Chapter 7: Leading People Within Organizations

Leading People Within Organizations

Leadership may be defined as the act of influencing others to work toward a goal. Leaders exist at all levels of an organization. Some leaders hold a position of authority and may utilize the power that comes from their position, as well as their personal power to influence others. They are called formal leaders. In contrast, informal leaders are without a formal position of authority within the organization but demonstrate leadership by influencing others through personal forms of power. One caveat is important here: Leaders do not rely on the use of force to influence people. Instead, people willingly adopt the leader’s goal as their own goal. If a person is relying on force and punishment, the person is a dictator, not a leader.

What makes leaders effective? What distinguishes people who are perceived as leaders from those who are not perceived as leaders? More importantly, how do we train future leaders and improve our own leadership ability? These are important questions that have attracted scholarly attention in the past several decades. In this chapter, we will review the history of leadership studies and summarize the major findings relating to these important questions. Around the world, we view leaders as at least partly responsible for their team or company’s success and failure. Company CEOs are paid millions of dollars in salaries and stock options with the assumption that they hold their company’s future in their hands. In politics, education, sports, profit and nonprofit sectors, the influence of leaders over the behaviors of individuals and organizations is rarely questioned. When people and organizations fail, managers and CEOs are often viewed as responsible. Some people criticize the assumption that leadership always matters and call this belief “the romance of leadership.” However, research evidence pointing to the importance of leaders for organizational success is accumulating (Hogan, Curphy, & Hogan, 1994).

11.1 Taking on the Pepsi Challenge: The Case of Indra Nooyi

She is among the top 100 most influential people according to Time magazine’s 2008 list. She is also number 5 in Forbes’s “Most Influential Women in the World” (2007), number 1 in Fortune’s “50 Most Powerful Women” (2006), and number 22 in Fortune’s “25 Most Powerful People in Business” (2007). The lists go on and on. To those familiar with her work and style, this should come as no surprise: Even before she became the CEO of PepsiCo Inc. (NYSE: PEP) in 2006, she was one of the most powerful executives at PepsiCo and one of the two candidates being groomed for the coveted CEO position. Born in Chennai, India, Nooyi graduated from Yale’s School of Management and worked in companies such as the Boston Consulting Group Inc., Motorola Inc., and ABB Inc. She also led an all-girls rock band in high school, but that is a different story.

What makes her one of the top leaders in the business world today? To start with, she has a clear vision for PepsiCo, which seems to be the right vision for the company at this point in time. Her vision is framed under the term “performance with purpose,” which is based on two key ideas: tackling the obesity epidemic by improving the nutritional status of PepsiCo products and making PepsiCo an environmentally sustainable company. She is an inspirational speaker and rallies people around her vision for the company. She has the track record to show that she means what she says. She was instrumental in PepsiCo’s acquisition of the food conglomerate Quaker Oats Company and the juice maker Tropicana Products Inc., both of which have healthy product lines. She is bent on reducing PepsiCo’s reliance on high-sugar, high-calorie beverages, and she made sure that PepsiCo removed trans fats from all its products before its competitors. On the environ- mental side, she is striving for a net zero impact on the environment. Among her priorities are plans to reduce the plastic used in beverage bottles and find biodegradable packaging solutions for PepsiCo products. Her vision is long term and could be risky for short-term earnings, but it is also timely and important.

Those who work with her feel challenged by her high-performance standards and expectation of excellence. She is not afraid to give people negative feedback—and with humor, too. She pushes people until they come up with a solution to a problem and does not take “I don’t know” for an answer. For example, she insisted that her team find an alternative to the expensive palm oil and did not stop urging them forward until the alternative arrived: rice bran oil.

Nooyi is well liked and respected because she listens to those around her, even when they disagree with her. Her background cuts across national boundaries, which gives her a true appreciation for diversity, and she expects those around her to bring their values to work. In fact, when she graduated from college, she wore a sari to a job interview at Boston Consulting, where she got the job. She is an unusually collaborative person in the top suite of a Fortune 500 company, and she seeks help and information when she needs it. She has friendships with three ex-CEOs of PepsiCo who serve as her informal advisors, and when she was selected to the top position at PepsiCo, she made sure that her rival for the position got a pay raise and was given influence in the company so she did not lose him. She says that the best advice she received was from her father, who taught her to assume that people have good intentions. Nooyi notes that expecting people to have good intentions helps her prevent misunderstandings and show empathy for them. It seems that she is a role model to other business leaders around the world, and PepsiCo is well positioned to tackle the challenges the future may bring.

Based on information from Birger, J., Chandler, C., Frott, J., Gimbel, B., Gumbel, P., et al. (2008, May 12). The best advice I ever got. Fortune, 157(10), 70–80; Brady, D. (2007, June 11). Keeping cool in hot water. BusinessWeek. Retrieved April 30, 2010, from http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/07_24/ b4038067.htm; Compton, J. (2007, October 15). Performance with purpose. Beverage World, 126(10), 32; McKay, B. (2008, May 6). Pepsi to cut plastic used in bottles. Wall Street Journal, Eastern edition, p. B2; Morris, B., & Neering, P. A. (2008, May 3). The Pepsi challenge: Can this snack and soda giant go healthy? CEO Indra Nooyi says yes but cola wars and corn prices will test her leadership. Fortune, 157(4), 54–66; Schultz, H. (2008, May 12). Indra Nooyi. Time, 171(19), 116–117; Seldman, M. (2008, June). Elevating aspi- rations at PepsiCo. T+D, 62(6), 36–38; The Pepsi challenge (2006, August 19). Economist. Retrieved April 30, 2010, from http://www.economist.com/business-finance/displaystory.cfm?story_id =7803615.

11.2 Who Is a Leader? Trait Approaches to Leadership

- Learn the position of trait approaches in the history of leadership studies.

- Explain the traits that are associated with leadership.

- Discuss the limitations of trait approaches to leadership.

The earliest approach to the study of leadership sought to identify a set of traits that distinguished leaders from nonleaders. What were the personality characteristics and the physical and psychological attributes of people who are viewed as leaders? Because of the problems in measurement of personality traits at the time, different studies used different measures. By 1940, researchers concluded that the search for leadership-defining traits was futile. In recent years, though, after the advances in personality literature such as the development of the Big Five personality framework, researchers have had more success in identifying traits that predict leadership (House & Aditya, 1997). Most importantly, charismatic leader- ship, which is among the contemporary approaches to leadership, may be viewed as an example of a trait approach.

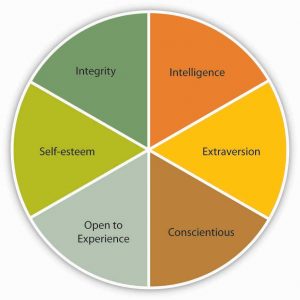

The traits that show relatively strong relations with leadership are discussed below (Judge et al., 2002).

Intelligence

General mental ability, which psychologists refer to as “g” and which is often called “IQ” in everyday language, has been related to a person’s emerging as a leader within a group. Specifically, people who have high mental abilities are more likely to be viewed as leaders in their environment (House & Aditya, 1997; Ilies, Gerhardt, & Huy, 2004; Lord, De Vader, & Alliger, 1986; Taggar, Hackett, & Saha, 1999). We should caution, though, that intelligence is a positive but modest predictor of leadership, and when actual intelligence is measured with paper-and-pencil tests, its relationship to leadership is a bit weaker compared to when intelligence is defined as the perceived intelligence of a leader (Judge, Colbert, & Ilies, 2004). In addition to having a high IQ, effective leaders tend to have high emotional intelligence (EQ). People with high EQ demonstrate a high level of self awareness, motivation, empathy, and social skills. The psychologist who coined the term emotional intelligence, Daniel Goleman, believes that IQ is a threshold quality: It matters for entry- to high-level management jobs, but once you get there, it no longer helps leaders, because most leaders already have a high IQ. According to Goleman, what differentiates effective leaders from ineffective ones becomes their ability to control their own emotions and understand other people’s emotions, their internal motivation, and their social skills (Goleman, 2004).

