Chapter 6: Managing Groups and Teams

Managing Groups and Teams

9.1 Teamwork Takes to the Sky: The Case of General Electric

In Durham, North Carolina, Robert Henderson was opening a factory for General Electric Company (NYSE: GE). The goal of the factory was to manufacture the largest commercial jet engine in the world. Henderson’s opportunity was great and so were his challenges. GE hadn’t designed a jet engine from the ground up for over 2 decades. Developing the jet engine project had already cost GE $1.5 billion. That was a huge sum of money to invest—and an unacceptable sum to lose should things go wrong in the manufacturing stage.

How could one person fulfill such a vital corporate mission? The answer, Henderson decided, was that one person couldn’t fulfill the mission. Even Jack Welch, GE’s CEO at the time, said, “We now know where productivity comes from. It comes from challenged, empowered, excited, rewarded teams of people.”

Empowering factory workers to contribute to GE’s success sounded great in theory. But how to accomplish these goals in real life was a more challenging question. Factory floors, traditionally, are unempowered work- places where workers are more like cogs in a vast machine than self-determining team members.

In the name of teamwork and profitability, Henderson traveled to other factories looking for places where worker autonomy was high. He implemented his favorite ideas at the factory at Durham. Instead of hiring generic “mechanics,” for example, Henderson hired staffers with FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) mechanic’s licenses. This superior training created a team capable of making vital decisions with minimal oversight, a fact that upped the factory’s output and his workers’ feelings of worth.

Henderson’s “self-managing” factory functioned beautifully. And it looked different, too. Plant manager Jack Fish described Henderson’s radical factory, saying Henderson “didn’t want to see supervisors, he didn’t want to see forklifts running all over the place, he didn’t even want it to look traditional. There’s clutter in most plants, racks of parts and so on. He didn’t want that.”

Henderson also contracted out non-job-related chores, such as bathroom cleaning, that might have been assigned to workers in traditional factories. His insistence that his workers should contribute their highest talents to the team showed how much he valued them. And his team valued their jobs in turn.

Six years later, a Fast Company reporter visiting the plant noted, “GE/Durham team members take such pride in the engines they make that they routinely take brooms in hand to sweep out the beds of the 18-wheelers that transport those engines—just to make sure that no damage occurs in transit.” For his part, Henderson, who remained at GE beyond the project, noted, “I was just constantly amazed by what was accomplished there.”

GE’s bottom line showed the benefits of teamwork, too. From the early 1980s, when Welch became CEO, until 2000, when he retired, GE generated more wealth than any organization in the history of the world.

Based on information from Fishman, C. (1999, September). How teamwork took flight. Fast Company. Retrieved August 1, 2008, from http://www.fastcompany.com/node/38322/print; Lear, R. (1998, July–August). Jack Welch speaks: Wisdom from the world’s greatest business leader. Chief Executive; Guttman, H. (2008, January–February). Leading high-performance teams: Horizontal, high-performance teams with real decision-making clout and accountability for results can transform a company. Chief Executive, pp. 231–233.

9.2 Group Dynamics

Types of Groups: Formal and Informal

What is a group? A group is a collection of individuals who interact with each other such that one per- son’s actions have an impact on the others. In organizations, most work is done within groups. How groups function has important implications for organizational productivity. Groups where people get along, feel the desire to contribute to the team, and are capable of coordinating their efforts may have high performance levels, whereas teams characterized by extreme levels of conflict or hostility may demoralize members of the workforce.

In organizations, you may encounter different types of groups. Informal work groups are made up of two or more individuals who are associated with one another in ways not prescribed by the formal organization. For example, a few people in the company who get together to play tennis on the weekend would be considered an informal group. A formal work group is made up of managers, subordinates, or both with close associations among group members that influence the behavior of individuals in the group. We will discuss many different types of formal work groups later on in this chapter.

