10 Curriculum, Assessment, and Instruction

A substitute teacher was supposed to give an assessment while the classroom teacher was away, but one student refused to take the test. “He started yelling and walked out of the room, saying he wasn’t going to take this test that the teacher left for him. He kept saying that he is supposed to have questions read aloud to him, but that isn’t fair and I wasn’t going to do it!” Sometimes we think that fairness means everyone is treated the same way, but in reality, “fairness” involves meeting the needs of different students. In this example, the student had an IEP accommodation that allowed him to have tests read aloud to him. When considering instruction, and assessment, sometimes treating all students the same is actually quite unfair, since students have different learning needs and strengths.

In this chapter, we will begin to explore the inner workings of classroom curriculum. Assessment, and instruction all intertwine within a classroom curriculum, and being aware of the relationships among the various components of curriculum can lead to appropriate and fair assessments and instruction.

Chapter Outline

Types of Curriculum

You have had some kind of experience with schooling, whether it was homeschool, private school, public school, or some combination of those. No matter the setting where you learned, someone decided what you would learn. This is the curriculum. It reaches far beyond the textbooks that you might have used or the novels that you read. It even includes things that are unstated.

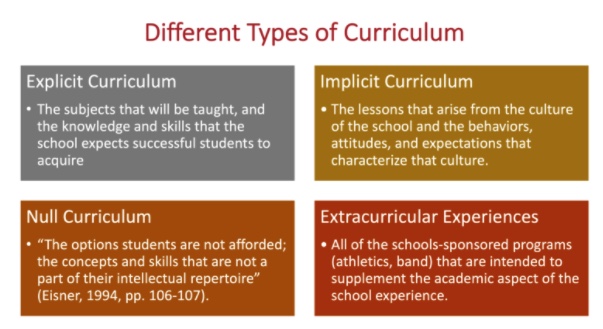

There are different kinds of curriculum, including the explicit curriculum, implicit curriculum, and null curriculum. Explicit curriculum is the state, district, and schools’ formal accounting of what they teach. Another term for explicit curriculum is formal curriculum. The explicit or formal curriculum is often laid out in standards or other curricular materials. Implicit curriculum,or informal curriculum, involves hidden messages that students learn from schooling that aren’t specifically in the standards and possibly aren’t even explicitly taught.  For example, students may see bulletin board displays where people who look like them are missing and therefore feel like they do not belong in that classroom, or they may see the way the teacher treats students when it comes to conflict and realize the teacher displays favoritism towards certain students. Finally, null curriculum is made up of those things that are not taught in schools at all for a variety of reasons, such as contributions in science by scholars of color or women (Eisner, as cited in Milner, 2017). Finally, extra-curricular curriculum includes school-sponsored opportunities that fall outside of academic requirements prescribed on the local and state levels. Examples of extra-curricular activities include participation in sports, music, student governance, yearbook, school newspaper, and academic clubs. Extracurricular participation is a strategy to promote school connectedness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Extracurricular activities are often associated with many positive outcomes such as higher academic achievement and decreased school dropout (Farb & Matjasko, 2012). According to the United States National Center for Education Statistics (2012), sports are the most common type of extracurricular activity among secondary school students, with 44% of high school seniors reporting participation in some type of sport. Additionally, 21% of students participate in music activities, as well as clubs, such as academic (21%), hobby (12%), and vocational clubs (16%).

For example, students may see bulletin board displays where people who look like them are missing and therefore feel like they do not belong in that classroom, or they may see the way the teacher treats students when it comes to conflict and realize the teacher displays favoritism towards certain students. Finally, null curriculum is made up of those things that are not taught in schools at all for a variety of reasons, such as contributions in science by scholars of color or women (Eisner, as cited in Milner, 2017). Finally, extra-curricular curriculum includes school-sponsored opportunities that fall outside of academic requirements prescribed on the local and state levels. Examples of extra-curricular activities include participation in sports, music, student governance, yearbook, school newspaper, and academic clubs. Extracurricular participation is a strategy to promote school connectedness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Extracurricular activities are often associated with many positive outcomes such as higher academic achievement and decreased school dropout (Farb & Matjasko, 2012). According to the United States National Center for Education Statistics (2012), sports are the most common type of extracurricular activity among secondary school students, with 44% of high school seniors reporting participation in some type of sport. Additionally, 21% of students participate in music activities, as well as clubs, such as academic (21%), hobby (12%), and vocational clubs (16%).

There is immense power in determining what students will learn, with many competing forces at play. Because schooling in the United States is left to the jurisdiction of individual states, certain content is viewed, valued, and taught differently depending on the collective values of the state or county. For example, some students are taught about the Civil War as the “War of Northern Aggression,” while other schools may not allow confederate flags in their buildings or on school grounds. Historical events are a part of the curriculum, but in many cases these have been boiled down to the simplest pieces of information. Consider, for example, the difference between the following two lesson objectives: “Identify that Abe Lincoln wears a top hat” and “Explain how and why Abe Lincoln created the Emancipation Proclamation.” Imagine how different learning could be if more complex and important details were a part of the curriculum for all students.