Big 5 Personality Traits

Psychologists have proposed various systems for categorizing the characteristics that make up an individual’s unique personality; one of the most widely accepted is the “Big Five” model, which rates an individual according to Openness to experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Several of the Big Five personality traits have been related to leadership emergence (whether someone is viewed as a leader by others) and effectiveness (Judge et al., 2002).

Big Five Personality Traits

Trait |

Description |

| Openness | Being curious, original, intellectual, creative, and open to new ideas. |

| Conscientiousness | Being organized, systematic, punctual, achievement-oriented, and dependable. |

| Extraversion | Being outgoing, talkative, sociable, and enjoying social situations. |

| Agreeableness | Being affable, tolerant, sensitive, trusting, kind, and warm. |

| Neuroticism | Being anxious, irritable, temperamental, and moody. |

For example, extraversion is related to leadership. Extraverts are sociable, assertive, and energetic people. They enjoy interacting with others in their environment and demonstrate self-confidence. Because they are both dominant and sociable in their environment, they emerge as leaders in a wide variety of situations. Out of all personality traits, extraversion has the strongest relationship with both leader emergence and leader effectiveness. This is not to say that all effective leaders are extraverts, but you are more likely to find extraverts in leadership positions. An example of an introverted leader is Jim Buck- master, the CEO of Craigslist. He is known as an introvert, and he admits to not having meetings because he does not like them (Buckmaster, 2008). Research shows that another personality trait related to leadership is conscientiousness. Conscientious people are organized, take initiative, and demonstrate persistence in their endeavors. Conscientious people are more likely to emerge as leaders and be effective in that role. Finally, people who have openness to experience—those who demonstrate originality, creativity, and are open to trying new things—tend to emerge as leaders and also be quite effective.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is not one of the Big Five personality traits, but it is an important aspect of one’s personality. The degree to which a person is at peace with oneself and has an overall positive assessment of one’s self worth and capabilities seem to be relevant to whether someone is viewed as a leader. Leaders with high self-esteem support their subordinates more and, when punishment is administered, they punish more effectively (Atwater et al., 1998; Niebuhr, 1984).

It is possible that those with high self-esteem have greater levels of self-confidence and this affects their image in the eyes of their followers. Self-esteem may also explain the relationship between some physical attributes and leader emergence. For example, research shows a strong relationship between being tall and being viewed as a leader (as well as one’s career success over life). It is proposed that self-esteem may be the key mechanism linking height to being viewed as a leader, because people who are taller are also found to have higher self-esteem and therefore may project greater levels of charisma as well as confidence to their followers (Judge & Cable, 2004).

Integrity

Research also shows that people who are effective as leaders tend to have a moral compass and demonstrate honesty and integrity (Reave, 2005). Leaders whose integrity is questioned lose their trustworthiness, and they hurt their company’s business along the way. For example, when it was revealed that Whole Foods Market CEO John Mackey was using a pseudonym to make negative comments online about the company’s rival Wild Oats Markets Inc., his actions were heavily criticized, his leadership was questioned, and the company’s reputation was affected (Farrell & Davidson, 2007).

There are also some traits that are negatively related to leader emergence and being successful in that position. For example, agreeable people who are modest, good natured, and avoid conflict are less likely to be perceived as leaders (Judge et al., 2002).

Despite problems in trait approaches, these findings can still be useful to managers and companies. For example, knowing about leader traits helps organizations select the right people into positions of responsibility. The key to benefiting from the findings of trait researchers is to be aware that not all traits are equally effective in predicting leadership potential across all circumstances. Some organizational situations allow leader traits to make a greater difference (House & Aditya, 1997). For example, in small, entrepreneurial organizations where leaders have a lot of leeway to determine their own behavior, the type of traits leaders have may make a difference in leadership potential. In large, bureaucratic, and rule- bound organizations such as the government and the military, a leader’s traits may have less to do with how the person behaves and whether the person is a successful leader (Judge et al., 2002). Moreover, some traits become relevant in specific circumstances. For example, bravery is likely to be a key characteristic in military leaders, but not necessarily in business leaders. Scholars now conclude that instead of trying to identify a few traits that distinguish leaders from nonleaders, it is important to identify the conditions under which different traits affect a leader’s performance, as well as whether a person emerges as a leader (Hackman & Wageman, 2007).

Key Takeaway

Many studies searched for a limited set of personal attributes, or traits, which would make someone be viewed as a leader and be successful as a leader. Some traits that are consistently related to leadership include intelligence (both mental ability and emotional intelligence), personality (extraversion, conscientiousness, openness to experience, self-esteem), and integrity. The main limitation of the trait approach was that it ignored the situation in which leadership occurred. Therefore, it is more useful to specify the conditions under which different traits are needed.

11.3 What Do Leaders Do? Behavioral Approaches to Leadership

Leader Behaviors

When trait researchers became disillusioned in the 1940s, their attention turned to studying leader behaviors. What did effective leaders actually do? Which behaviors made them perceived as leaders? Which behaviors increased their success? To answer these questions, researchers at Ohio State University and the University of Michigan used many different techniques, such as observing leaders in laboratory set- tings as well as surveying them. This research stream led to the discovery of two broad categories of behaviors: task-oriented behaviors (sometimes called initiating structure) and people-oriented behaviors (also called consideration). Task-oriented leader behaviors involve structuring the roles of subordinates, providing them with instructions, and behaving in ways that will increase the performance of the group. Task-oriented behaviors are directives given to employees to get things done and to ensure that organizational goals are met. People-oriented leader behaviors include showing concern for employee feelings and treating employees with respect. People-oriented leaders genuinely care about the well- being of their employees, and they demonstrate their concern in their actions and decisions. At the time, researchers thought that these two categories of behaviors were the keys to the puzzle of leadership (House & Aditya, 1997). However, research did not support the argument that demonstrating both of these behaviors would necessarily make leaders effective (Nystrom, 1978).

When we look at the overall findings regarding these leader behaviors, it seems that both types of behaviors, in the aggregate, are beneficial to organizations, but for different purposes. For example, when leaders demonstrate people-oriented behaviors, employees tend to be more satisfied and react more positively. However, when leaders are task oriented, productivity tends to be a bit higher (Judge, Piccolo, & Ilies, 2004). Moreover, the situation in which these behaviors are demonstrated seems to matter. In small companies, task-oriented behaviors were found to be more effective than in large companies (Miles & Petty, 1977). There is also some evidence that very high levels of leader task-oriented behaviors may cause burnout with employees (Seltzer & Numerof, 1988).

Leader Decision Making

Another question behavioral researchers focused on involved how leaders actually make decisions and the influence of decision-making styles on leader effectiveness and employee reactions. Three types of decision-making styles were studied. In authoritarian decision making, leaders make the decision alone without necessarily involving employees in the decision-making process. When leaders use democratic decision making, employees participate in the making of the decision. Finally, leaders using laissez-faire decision making leave employees alone to make the decision. The leader provides minimum guidance and involvement in the decision.