Stages of Group Development

Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing

American organizational psychologist Bruce Tuckman presented a robust model in 1965 that is still widely used today. Based on his observations of group behavior in a variety of settings, he proposed a four-stage map of group evolution, also known as the forming-storming-norming-performing model (Tuckman, 1965). Later he enhanced the model by adding a fifth and final stage, the adjourning phase. Interestingly enough, just as an individual moves through developmental stages such as childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, so does a group, although in a much shorter period of time. According to this theory, in order to successfully facilitate a group, the leader needs to move through various leadership styles over time. Generally, this is accomplished by first being more directive, eventually serving as a coach, and later, once the group is able to assume more power and responsibility for itself, shifting to a delegator. While research has not confirmed that this is descriptive of how groups progress, knowing and following these steps can help groups be more effective. For example, groups that do not go through the storming phase early on will often return to this stage toward the end of the group process to address unresolved issues. Another example of the validity of the group development model involves groups that take the time to get to know each other socially in the forming stage. When this occurs, groups tend to handle future challenges better because the individuals have an understanding of each other’s needs.

Forming

In the forming stage, the group comes together for the first time. The members may already know each other or they may be total strangers. In either case, there is a level of formality, some anxiety, and a degree of guardedness as group members are not sure what is going to happen next. “Will I be accepted? What will my role be? Who has the power here?” These are some of the questions participants think about during this stage of group formation. Because of the large amount of uncertainty, members tend to be polite, conflict avoidant, and observant. They are trying to figure out the “rules of the game” with- out being too vulnerable. At this point, they may also be quite excited and optimistic about the task at hand, perhaps experiencing a level of pride at being chosen to join a particular group. Group members are trying to achieve several goals at this stage, although this may not necessarily be done consciously. First, they are trying to get to know each other. Often this can be accomplished by finding some common ground. Members also begin to explore group boundaries to determine what will be considered accept- able behavior. “Can I interrupt? Can I leave when I feel like it?” This trial phase may also involve testing the appointed leader or seeing if a leader emerges from the group. At this point, group members are also discovering how the group will work in terms of what needs to be done and who will be responsible for each task. This stage is often characterized by abstract discussions about issues to be addressed by the group; those who like to get moving can become impatient with this part of the process. This phase is usually short in duration, perhaps a meeting or two.

Storming

Once group members feel sufficiently safe and included, they tend to enter the storming phase. Participants focus less on keeping their guard up as they shed social facades, becoming more authentic and more argumentative. Group members begin to explore their power and influence, and they often stake out their territory by differentiating themselves from the other group members rather than seeking common ground. Discussions can become heated as participants raise contending points of view and values, or argue over how tasks should be done and who is assigned to them. It is not unusual for group members to become defensive, competitive, or jealous. They may even take sides or begin to form cliques within the group. Questioning and resisting direction from the leader is also quite common. “Why should I have to do this? Who designed this project in the first place? Why do I have to listen to you?” Although little seems to get accomplished at this stage, group members are becoming more authentic as they express their deeper thoughts and feelings. What they are really exploring is “Can I truly be me, have power, and be accepted?” During this chaotic stage, a great deal of creative energy that was previously buried is released and available for use, but it takes skill to move the group from storming to norming. In many cases, the group gets stuck in the storming phase.

Toolbox: Avoid Getting Stuck in the Storming Phase!

There are several steps you can take to avoid getting stuck in the storming phase of group development. Try the following if you feel the group process you are involved in is not progressing:

- Normalize conflict. Let members know this is a natural phase in the group-formation process.

- Be inclusive. Continue to make all members feel included and invite all views into the room. Mention how diverse ideas and opinions help foster creativity and innovation.

- Make sure everyone is heard. Facilitate heated discussions and help participants understand each other.

- Support all group members. This is especially important for those who feel more insecure.

- Remain positive. This is a key point to remember about the group’s ability to accomplish its goal.

- Don’t rush the group’s development. Remember that working through the storming stage can take several meetings.

Once group members discover that they can be authentic and that the group is capable of handling differences without dissolving, they are ready to enter the next stage, norming.