Critical Lens: Racial Justice in the Curriculum

Recent concerns and protests about racial justice in the United States are another example of the tensions among explicit, implicit, and null curricula. Some schools may openly address and discuss protests for racial justice, while other schools may not mention them at all. The reasons for not addressing this topic range from not wanting to upset students or parents to openly racist thinking at the classroom, district, or state level. However, if something is never mentioned in school and therefore becomes part of the null curriculum, students take note of what is missing. Milner (2017) describes events like the violence in Charlottesville in 2017 as exactly the kind of topic that students must learn about in schools to cement the importance of social justice for future generations.

Assessment

Even though you may think of instruction–the day-to-day activities of teaching–as the biggest part of your job as a future educator, assessment should actually come first. If you are following the backward design process, you should think first about your objectives and assessments, and then about the activities that the students will do.

It is likely that when you think of assessment, you think of the grade you received at the end of an instructional unit. However, there are many kinds of assessment that serve different purposes. Table 6.1 outlines the differences among three key types of assessments: diagnostic, formative, and summative.

Table 6.1: Types of Assessments

Type |

Timing/Scoring |

Purpose |

Formats |

| Diagnostic |

|

|

|

| Formative |

|

|

|

| Summative |

|

|

|

Assessment can also be formal or informal. Formal assessments measure systematically what students have learned, often at the end of a course or school year. Standardized tests are a common example of formal assessments. These high-stakes, formal assessments are designed to measure how well students have mastered the content listed in the standards. On the other hand, informal assessments tend to be local, non-standardized, and contextualized in daily classroom learning activities. Informal assessments are usually performance-based, meaning students are performing, or demonstrating, their understanding through a specific task. Teachers design assessments and may evaluate them with grades, rubrics, checklists, or other scoring conventions.

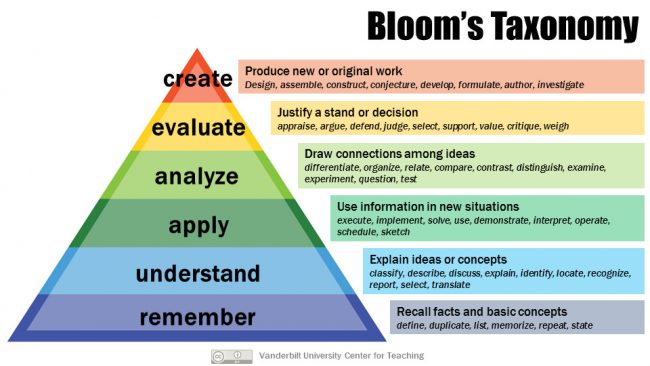

You will learn more about how to design high-quality assessments as you continue your journey toward becoming a teacher. For now, remember that high-quality assessments should always relate to the standards you taught in that particular lesson. This is called alignment. In addition, good assessments ask the right questions. For example, consider which of the following is more important as a life-long literacy skill: matching a secondary character in a text to a short phrase about what that person did, or presenting a coherent argument that advances your position on a controversial topic? A useful tool for thinking about levels of questioning is Bloom’s Taxonomy (Figure 6.3). Bloom’s Taxonomy is a framework (Bloom et al., 1956) that divides levels of thinking into six categories, ranging from Knowledge to Evaluation. In response to some criticism, the taxonomy was later revised by a group of scholars, including Krathwohl (2002). The new version of the taxonomy included levels ranging from Remember to Create. It is important to understand that the framework is not meant to serve as a ladder that students must climb, where simpler knowledge and questions must always come first; rather, it is possible for students at all levels to consider information at all levels and move among them. This framework enables teachers to think about the kinds of questions they ask, and vary them as needed. Less experienced teachers tend to rely more upon lower-level questions that require basic recall skills, so be intentional about asking questions that challenge students to venture into other levels of the taxonomy as well.

Figure 6.3: Bloom’s Taxonomy (Revised)

Designing and administering assessments that align with your standards and engage students at various levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy is an important first step, but another key part of effective assessments is analyzing the data you collect. Analysis of data can occur on individual student, small group, or whole class levels. If many students demonstrate a similar misunderstanding on an assessment, that data indicates the teacher should re-teach that content to increase students’ mastery. Data-driven instruction looks at the results of various assessments when considering next instructional steps. This analysis can be done by individual teachers or with colleagues in a PLC.

Assessment and grades are not the same. Grades can be a form of assessment, but not all assessments are graded. Assessments can include both quantitative and qualitative data. For example, observing students during an activity would not be a grade, but it would give you important information about what a student does or does not understand. There are many practices that exist to support students during assessments, such as IEP accommodations, differentiated assessments, retakes, and no-zero policies. Grading involves assigning scores or labels–such as letter grades, rubric scores, complete or incomplete labels, or numeric values–to a student’s performance on a task.