As with other lines of research on leadership, research did not identify one decision-making style as the best. It seems that the effectiveness of the style the leader is using depends on the circumstances. A review of the literature shows that when leaders use more democratic or participative decision-making styles, employees tend to be more satisfied; however, the effects on decision quality or employee productivity are weaker. Moreover, instead of expecting to be involved in every single decision, employees seem to care more about the overall participativeness of the organizational climate (Miller & Monge, 1986). Different types of employees may also expect different levels of involvement. In a research organization, scientists viewed democratic leadership most favorably and authoritarian leadership least favorably (Baumgartel, 1957), but employees working in large groups where opportunities for member interaction was limited preferred authoritarian leader decision making (Vroom & Mann, 1960). Finally, the effectiveness of each style seems to depend on who is using it. There are examples of effective leaders using both authoritarian and democratic styles. At Hyundai Motor America, high-level managers use authoritarian decision-making styles, and the company is performing very well (Deutschman, 2004; Welch, Kiley, & Ihlwan, 2008).

The track record of the laissez-faire decision-making style is more problematic. Research shows that this style is negatively related to employee satisfaction with leaders and leader effectiveness (Judge & Piccolo, 2004). Laissez-faire leaders create high levels of ambiguity about job expectations on the part of employees, and employees also engage in higher levels of conflict when leaders are using the laissez- faire style (Skogstad et al., 2007).

Leadership Assumptions about Human Nature

Why do some managers believe that the only way to manage employees is to force and coerce them to work while others adopt a more humane approach? Douglas McGregor, an MIT Sloan School of Management professor, believed that a manager’s actions toward employees were dictated by having one of two basic sets of assumptions about employee attitudes. His two contrasting categories, outlined in his 1960 book, The Human Side of Enterprise, are known as Theory X and Theory Y.

According to McGregor, some managers subscribe to Theory X. The main assumptions of Theory X man- agers are that employees are lazy, do not enjoy working, and will avoid expending energy on work whenever possible. For a manager, this theory suggests employees need to be forced to work through any number of control mechanisms ranging from threats to actual punishments. Because of the assumptions they make about human nature, Theory X managers end up establishing rigid work environments. Theory X also assumes employees completely lack ambition. As a result, managers must take full responsibility for their subordinates’ actions, as these employees will never take initiative outside of regular job duties to accomplish tasks.

In contrast, Theory Y paints a much more positive view of employees’ attitudes and behaviors. Under Theory Y, employees are not lazy, can enjoy work, and will put effort into furthering organizational goals.

Because these managers can assume that employees will act in the best interests of the organization given the chance, Theory Y managers allow employees autonomy and help them become committed to particular goals. They tend to adopt a more supportive role, often focusing on maintaining a work environment in which employees can be innovative and prosperous within their roles.

One way of improving our leadership style would be to become conscious about our theories of human nature, and question the validity of our implicit theories.

Source: McGregor, D. (1960). Human side of enterprise. New York: McGraw Hill.

Limitations of Behavioral Approaches

Behavioral approaches, similar to trait approaches, fell out of favor because they neglected the environment in which behaviors are demonstrated. The hope of the researchers was that the identified behaviors would predict leadership under all circumstances, but it may be unrealistic to expect that a given set of behaviors would work under all circumstances. What makes a high school principal effective on the job may be very different from what makes a military leader effective, which would be different from behaviors creating success in small or large business enterprises. It turns out that specifying the conditions under which these behaviors are more effective may be a better approach.

Key Takeaway

When researchers failed to identify a set of traits that would distinguish effective from ineffective leaders, research attention turned to the study of leader behaviors. Leaders may demonstrate task-oriented and people- oriented behaviors. Both seem to be related to important outcomes, with task-oriented behaviors more strongly relating to leader effectiveness and people-oriented behaviors leading to employee satisfaction. Leaders can also make decisions using authoritarian, democratic, or laissez-faire styles. While laissez-faire has certain downsides, there is no best style, and the effectiveness of each style seems to vary across situations. Because of the inconsistency of results, researchers realized the importance of the context in which leadership occurs, which paved the way to contingency theories of leadership.

11.4 What Is the Role of the Context? Contingency Approaches to Leadership

What is the best leadership style? By now, you must have realized that this may not be the right question to ask. Instead, a better question might be: Under which conditions are certain leadership styles more effective? After the disappointing results of trait and behavioral approaches, several scholars developed leadership theories that specifically incorporated the role of the environment. Specifically, researchers started following a contingency approach to leadership—rather than trying to identify traits or behaviors that would be effective under all conditions, the attention moved toward specifying the situations under which different styles would be effective.

Fiedler’s Contingency Theory

The earliest and one of the most influential contingency theories was developed by Frederick Fiedler (Fiedler, 1967). According to the theory, a leader’s style is measured by a scale called Least Preferred Coworker scale (LPC). People who are filling out this survey are asked to think of a person who is their least preferred coworker. Then, they rate this person in terms of how friendly, nice, and cooperative this person is. Imagine someone you did not enjoy working with. Can you describe this person in positive terms? In other words, if you can say that the person you hated working with was still a nice person, you would have a high LPC score. This means that you have a people-oriented personality, and you can separate your liking of a person from your ability to work with that person. On the other hand, if you think that the person you hated working with was also someone you did not like on a personal level, you would have a low LPC score. To you, being unable to work with someone would mean that you also dislike that person. In other words, you are a task-oriented person.

According to Fiedler’s theory, different people can be effective in different situations. The LPC score is akin to a personality trait and is not likely to change. Instead, placing the right people in the right situation or changing the situation to suit an individual is important to increase a leader ’s effectiveness. The theory predicts that in “favorable” and “unfavorable” situations, a low LPC leader—one who has feelings of dislike for coworkers who are difficult to work with—would be successful. When situational favorableness is medium, a high LPC leader—one who is able to personally like coworkers who are difficult to work with—is more likely to succeed.

How does Fiedler determine whether a situation is “favorable,” “medium,” or “unfavorable”? There are three conditions creating situational favorableness: leader-subordinate relations, position power, and task structure. If the leader has a good relationship with most people and has high position power, and the task at hand is structured, the situation is very favorable. When the leader has low-quality relations with employees and has low position power, and the task at hand it relatively unstructured, the situation is very unfavorable.

Situational Favorableness

Situational favorableness |

Leader-subordinate relations |

Position Power |

Task structure |

Best Style |

|

Favorable |

Good | High | High |

Low LPC Leader |

| Good | High | Low | ||

| Good | Low | High | ||

|

Medium |

Good | Low | Low |

High LPC Leader |

| Poor | High | High | ||

| Poor | High | Low | ||

| Poor | Low | High | ||

| Unfavorable | Poor | Low | Low | Low LPC leader |

Sources: Based on information in Fiedler, F. E. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill; Fiedler, F. E. (1964). A contingency model of leader effectiveness. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, vol. 1 (pp. 149–190). New York: Academic Press.

Research partially supports the predictions of Fiedler’s contingency theory (Peters, Hartke, & Pohlmann, 1985; Strube & Garcia, 1981; Vecchio, 1983). Specifically, there is more support for the theory’s pre- dictions about when low LPC leadership should be used, but the part about when high LPC leadership would be more effective received less support. Even though the theory was not supported in its entirety, it is a useful framework to think about when task- versus people-oriented leadership may be more effective. Moreover, the theory is important because of its explicit recognition of the importance of the con- text of leadership.