Norming

“We survived!” is the common sentiment at the norming stage. Group members often feel elated at this point, and they are much more committed to each other and the group’s goal. Feeling energized by knowing they can handle the “tough stuff,” group members are now ready to get to work. Finding them- selves more cohesive and cooperative, participants find it easy to establish their own ground rules (or norms) and define their operating procedures and goals. The group tends to make big decisions, while subgroups or individuals handle the smaller decisions. Hopefully, at this point the group is more open and respectful toward each other, and members ask each other for both help and feedback. They may even begin to form friendships and share more personal information with each other. At this point, the leader should become more of a facilitator by stepping back and letting the group assume more responsibility for its goal. Since the group’s energy is running high, this is an ideal time to host a social or team-building event.

Performing

Galvanized by a sense of shared vision and a feeling of unity, the group is ready to go into high gear. Members are more interdependent, individuality and differences are respected, and group members feel themselves to be part of a greater entity. At the performing stage, participants are not only getting the work done, but they also pay greater attention to how they are doing it. They ask questions like, “Do our operating procedures best support productivity and quality assurance? Do we have suitable means for addressing differences that arise so we can preempt destructive conflicts? Are we relating to and communicating with each other in ways that enhance group dynamics and help us achieve our goals? How can I further develop as a person to become more effective?” By now, the group has matured, becoming more competent, autonomous, and insightful. Group leaders can finally move into coaching roles and help members grow in skill and leadership.

Adjourning

Just as groups form, so do they end. For example, many groups or teams formed in a business context are project oriented and therefore are temporary in nature. Alternatively, a working group may dissolve due to an organizational restructuring. Just as when we graduate from school or leave home for the first time, these endings can be bittersweet, with group members feeling a combination of victory, grief, and insecurity about what is coming next. For those who like routine and bond closely with fellow group members, this transition can be particularly challenging. Group leaders and members alike should be sensitive to handling these endings respectfully and compassionately. An ideal way to close a group is to set aside time to debrief (“How did it all go? What did we learn?”), acknowledge each other, and celebrate a job well done.

The Punctuated-Equilibrium Model

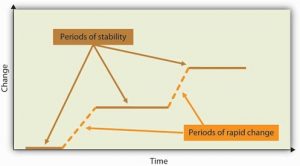

As you may have noted, the five-stage model we have just reviewed is a linear process. According to the model, a group progresses to the performing stage, at which point it finds itself in an ongoing, smooth- sailing situation until the group dissolves. In reality, subsequent researchers, most notably Joy H. Karriker, have found that the life of a group is much more dynamic and cyclical in nature (Karriker, 2005). For example, a group may operate in the performing stage for several months. Then, because of a disruption, such as a competing emerging technology that changes the rules of the game or the introduction of a new CEO, the group may move back into the storming phase before returning to performing. Ide- ally, any regression in the linear group progression will ultimately result in a higher level of functioning. Proponents of this cyclical model draw from behavioral scientist Connie Gersick’s study of punctuated equilibrium (Gersick, 1991).

The concept of punctuated equilibrium was first proposed in 1972 by paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould, who both believed that evolution occurred in rapid, radical spurts rather than gradually over time. Identifying numerous examples of this pattern in social behavior, Gersick found that the concept applied to organizational change. She proposed that groups remain fairly static, maintaining a certain equilibrium for long periods of time. Change during these periods is incremental, largely due to the resistance to change that arises when systems take root and processes become institutionalized. In this model, revolutionary change occurs in brief, punctuated bursts, generally catalyzed by a crisis or problem that breaks through the systemic inertia and shakes up the deep organizational structures in place. At this point, the organization or group has the opportunity to learn and create new structures that are better aligned with current realities. Whether the group does this is not guaranteed. In sum, in Gersick’s model, groups can repeatedly cycle through the storming and performing stages, with revolutionary change taking place during short transitional windows. For organizations and groups who under- stand that disruption, conflict, and chaos are inevitable in the life of a social system, these disruptions represent opportunities for innovation and creativity.