The issue of grading is complex and often confusing for new teachers. There may be department-, school-, or district-wide rules about how many grades a teacher should have in a quarter or semester. Some parents and students are very focused on high grades, even if they don’t reflect the student’s actual level of understanding. There could also be policies about homework: is it graded or ungraded? Do students receive zeros for work that is not turned in, or is the lowest grade possible a 60? Most would argue that the primary purpose of the grading system is to clearly, accurately, consistently, and fairly communicate learning progress and achievement to students, families, postsecondary institutions, and prospective employers (Great Schools Partnerships, 2021); however, grading can sometimes interfere with assessments of students’ actual understanding.

Critical Lens: Reducing Bias in Grading

In an ideal world, grades and assessments are fair and impartial. However, the reality is that bias often creeps into assessment systems. One simple work-around is to use rubrics with specific criteria. Quinn (2021) conducted an experiment in which he gave teachers two second grade writing samples, one presented as a Black student’s work and one as a White student’s. Teachers gave the White student higher scores except when they used a grading rubric with specific criteria, which caused the pre-existing racial bias in the scores to disappear. Therefore, rubrics not only help students know up front what expectations are for an assignment, but also reduce opportunities for bias to impact grading.

Instruction

Now that we’ve laid the foundation for an effective lesson by discussion planning and assessment, we can turn to instruction. Instruction involves the actual act of teaching a lesson and is usually what comes to mind when you envision teaching. You likely have experienced both good and poor teaching in your life as a student. Teaching is not telling. To teach well requires careful planning and knowledge of the learners in the room. There are various tools, techniques, and strategies that help teachers organize their instruction more logically and deliver it appropriately.

Teaching strategies are usually a series of steps that a teacher might have the students follow to encourage interaction or deeper thinking during instruction; strategies usually take from 5 to 15 minutes to enact during a lesson. An example of a strategy is “think-pair-share,” where a student turns to a partner to discuss a question or prompt before sharing with a larger group. Other strategies include using graphic organizers or creating metaphors to help students see content in a new way. You will have entire classes about teaching strategies in different content areas, often called methods courses, as you continue in your journey toward becoming a teacher. For now, we’ll investigate one very powerful, research-based strategy that can be used in all grades and content areas: Think-Pair-Share.

Think-Pair-Share is a particularly effective strategy because it allows students to share ideas with just one other person before being asked to share with the class. Students can have an opportunity to articulate their ideas prior to whole-class discussion. Extended Think-Pair-Share is a strategy used for English Learners. Instead of just an open-ended dialogue, students are prompted to use sentence frames, such as “I think the experiment showed us__________________ because I saw ___________happen.” Or, “That character in the story is very ______________. I know this because he _____________”. In this way, the dialogue is more structured with English Learners practicing correct English syntax in the process. This video shows a math teacher using the Think-Pair-Share strategy during a lesson.

When planning instructional activities, always keep them aligned with your standards, objectives, and assessments. While it can be tempting to turn to Teachers Pay Teachers, Pinterest, or TikTok for instructional inspiration, many of these “fun” activities do not result in meaningful learning. Always keep your instructional goals at the forefront of your selection of instructional activities.

Conclusion

Curriculum, planning, assessment, and instruction are all inextricably linked. Planning instruction is like a spider web, where all of the threads are connected in a carefully designed pattern. There are different kinds of spider webs, just as there are different ways to plan and deliver instruction and assessment. In the next chapter, we will take a closer look at planning curriculum.

Curriculum, planning, assessment, and instruction are all inextricably linked. Planning instruction is like a spider web, where all of the threads are connected in a carefully designed pattern. There are different kinds of spider webs, just as there are different ways to plan and deliver instruction and assessment. In the next chapter, we will take a closer look at planning curriculum.

The state, district, and schools’ formal accounting of what they teach. Also called formal curriculum.

The state, district, and schools’ formal accounting of what they teach. Also called explicit curriculum.

Hidden messages that students learn from schooling that aren’t specifically in the standards and possibly aren’t even explicitly taught. Also called informal curriculum.

Hidden messages that students learn from schooling that aren’t specifically in the standards and possibly aren’t even explicitly taught. Also called implicit curriculum.

Topics that are not taught in schools at all for a variety of reasons.

Type of assessment administered before instruction to learn what students know prior to instruction.

Type of assessment given during instruction that gives teachers insight into students' understanding as it is forming.

Type of graded assessment given after instruction to show what students have learned.

Measure systematically what students have learned, often at the end of a course or school year, such as with a standardized test.

Assessments that are local, non-standardized, and contextualized in daily classroom learning activities; often performance-based.

Characteristic of well-planned instruction in which multiple elements align with each other (i.e., standards, assessment, and instruction).

Framework designed by Benjamin Bloom and colleagues in 1956, and later revised in 2001. Divides educational goals/cognitive processes into six categories of increasing complexity: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and create.

Looking at the results of various assessments when considering next instructional steps.

A series of steps that a teacher might have the students follow to encourage interaction or deeper thinking during instruction; usually take 5-15 minutes to enact during a lesson.