Situational Leadership

Another contingency approach to leadership is Kenneth Blanchard and Paul Hersey’s Situational Leadership Theory (SLT) which argues that leaders must use different leadership styles depending on their followers’ development level (Hersey, Blanchard, & Johnson, 2007). According to this model, employee readiness (defined as a combination of their competence and commitment levels) is the key factor deter-mining the proper leadership style. This approach has been highly popular with 14 million managers across 42 countries undergoing SLT training and 70% of Fortune 500 companies employing its use.1

The model summarizes the level of directive and supportive behaviors that leaders may exhibit. The model argues that to be effective, leaders must use the right style of behaviors at the right time in each employee’s development. It is recognized that followers are key to a leader’s success. Employees who are at the earliest stages of developing are seen as being highly committed but with low competence for the tasks. Thus, leaders should be highly directive and less supportive. As the employee becomes more competent, the leader should engage in more coaching behaviors. Supportive behaviors are recommended once the employee is at moderate to high levels of competence. And finally, delegating is the recommended approach for leaders dealing with employees who are both highly committed and highly competent. While the SLT is popular with managers, relatively easy to understand and use, and has endured for decades, research has been mixed in its support of the basic assumptions of the model (Blank, Green, & Weitzel, 1990; Graeff, 1983; Fernandez & Vecchio, 2002). Therefore, while it can be a useful way to think about matching behaviors to situations, overreliance on this model, at the exclusion of other models, is premature.

Situational Leadership Theory helps leaders match their style to follower readiness levels.

|

Follower Readiness Level |

Competence (Low) | Competence (Low) | Competence (Moderate to High) | Competence (High) |

| Commitment (High) | Commitment (Low) | Commitment (Variable) | Commitment (High) | |

| Recommended Leader Style | Directing Behavior | Coaching Behavior | Supporting Behavior | Delegating Behavior |

Path-Goal Theory of Leadership

Robert House’s path-goal theory of leadership is based on the expectancy theory of motivation (House, 1971). The expectancy theory of motivation suggests that employees are motivated when they believe—or expect—that (a) their effort will lead to high performance, (b) their high performance will be rewarded, and (c) the rewards they will receive are valuable to them. According to the path-goal theory of leadership, the leader’s main job is to make sure that all three of these conditions exist. Thus, leaders will create satisfied and high-performing employees by making sure that employee effort leads to performance, and their performance is rewarded by desired rewards. The leader removes roadblocks along the way and creates an environment that subordinates find motivational.

The theory also makes specific predictions about what type of leader behavior will be effective under which circumstances (House, 1996; House & Mitchell, 1974). The theory identifies four leadership styles. Each of these styles can be effective, depending on the characteristics of employees (such as their ability level, preferences, locus of control, and achievement motivation) and characteristics of the work environment (such as the level of role ambiguity, the degree of stress present in the environment, and the degree to which the tasks are unpleasant).

Four Leadership Styles

Directive leaders provide specific directions to their employees. They lead employees by clarifying role expectations, setting schedules, and making sure that employees know what to do on a given work day. The theory predicts that the directive style will work well when employees are experiencing role ambiguity on the job. If people are unclear about how to go about doing their jobs, giving them specific directions will motivate them. On the other hand, if employees already have role clarity, and if they are performing boring, routine, and highly structured jobs, giving them direction does not help. In fact, it may hurt them by creating an even more restricting atmosphere. Directive leadership is also thought to be less effective when employees have high levels of ability. When managing professional employees with high levels of expertise and job-specific knowledge, telling them what to do may create a low- empowerment environment, which impairs motivation.

Supportive leaders provide emotional support to employees. They treat employees well, care about them on a personal level, and they are encouraging. Supportive leadership is predicted to be effective when employees are under a lot of stress or performing boring, repetitive jobs. When employees know exactly how to perform their jobs but their jobs are unpleasant, supportive leadership may be more effective.

Participative leaders make sure that employees are involved in the making of important decisions. Participative leadership may be more effective when employees have high levels of ability, and when the decisions to be made are personally relevant to them. For employees with a high internal locus of control (those who believe that they control their own destiny), participative leadership is a way of indirectly controlling organizational decisions, which is likely to be appreciated.

Achievement-oriented leaders set goals for employees and encourage them to reach their goals. Their style challenges employees and focuses their attention on work-related goals. This style is likely to be effective when employees have both high levels of ability and high levels of achievement motivation.

The path-goal theory of leadership has received partial but encouraging levels of support from researchers. Because the theory is highly complicated, it has not been fully and adequately tested (House & Aditya, 1997; Stinson & Johnson, 1975; Wofford & Liska, 1993). The theory’s biggest contribution may be that it highlights the importance of a leader’s ability to change styles depending on the circum- stances. Unlike Fiedler’s contingency theory, in which the leader’s style is assumed to be fixed and only the environment can be changed, House’s path-goal theory underlines the importance of varying one’s style depending on the situation.

Predictions of the Path-Goal Theory Approach to Leadership

Situation |

Appropriate Leadership Style |

|

• When employees have high role ambiguity • When employees have low abilities • When employees have external locus of control |

Directive |

|

• When tasks are boring and repetitive • When tasks are stressful |

Supportive |

|

• When employees have high abilities • When the decision is relevant to employees • When employees have high internal locus of control |

Participative |

|

• When employees have high abilities • When employees have high achievement motivation |

Achievement-oriented |

Sources: Based on information presented in House, R. J. (1996). Path-goal theory of leadership: Lessons, legacy, and a reformulated theory. Leadership Quarterly, 7, 323–352; House, R. J., & Mitchell, T. R. (1974). Path-goal theory of leadership. Journal of Contemporary Business, 3, 81–97.

Vroom and Yetton’s Normative Decision Model

Yale School of Management Professor Victor Vroom and his colleagues Philip Yetton and Arthur Jago developed a decision-making tool to help leaders determine how much involvement they should seek when making decisions (Vroom, 2000; Vroom & Yetton, 1973; Jago & Vroom, 1980; Vroom & Jago, 1988). The model starts by having leaders answer several key questions and working their way through a decision tree based on their responses. Let’s try it. Imagine that you want to help your employees lower their stress so that you can minimize employee absenteeism. There are a number of approaches you could take to reduce employee stress, such as offering gym memberships, providing employee assistance programs, a nap room, and so forth.

As you think about how to proceed, answer each question (below) as high (H) or low (L).

- Decision Significance. The decision has high significance, because the approach chosen needs to be effective at reducing employee stress for the insurance premiums to be lowered. In other words, there is a quality requirement to the decision. Follow the path through H.

- Importance of Commitment. Does the leader need employee cooperation to implement the decision? In our example, the answer is high, because employees may simply ignore the resources if they do not like them. Follow the path through H.

- Leader expertise. Does the leader have all the information needed to make a high quality decision? In our example, leader expertise is low. You do not have information regarding what your employees need or what kinds of stress reduction resources they would prefer. Follow the path through L.

- Likelihood of commitment. If the leader makes the decision alone, what is the likelihood that the employees would accept it? Let’s assume that the answer is low. Based on the leader’s experience with this group, they would likely ignore the decision if the leader makes it alone. Follow the path from L.

- Goal alignment. Are the employee goals aligned with organizational goals? In this instance, employee and organizational goals may be aligned because you both want to ensure that employees are healthier. So let’s say the alignment is high, and follow H.

- Group expertise. Does the group have expertise in this decision-making area? The group in question has little information about which alternatives are costlier, or more user friendly. We’ll say group expertise is low. Follow the path from L.