Cohesion

Cohesion can be thought of as a kind of social glue. It refers to the degree of camaraderie within the group. Cohesive groups are those in which members are attached to each other and act as one unit. Generally speaking, the more cohesive a group is, the more productive it will be and the more rewarding the experience will be for the group’s members (Beal et al., 2003; Evans & Dion, 1991). Members of cohesive groups tend to have the following characteristics: They have a collective identity; they experience a moral bond and a desire to remain part of the group; they share a sense of purpose, working together on a meaningful task or cause; and they establish a structured pattern of communication.

The fundamental factors affecting group cohesion include the following:

- Similarity. The more similar group members are in terms of age, sex, education, skills, attitudes, values, and beliefs, the more likely the group will bond.

- Stability. The longer a group stays together, the more cohesive it becomes.

- Size. Smaller groups tend to have higher levels of cohesion.

- Support. When group members receive coaching and are encouraged to support their fellow team members, group identity strengthens.

- Satisfaction. Cohesion is correlated with how pleased group members are with each other’s performance, behavior, and conformity to group norms.

As you might imagine, there are many benefits in creating a cohesive group. Members are generally more personally satisfied and feel greater self-confidence and self-esteem when in a group where they feel they belong. For many, membership in such a group can be a buffer against stress, which can improve mental and physical well-being. Because members are invested in the group and its work, they are more likely to regularly attend and actively participate in the group, taking more responsibility for the group’s functioning. In addition, members can draw on the strength of the group to persevere through challenging situations that might otherwise be too hard to tackle alone.

Toolbox: Steps to Creating and Maintaining a Cohesive Team

- Align the group with the greater organization. Establish common objectives in which members can get involved.

- Let members have choices in setting their own goals. Include them in decision making at the organizational level.

- Define clear roles. Demonstrate how each person’s contribution furthers the group goal—every- one is responsible for a special piece of the puzzle.

- Situate group members in close proximity to each other. This builds familiarity.

- Give frequent praise. Both individuals and groups benefit from praise. Also encourage them to praise each other. This builds individual self-confidence, reaffirms positive behavior, and creates an overall positive atmosphere.

- Treat all members with dignity and respect. This demonstrates that there are no favorites and everyone is valued.

- Celebrate differences. This highlights each individual’s contribution while also making diversity a norm.

- Establish common rituals. Thursday morning coffee, monthly potlucks—these reaffirm group identity and create shared experiences.

Can a Group Have Too Much Cohesion?

Keep in mind that groups can have too much cohesion. Because members can come to value belonging over all else, an internal pressure to conform may arise, causing some members to modify their behavior to adhere to group norms. Members may become conflict avoidant, focusing more on trying to please each other so as not to be ostracized. In some cases, members might censor themselves to maintain the party line. As such, there is a superficial sense of harmony and less diversity of thought. Having less tolerance for deviants, who threaten the group’s static identity, cohesive groups will often excommunicate members who dare to disagree. Members attempting to make a change may even be criticized or undermined by other members, who perceive this as a threat to the status quo. The painful possibility of being marginalized can keep many members in line with the majority.

The more strongly members identify with the group, the easier it is to see outsiders as inferior, or enemies in extreme cases, which can lead to increased insularity. This form of prejudice can have a down- ward spiral effect. Not only is the group not getting corrective feedback from within its own confines, it is also closing itself off from input and a cross-fertilization of ideas from the outside. In such an environment, groups can easily adopt extreme ideas that will not be challenged. Denial increases as problems are ignored and failures are blamed on external factors. With limited, often biased, information and no 1nternal or external opposition, groups like these can make disastrous decisions. Groupthink is a group pressure phenomenon that increases the risk of the group making flawed decisions by allowing reductions in mental efficiency, reality testing, and moral judgment. Groupthink is most common in highly cohesive groups (Janis, 1972).

