teachers, parents, and administrators as well as provide individual and group counseling/therapy.

School-oriented approach toward involving families in schools, with the school holding the expectations for family participation and telling families what they need to do.

Family-oriented approach toward building home-school partnerships that share responsibility for and work together to support children’s learning.

The ability to recognize and feel the emotions of others.