- Team competence. What is the ability of this particular team to solve the problem? Let’s imagine that this is a new team that just got together and they have little demonstrated expertise to work together effectively. We will answer this as low or L.

The normative approach recommends consulting employees as a group. In other words, the leader may make the decision alone after gathering information from employees and is not advised to delegate the decision to the team or to make the decision alone.

Decision-Making Styles

- Decide. The leader makes the decision alone using available information.

- Consult Individually. The leader obtains additional information from group members before making the decision alone.

- Consult as a group. The leader shares the problem with group members individually and makes the final decision alone.

- Facilitate. The leader shares information about the problem with group members collectively, and acts as a facilitator. The leader sets the parameters of the decision.

- Delegate. The leader lets the team make the decision.

Vroom and Yetton’s normative model is somewhat complicated, but research results support the validity of the model. On average, leaders using the style recommended by the model tend to make more effective decisions compared to leaders using a style not recommended by the model (Vroom & Jago, 1978).

Key Takeaway

The contingency approaches to leadership describe the role the situation would have in choosing the most effective leadership style. Fiedler’s contingency theory argued that task-oriented leaders would be most effective when the situation was the most and the least favorable, whereas people-oriented leaders would be effective when situational favorableness was moderate. Situational Leadership Theory takes the maturity level of followers into account. House’s path-goal theory states that the leader’s job is to ensure that employees view their effort as leading to performance, and to increase the belief that performance would be rewarded. For this purpose, leaders would use directive-, supportive-, participative-, and achievement-oriented leadership styles depending on what employees needed to feel motivated. Vroom and Yetton’s normative model is a guide leaders can use to decide how participative they should be given decision environment characteristics.

11.5 What’s New? Contemporary Approaches to Leadership

What are the leadership theories that have the greatest contributions to offer to today’s business environment? In this section, we will review the most recent developments in the field of leadership.

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership theory is a recent addition to the literature, but more research has been con- ducted on this theory than all the contingency theories combined. The theory distinguishes transformational and transactional leaders. Transformational leaders lead employees by aligning employee goals with the leader’s goals. Thus, employees working for transformational leaders start focusing on the company’s well-being rather than on what is best for them as individual employees. On the other hand, transactional leaders ensure that employees demonstrate the right behaviors and provide resources in exchange (Bass, 1985; Burns, 1978).

Transformational leaders have four tools in their possession, which they use to influence employees and create commitment to the company goals (Bass, 1985; Burns, 1978; Bycio, Hackett, & Allen, 1995; Judge & Piccolo, 2004). First, transformational leaders are charismatic. Charisma refers to behaviors leaders demonstrate that create confidence in, commitment to, and admiration for the leader (Shamir, House, & Arthur, 1993). Charismatic individuals have a “magnetic” personality that is appealing to followers. Second, transformational leaders use inspirational motivation, or come up with a vision that is inspiring to others. Third is the use of intellectual stimulation, which means that they challenge organizational norms and status quo, and they encourage employees to think creatively and work harder. Finally, they use individualized consideration, which means that they show personal care and concern for the well-being of their followers. Examples of transformational leaders include Steve Jobs of Apple Inc.; Lee Iaccoca, who transformed Chrysler Motors LLC in the 1980s; and Jack Welch, who was the CEO of General Electric Company for 20 years. Each of these leaders is charismatic and is held responsible for the turnarounds of their companies.

While transformational leaders rely on their charisma, persuasiveness, and personal appeal to change and inspire their companies, transactional leaders use three different methods. Contingent rewards mean rewarding employees for their accomplishments. Active management by exception involves leaving employees to do their jobs without interference, but at the same time proactively predicting potential problems and preventing them from occurring. Passive management by exception is similar in that it involves leaving employees alone, but in this method the manager waits until something goes wrong before coming to the rescue.

Which leadership style do you think is more effective, transformational or transactional? Research shows that transformational leadership is a very powerful influence over leader effectiveness as well as employee satisfaction (Judge & Piccolo, 2004). In fact, transformational leaders increase the intrinsic motivation of their followers, build more effective relationships with employees, increase performance and creativity of their followers, increase team performance, and create higher levels of commitment to organizational change efforts (Herold et al., 2008; Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006; Schaubroeck, Lam, & Cha, 2007; Shin & Zhou, 2003; Wang et al., 2005). However, except for passive management by exception, the transactional leadership styles are also effective, and they also have positive influences over leader performance as well as employee attitudes (Judge & Piccolo, 2004). To maximize their effectiveness, leaders are encouraged to demonstrate both transformational and transactional styles. They should also monitor themselves to avoid demonstrating passive management by exception, or leaving employees to their own devices until problems arise.

Why is transformational leadership effective? The key factor may be trust. Trust is the belief that the leader will show integrity, fairness, and predictability in his or her dealings with others. Research shows that when leaders demonstrate transformational leadership behaviors, followers are more likely to trust the leader. The tendency to trust in transactional leaders is substantially lower. Because transformational leaders express greater levels of concern for people’s well-being and appeal to people’s values, followers are more likely to believe that the leader has a trustworthy character (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002).

Is transformational leadership genetic? Some people assume that charisma is something people are born with. You either have charisma, or you don’t. However, research does not support this idea. We must acknowledge that there is a connection between some personality traits and charisma. Specifically, people who have a neurotic personality tend to demonstrate lower levels of charisma, and people who are extraverted tend to have higher levels of charisma. However, personality explains only around 10% of the variance in charisma (Bono & Judge, 2004). A large body of research has shown that it is possible to train people to increase their charisma and increase their transformational leadership (Barling, Weber, & Kelloway, 1996; Dvir et al., 2002; Frese, Beimel, & Schoenborg, 2003).

Even if charisma can be learned, a more fundamental question remains: Is it really needed? Charisma is only one element of transformational leadership, and leaders can be effective without charisma. In fact, charisma has a dark side. For every charismatic hero such as Lee Iaccoca, Steve Jobs, and Virgin Atlantic Airways Ltd.’s Sir Richard Branson, there are charismatic personalities who harmed their organizations or nations, such as Adoph Hitler of Germany and Jeff Skilling of Enron Corporation. Leadership experts warn that when organizations are in a crisis, a board of directors or hiring manager may turn to heroes who they hope will save the organization, and sometimes hire people who have no particular qualifications other than being perceived as charismatic (Khurana, 2002).

An interesting study shows that when companies have performed well, their CEOs are perceived as charismatic, but CEO charisma has no relation to the future performance of a company (Agle et al., 2006). So, what we view as someone’s charisma may be largely because of their association with a successful company, and the success of a company depends on a large set of factors, including industry effects and historical performance. While it is true that charismatic leaders may sometimes achieve great results, the search for charismatic leaders under all circumstances may be irrational.

Toolbox: Be Charismatic!

- Have a vision around which people can gather. When framing requests or addressing others, instead of emphasizing short-term goals, stress the importance of the long-term vision. When giving a message, think about the overarching purpose. What is the ultimate goal? Why should people care? What are you trying to achieve?

- Tie the vision to history. In addition to stressing the ideal future, charismatic leaders also bring up the history and how the shared history ties to the future.

- Watch your body language. Charismatic leaders are energetic and passionate about their ideas. This involves truly believing in your own ideas. When talking to others, be confident, look them in the eye, and express your belief in your ideas.

- Make sure that employees have confidence in themselves. You can achieve this by showing that you believe in them and trust in their abilities. If they have real reason to doubt their abilities, make sure that you address the underlying issue, such as training and mentoring.