Cohesive groups can go awry in much milder ways. For example, group members can value their social interactions so much that they have fun together but spend little time on accomplishing their assigned task. Or a group’s goal may begin to diverge from the larger organization’s goal and those trying to uphold the organization’s goal may be ostracized (e.g., teasing the class “brain” for doing well in school).

In addition, research shows that cohesion leads to acceptance of group norms (Goodman, Ravlin, & Schminke, 1987). Groups with high task commitment do well, but imagine a group where the norms are to work as little as possible? As you might imagine, these groups get little accomplished and can actually work together against the organization’s goals.

Social Loafing

Social loafing refers to the tendency of individuals to put in less effort when working in a group context. This phenomenon, also known as the Ringelmann effect, was first noted by French agricultural engineer Max Ringelmann in 1913. In one study, he had people pull on a rope individually and in groups. He found that as the number of people pulling increased, the group’s total pulling force was less than the individual efforts had been when measured alone (Karau & Williams, 1993).

Why do people work less hard when they are working with other people? Observations show that as the size of the group grows, this effect becomes larger as well (Karau & Williams, 1993). The social loafing tendency is less a matter of being lazy and more a matter of perceiving that one will receive neither one’s fair share of rewards if the group is successful nor blame if the group fails. Rationales for this behavior include, “My own effort will have little effect on the outcome,” “Others aren’t pulling their weight, so why should I?” or “I don’t have much to contribute, but no one will notice anyway.” This is a consistent effect across a great number of group tasks and countries (Gabrenya, Latane, & Wang, 1983; Harkins & Petty, 1982; Taylor & Faust, 1952; Ziller, 1957). Research also shows that perceptions of fairness are related to less social loafing (Price, Harrison, & Gavin, 2006). Therefore, teams that are deemed as more fair should also see less social loafing.

Toolbox: Tips for Preventing Social Loafing in Your Group

When designing a group project, here are some considerations to keep in mind:

- Carefully choose the number of individuals you need to get the task done. The likelihood of social loafing increases as group size increases (especially if the group consists of 10 or more people), because it is easier for people to feel unneeded or inadequate, and it is easier for them to “hide” in a larger group.

- Clearly define each member’s tasks in front of the entire group. If you assign a task to the entire group, social loafing is more likely. For example, instead of stating, “By Monday, let’s find several articles on the topic of stress,” you can set the goal of “By Monday, each of us will be responsible for finding five articles on the topic of stress.” When individuals have specific goals, they become more accountable for their performance.

- Design and communicate to the entire group a system for evaluating each person’s contribution. You may have a midterm feedback session in which each member gives feedback to every other member. This would increase the sense of accountability individuals have. You may even want to discuss the principle of social loafing in order to discourage it.

- Build a cohesive group. When group members develop strong relational bonds, they are more committed to each other and the success of the group, and they are therefore more likely to pull their own weight.

- Assign tasks that are highly engaging and inherently rewarding. Design challenging, unique, and varied activities that will have a significant impact on the individuals themselves, the organization, or the external environment. For example, one group member may be responsible for crafting a new incentive-pay system through which employees can direct some of their bonus to their favorite nonprofits.

- Make sure individuals feel that they are needed. If the group ignores a member’s contributions because these contributions do not meet the group’s performance standards, members will feel discouraged and are unlikely to contribute in the future. Make sure that everyone feels included and needed by the group.

Collective Efficacy

Collective efficacy refers to a group’s perception of its ability to successfully perform well (Bandura, 1997). Collective efficacy is influenced by a number of factors, including watching others (“that group did it and we’re better than them”), verbal persuasion (“we can do this”), and how a person feels (“this is a good group”). Research shows that a group’s collective efficacy is related to its performance (Gully et al., 2002; Porter, 2005; Tasa, Taggar, & Seijts, 2007). In addition, this relationship is higher when task interdependence (the degree an individual’s task is linked to someone else’s work) is high rather than low.