- Challenge the status quo. Charismatic leaders solve current problems by radically rethinking the way things are done and suggesting alternatives that are risky, novel, and unconventional.

Sources: Adapted from ideas in Frese, M., Beimel, S., & Schoenborg, S. (2003). Action training for charismatic leadership: Two evaluations of studies of a commercial training module on inspirational communication of a vision. Personnel Psychology, 56, 671–697; Shamir, B., House, R. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1993). The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organization Science, 4, 577–594.

Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory

Leader-member exchange (LMX) theory proposes that the type of relationship leaders have with their followers (members of the organization) is the key to understanding how leaders influence employees. Leaders form different types of relationships with their employees. In high-quality LMX relationships, the leader forms a trust-based relationship with the member. The leader and member like each other, help each other when needed, and respect each other. In these relationships, the leader and the member are each ready to go above and beyond their job descriptions to promote the other’s ability to succeed. In contrast, in low-quality LMX relationships, the leader and the member have lower levels of trust, liking, and respect toward each other. These relationships do not have to involve actively disliking each other, but the leader and member do not go beyond their formal job descriptions in their exchanges. In other words, the member does his job, the leader provides rewards and punishments, and the relation- ship does not involve high levels of loyalty or obligation toward each other (Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, 1975; Erdogan & Liden, 2002; Gerstner & Day, 1997; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Liden & Maslyn, 1998).

If you have work experience, you may have witnessed the different types of relationships managers form with their employees. In fact, many leaders end up developing differentiated relationships with their followers. Within the same work group, they may have in-group members who are close to them, and out-group members who are more distant. If you have ever been in a high LMX relationship with your manager, you may attest to the advantages of the relationship. Research shows that high LMX members are more satisfied with their jobs, more committed to their companies, have higher levels of clarity about what is expected of them, and perform at a higher level (Gerstner & Day, 1997; Hui, Law, & Chen, 1999; Kraimer, Wayne, & Jaworski, 2001; Liden, Wayne, & Sparrowe, 2000; Settoon, Bennett, & Liden, 1996; Tierney, Farmer, & Graen, 1999; Wayne, Shore, & Liden, 1997). Employees’ high levels of performance may not be a surprise, since they receive higher levels of resources and help from their managers as well as more information and guidance. If they have questions, these employees feel more comfortable seeking feedback or information (Chen, Lam, & Zhong, 2007). Because of all the help, support, and guidance they receive, employees who have a good relationship with the manager are in a better position to perform well. Given all they receive, these employees are motivated to reciprocate to the manager, and therefore they demonstrate higher levels of citizenship behaviors such as helping the leader and coworkers (Ilies, Nahrgang, & Morgeson, 2007). Being in a high LMX relationship is also advantageous because a high-quality relationship is a buffer against many stressors, such as being a misfit in a company, having personality traits that do not match job demands, and having unmet expectations (Bauer et al., 2006; Erdogan, Kraimer, & Liden, 2004; Major et al., 1995).The list of the benefits high LMX employees receive is long, and it is not surprising that these employees are less likely to leave their jobs (Ferris, 1985; Graen, Liden, & Hoel, 1982).

The problem, of course, is that not all employees have a high-quality relationship with their leader, and those who are in the leader’s out-group may suffer as a result. But how do you develop a high-quality relationship with your leader? It seems that this depends on many factors. Managers can help develop such a meaningful and trust-based relationship by treating their employees in a fair and dignified manner (Masterson et al., 2002). They can also test to see if the employee is trustworthy by delegating certain tasks when the employee first starts working with the manager (Bauer & Green, 1996). Employees also have an active role in developing the relationship. Employees can put forth effort into developing a good relationship by seeking feedback to improve their performance, being open to learning new things on the job, and engaging in political behaviors such as the use of flattery (Colella & Varma, 2001; Maslyn & Uhl-Bien, 2001; Janssen & Van Yperen, 2004; Wing, Xu & Snape, 2007). Interestingly, high performance does not seem to be enough to develop a high-quality exchange. Instead, interpersonal factors such as the similarity of personalities and a mutual liking and respect are more powerful influences over how the relationship develops (Engle & Lord, 1997; Liden, Wayne, & Stilwell, 1993; Wayne, Shore, & Liden, 1997). Finally, the relationship develops differently in different types of companies, and corporate culture matters in how leaders develop these relationships. In performance-oriented cultures, the relevant factor seems to be how the leader distributes rewards, whereas in people-oriented cultures, the leader treating people with dignity is more important (Erdogan, Liden, & Kraimer, 2006).

Self-Assessment: Rate Your LMX

Answer the following questions using 1 = not at all, 2 = somewhat, 3 = fully agree.

| 1. | I like my supervisor very much as a person. | |

| 2. | My supervisor is the kind of person one would like to have as a friend. | |

| 3. | My supervisor is a lot of fun to work with. | |

| 4. | My supervisor defends my work actions to a superior, even without complete knowledge of the issue in question. |

| 5. | My supervisor would come to my defense if I were “attacked” by others. | |

| 6. | My supervisor would defend me to others in the organization if I made an honest mistake. | |

| 7. | I do work for my supervisor that goes beyond what is specified in my job description. | |

| 8. | I am willing to apply extra efforts, beyond those normally required, to further the interests of my work group. |

| 9. | I do not mind working my hardest for my supervisor. | |

| 10. | I am impressed with my supervisor’s knowledge of his or her job. | |

| 11. | I respect my supervisor’s knowledge of and competence on the job. | |

| 12. | I admire my supervisor’s professional skills. |

Scoring:

Add your score for 1, 2, 3 =

This is your score on the Liking factor of LMX.

A score of 3 to 4 indicates a low LMX in terms of liking. A score of 5 to 6 indicates an average LMX in terms of liking. A score of 7+ indicates a high LMX in terms of liking.

Add your score for 4, 5, 6 = This is your score on the Loyalty factor of LMX.

A score of 3 to 4 indicates a low LMX in terms of loyalty. A score of 5 to 6 indicates an average LMX in terms of loyalty. A score of 7+ indicates a high LMX in terms of loyalty.

Add your score for 7, 8, 9 = . This is your score on the Contribution factor of LMX.

A score of 3 to 4 indicates a low LMX in terms of contribution. A score of 5 to 6 indicates an average LMX in terms of contribution. A score of 7+ indicates a high LMX in terms of contribution.

Add your score for 10, 11, 12 = . This is your score on the Professional Respect factor of LMX.

A score of 3 to 4 indicates a low LMX in terms of professional respect. A score of 5 to 6 indicates an average LMX in terms of professional respect. A score of 7+ indicates a high LMX in terms of professional respect.

Source: Adapted from Liden, R. C., & Maslyn, J. M. (1998). Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. Journal of Management, 24, 43–72. Used by permission of Sage Publications.

Should you worry if you do not have a high-quality relationship with your manager? One problem in a low-quality exchange is that employees may not have access to the positive work environment available to high LMX members. Secondly, low LMX employees may feel that their situation is unfair. Even when their objective performance does not warrant it, those who have a good relationship with the leader tend to have positive performance appraisals (Duarte, Goodson, & Klich, 1994). Moreover, they are more likely to be given the benefit of the doubt. For example, when high LMX employees succeed, the man- ager is more likely to think that they succeeded because they put forth a lot of effort and had high abilities, whereas for low LMX members who perform objectively well, the manager is less likely to make the same attribution (Heneman, Greenberger, & Anonyuo, 1989). In other words, the leader may interpret the same situation differently, depending on which employee is involved, and may reward low LMX employees less despite equivalent performance. In short, those with a low-quality relationship with their leader may experience a work environment that may not be supportive or fair.

Despite its negative consequences, we cannot say that all employees want to have a high-quality relationship with their leader. Some employees may genuinely dislike the leader and may not value the rewards in the leader’s possession. If the leader is not well liked in the company and is known as abusive or unethical, being close to such a person may imply guilt by association. For employees who have no interest in advancing their careers in the current company (such as a student employee who is working in retail but has no interest in retail as a career), having a low-quality exchange may afford the opportunity to just do one’s job without having to go above and beyond the job requirements. Finally, not all leaders are equally capable of influencing their employees by having a good relationship with them: It also depends on the power and influence of the leader in the company as a whole and how the leader is treated within the organization. Leaders who are more powerful will have more to share with their employees (Erdogan & Enders, 2007; Sparrowe & Liden, 2005; Tangirala, Green, & Ramanujam, 2007).

What LMX theory implies for leaders is that one way of influencing employees is through the types of relationships leaders form with their subordinates. These relationships develop naturally through the work-related and personal interactions between the manager and the employee. Because they occur naturally, some leaders may not be aware of the power that lies in them. These relationships have an important influence over employee attitudes and behaviors. In the worst case, they have the potential to create an environment characterized by favoritism and unfairness. Therefore, managers are advised to be aware of how they build these relationships: Put forth effort in cultivating these relationships consciously, be open to forming good relationships with people from all backgrounds regardless of characteristics such as sex, race, age, or disability status, and prevent these relationships from leading to an unfair work environment.

Toolbox: Ideas for Improving Your Relationship With Your Manager

Having a good relationship with your manager may substantially increase your job satisfaction, improve your ability to communicate with your manager, and help you be successful in your job. Here are some tips to developing a high-quality exchange.

- Create interaction opportunities with your manager. One way of doing this would be seeking feedback from your manager with the intention of improving your performance. Be careful though: If the manager believes that you are seeking feedback for a different purpose, it will not help.

- People are more attracted to those who are similar to them. So find out where your similarities lie. What does your manager like that you also like? Do you have similar working styles? Do you have any mutual experiences? Bringing up your commonalities in conversations may help.

- Utilize impression management tactics, but be tactful. If there are work-related areas in which you can sincerely compliment your manager, do so. For example, if your manager made a decision that you agree with, you may share your support. Most people, including managers, appreciate positive feedback. However, flattering your manager in non-work-related areas (such as appearance) or using flattery in an insincere way (praising an action you do not agree with) will only backfire and cause you to be labeled as a flatterer.

- Be a reliable employee. Managers need people they can trust. By performing at a high level, demonstrating predictable and consistent behavior, and by volunteering for challenging assignments, you can prove your worth.

- Be aware that relationships develop early (as early as the first week of your working together). So be careful how you behave during the interview and your very first days. If you rub your manager the wrong way early on, it will be harder to recover the relationship.

Sources: Based on information presented in Colella, A., & Varma, A. (2001). The impact of subordinate dis- ability on leader-member exchange relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 304–315; Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Stilwell, D. (1993). A longitudinal study on the early development of leader-member exchanges. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 662–674; Maslyn, J. M., & Uhl-Bien, M. (2001). Leader- member exchange and its dimensions: Effects of self-effort and other’s effort on relationship quality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 697–708; Wing, L., Xu, H., & Snape, E. (2007). Feedback-seeking behavior and leader-member exchange: Do supervisor-attributed motives matter? Academy of Management Journal, 50, 348–363.

Servant Leadership

The early 21st century has been marked by a series of highly publicized corporate ethics scandals: Between 2000 and 2003 we witnessed the scandals of Enron, WorldCom, Arthur Andersen LLP, Qwest Communications International Inc., and Global Crossing Ltd. As corporate ethics scandals shake investor confidence in corporations and leaders, the importance of ethical leadership and keeping long- term interests of stakeholders in mind is becoming more widely acknowledged.

Servant leadership is a leadership approach that defines the leader’s role as serving the needs of others. According to this approach, the primary mission of the leader is to develop employees and help them reach their goals. Servant leaders put their employees first, understand their personal needs and desires, empower them, and help them develop in their careers. Unlike mainstream management approaches, the overriding objective in servant leadership is not limited to getting employees to contribute to organizational goals. Instead, servant leaders feel an obligation to their employees, customers, and the external community. Employee happiness is seen as an end in itself, and servant leaders sometimes sacrifice their own well-being to help employees succeed. In addition to a clear focus on having a moral compass, servant leaders are also interested in serving the community. In other words, their efforts to help others are not restricted to company insiders, and they are genuinely concerned about the broader community sur- rounding their organization (Greenleaf, 1977; Liden et al., 2008). According to historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, Abraham Lincoln was a servant leader because of his balance of social conscience, empathy, and generosity (Goodwin, 2005).

Even though servant leadership has some overlap with other leadership approaches such as transformational leadership, its explicit focus on ethics, community development, and self-sacrifice are distinct characteristics of this leadership style. Research shows that servant leadership has a positive impact on employee commitment, employee citizenship behaviors toward the community (such as participating in community volunteering), and job performance (Liden et al., 2008). Leaders who follow the servant leadership approach create a climate of fairness in their departments, which leads to higher levels of interpersonal helping behavior (Ehrhart, 2004).

Servant leadership is a tough transition for many managers who are socialized to put their own needs first, be driven by success, and tell people what to do. In fact, many of today’s corporate leaders are not known for their humility! However, leaders who have adopted this approach attest to its effectiveness. David Wolfskehl, of Action Fast Print in New Jersey, founded his printing company when he was 24 years old. He marks the day he started asking employees what he can do for them as the beginning of his company’s new culture. In the next 2 years, his company increased its productivity by 30% (Buchanan, 2007).

Toolbox: Be a Servant Leader

One of the influential leadership paradigms involves leaders putting others first. This could be a hard transition for an achievement-oriented and success-driven manager who rises to high levels. Here are some tips to achieve servant leadership.

- Don’t ask what your employees can do for you. Think of what you can do for them. Your job as a leader is to be of service to them. How can you relieve their stress? Protect them from undue pressure? Pitch in to help them? Think about creative ways of helping ease their lives.

- One of your key priorities should be to help employees reach their goals. This involves getting to know them. Learn about who they are and what their values and priorities are.

- Be humble. You are not supposed to have all the answers and dictate others. One way of achieving this humbleness may be to do volunteer work.

- Be open with your employees. Ask them questions. Give them information so that they understand what is going on in the company.

- Find ways of helping the external community. Giving employees opportunities to be involved in community volunteer projects or even thinking and strategizing about making a positive impact on the greater community would help.

Sources: Based on information presented in Buchanan, L. (2007, May). In praise of selflessness: Why the best leaders are servants. Inc, 29(5), 33–35; Douglas, M. E. (2005, March). Service to others. Supervision, 66(3), 6–9; Ramsey, R. D. (2005, October). The new buzz word. Supervision, 66(10), 3–5.

Authentic Leadership

Leaders have to be a lot of things to a lot of people. They operate within different structures, work with different types of people, and they have to be adaptable. At times, it may seem that a leader’s smartest strategy would be to act as a social chameleon, changing his or her style whenever doing so seems advantageous. But this would lose sight of the fact that effective leaders have to stay true to themselves. The authentic leadership approach embraces this value: Its key advice is “be yourself.” Think about it: We all have different backgrounds, different life experiences, and different role models. These trigger events over the course of our lifetime that shape our values, preferences, and priorities. Instead of trying to fit into societal expectations about what a leader should be, act like, or look like, authentic leaders derive their strength from their own past experiences. Thus, one key characteristic of authentic leaders is that they are self aware. They are introspective, understand where they are coming from, and have a thorough understanding of their own values and priorities. Secondly, they are not afraid to act the way they are. In other words, they have high levels of personal integrity. They say what they think. They behave in a way consistent with their values. As a result, they remain true to themselves. Instead of trying to imitate other great leaders, they find their own style in their personality and life experiences (Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Gardner et al., 2005; George, 2007; Ilies, Morgeson, & Nahrgang, 2005; Sparrowe, 2005).

One example of an authentic leader is Howard Schultz, the founder of Starbucks Corporation coffee- houses. As a child, Schultz witnessed the job-related difficulties his father experienced as a result of medical problems. Even though he had no idea he would have his own business one day, the desire to protect people was shaped in those years and became one of his foremost values. When he founded Star- bucks, he became an industry pioneer by providing health insurance and retirement coverage to part-time as well as full-time employees (Shamir & Eilam, 2005).

Authentic leadership requires understanding oneself. Therefore, in addition to self reflection, feedback from others is needed to gain a true understanding of one’s behavior and its impact on others. Authentic leadership is viewed as a potentially influential style, because employees are more likely to trust such a leader. Moreover, working for an authentic leader is likely to lead to greater levels of satisfaction, performance, and overall well-being on the part of employees (Walumbwa et al., 2008).

Key Takeaway

Contemporary approaches to leadership include transformational leadership, leader-member exchange, servant leadership, and authentic leadership. The transformational leadership approach highlights the importance of leader charisma, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration as methods of influence. Its counterpart is the transactional leadership approach, in which the leader focuses on getting employees to achieve organizational goals. According to the leader-member exchange (LMX) approach, the unique, trust-based relationships leaders develop with employees are the key to leadership effectiveness. Recently, leadership scholars started to emphasize the importance of serving others and adopting a customer-oriented view of leadership; another recent focus is on the importance of being true to oneself as a leader. While each leadership approach focuses on a different element of leadership, effective leaders will need to change their style based on the demands of the situation, as well as utilizing their own values and moral compass.

11.6 The Role of Ethics and National Culture

Leadership and Ethics

As some organizations suffer the consequences of ethical crises that put them out of business or damage their reputations, the role of leadership as a driver of ethical behavior is receiving a lot of scholarly attention as well as acknowledgement in the popular press. Ethical decisions are complex and, even to people who are motivated to do the right thing, the moral component of a decision may not be obvious. Therefore, employees often look to role models, influential people, and their managers for guidance in how to behave. Unfortunately, research shows that people tend to follow leaders or other authority figures even when doing so can put others at risk. The famous Milgram experiments support this point. Milgram conducted experiments in which experimental subjects were greeted by someone in a lab coat and asked to administer electric shocks to other people who gave the wrong answer in a learning task. In fact, the shocks were not real and the learners were actors who expressed pain when shocks were administered. Around two-thirds of the experimental subjects went along with the requests and administered the shocks even after they reached what the subjects thought were dangerous levels. In other words, people in positions of authority are influential in driving others to ethical or unethical behaviors (Milgram, 1974; Trevino & Brown, 2004).

It seems that when evaluating whether someone is an effective leader, subordinates pay attention to the level of ethical behaviors the leader demonstrates. In fact, one study indicated that the perception of being ethical explained 10% of the variance in whether an individual was also perceived as a leader. The level of ethical leadership was related to job satisfaction, dedication to the leader, and a willingness to report job-related problems to the leader (Brown, Trevino, & Harrison, 2005; Morgan, 1993).

Leaders influence the level of ethical behaviors demonstrated in a company by setting the tone of the organizational climate. Leaders who have high levels of moral development create a more ethical organizational climate (Schminke, Ambrose, & Neubaum, 2005). By acting as a role model for ethical behavior, rewarding ethical behaviors, publicly punishing unethical behaviors, and setting high expectations for the level of ethics, leaders play a key role in encouraging ethical behaviors in the workplace.

The more contemporary leadership approaches are more explicit in their recognition that ethics is an important part of effective leadership. Servant leadership emphasizes the importance of a large group of stakeholders, including the external community surrounding a business. On the other hand, authentic leaders have a moral compass, they know what is right and what is wrong, and they have the courage to follow their convictions. Research shows that transformational leaders tend to have higher levels of moral reasoning, even though it is not part of the transformational leadership theory (Turner et al., 2002). It seems that ethical behavior is more likely to happen when (a) leaders are ethical themselves, and (b) they create an organizational climate in which employees understand that ethical behaviors are desired, valued, and expected.

Leadership Around the Globe

Is leadership universal? This is a critical question given the amount of international activity in the world. Companies that have branches in different countries often send expatriates to manage the operations. These expatriates are people who have demonstrated leadership skills at home, but will these same skills work in the host country? Unfortunately, this question has not yet been fully answered. All the leadership theories that we describe in this chapter are U.S.-based. Moreover, around 98% of all leadership research has been conducted in the United States and other western nations. Thus, these leadership theories may have underlying cultural assumptions. The United States is an individualistic, performance-oriented culture, and the leadership theories suitable for this culture may not necessarily be suitable to other cultures.

People who are perceived as leaders in one society may have different traits compared to people perceived as leaders in a different culture, because each society has a concept of ideal leader prototypes. When we see certain characteristics in a person, we make the attribution that this person is a leader. For example, someone who is confident, caring, and charismatic may be viewed as a leader because we feel that these characteristics are related to being a leader. These leadership prototypes are societally driven and may have a lot to do with a country’s history and its heroes.

Recently, a large group of researchers from 62 countries came together to form a project group called Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness or GLOBE (House et al., 2004). This group is one of the first to examine leadership differences around the world. Their results are encouraging, because, in addition to identifying differences, they found similarities in leadership styles as well. Specifically, certain leader traits seem to be universal. Around the world, people feel that honesty, decisiveness, being trustworthy, and being fair are related to leadership effectiveness. There is also universal agreement in characteristics viewed as undesirable in leaders: being irritable, egocentric, and a loner (Den Hartog et al., 1999; Javidan et al., 2006). Visionary and charismatic leaders were found to be the most influential leaders around the world, followed by team-oriented and participative leaders. In other words, there seems to be a substantial generalizability in some leadership styles.

Even though certain leader behaviors such as charismatic or supportive leadership appear to be universal, what makes someone charismatic or supportive may vary across nations. For example, when leaders fit the leadership prototype, they tend to be viewed as charismatic, but in Turkey, if they are successful but did not fit the prototype, they were still viewed as charismatic (Ensari & Murphy, 2003). In Western and Latin cultures, people who speak in an emotional and excited manner may be viewed as charismatic. In Asian cultures such as China and Japan, speaking in a monotonous voice may be more impressive because it shows that the leader can control emotions. Similarly, how leaders build relationships or act supportively is culturally determined. In collectivist cultures such as Turkey or Mexico, a manager is expected to show personal interest in employees’ lives. Visiting an employee’s sick mother at the hospital may be a good way of showing concern. Such behavior would be viewed as intrusive or strange in the United States or the Netherlands. Instead, managers may show concern verbally or by lightening the workload of the employee (Brodbeck et al., 2000; Den Hartog et al., 1999).