Key Takeaway

Groups may be either formal or informal. Groups go through developmental stages much like individuals do. The forming-storming-norming-performing-adjourning model is useful in prescribing stages that groups should pay attention to as they develop. The punctuated-equilibrium model of group development argues that groups often move forward during bursts of change after long periods without change. Groups that are simi- lar, stable, small, supportive, and satisfied tend to be more cohesive than groups that are not. Cohesion can help support group performance if the group values task completion. Too much cohesion can also be a concern for groups. Social loafing increases as groups become larger. When collective efficacy is high, groups tend to perform better.

9.3 Understanding Team Design Characteristics

Effective teams give companies a significant competitive advantage. In a high-functioning team, the sum is truly greater than the parts. Team members not only benefit from each other’s diverse experiences and perspectives but also stimulate each other’s creativity. Plus, for many people, working in a team can be more fun than working alone.

Differences Between Groups and Teams

Organizations consist of groups of people. What exactly is the difference between a group and a team? A group is a collection of individuals. Within an organization, groups might consist of project-related groups such as a product group or division, or they can encompass an entire store or branch of a company. The performance of a group consists of the inputs of the group minus any process losses, such as the quality of a product, ramp-up time to production, or the sales for a given month. Process loss is any aspect of group interaction that inhibits group functioning.

Why do we say group instead of team? A collection of people is not a team, though they may learn to function in that way. A team is a cohesive coalition of people working together to achieve mutual goals. Being on a team does not equate to a total suppression of personal agendas, but it does require a commitment to the vision and involves each individual working toward accomplishing the team’s objective. Teams differ from other types of groups in that members are focused on a joint goal or product, such as a presentation, discussing a topic, writing a report, creating a new design or prototype, or winning a team Olympic medal. Moreover, teams also tend to be defined by their relatively smaller size. For example, according to one definition, “A team is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they are mutually account- able” (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993).

The purpose of assembling a team is to accomplish larger, more complex goals than what would be possible for an individual working alone or even the simple sum of several individuals’ working independently. Teamwork is also needed in cases in which multiple skills are tapped or where buy-in is required from several individuals. Teams can, but do not always, provide improved performance. Working together to further a team agenda seems to increase mutual cooperation between what are often competing factions. The aim and purpose of a team is to perform, get results, and achieve victory in the workplace. The best managers are those who can gather together a group of individuals and mold them into an effective team.

The key properties of a true team include collaborative action in which, along with a common goal, teams have collaborative tasks. Conversely, in a group, individuals are responsible only for their own area. They also share the rewards of strong team performance with their compensation based on shared outcomes. Compensation of individuals must be based primarily on a shared outcome, not individual performance. Members are also willing to sacrifice for the common good, in which individuals give up scarce resources for the common good instead of competing for those resources. For example, in soccer and basketball teams, the individuals actively help each other, forgo their own chance to score by passing the ball, and win or lose collectively as a team.

The early 1990s saw a dramatic rise in the use of teams within organizations, along with dramatic results such as the Miller Brewing Company increasing productivity 30% in the plants that used self-directed teams compared to those that used the traditional organization. This same method allowed Texas Instruments Inc. in Malaysia to reduce defects from 100 parts per million to 20 parts per million. In addition, Westinghouse Electric Corporation reduced its cycle time from 12 to 2 weeks and Harris Corporation was able to achieve an 18% reduction in costs (Welins, Byham, & Dixon, 1994). The team method has served countless companies over the years through both quantifiable improvements and more subtle individual worker-related benefits.

Companies like Schneider Electric, maker of Square D circuit breakers, switched to self-directed teams and found that overtime on machines such as the punch-press dropped 70%. Productivity increased because the set-up operators themselves were able to manipulate the work in much more effective ways than a supervisor could dictate (Moskal, 1988). In 2001, clothing retailer Chico’s Retailer Services Inc. was looking to grow its business. The company hired Scott Edmonds as president, and 2 years later revenues had almost doubled from $378 million to $760 million. By 2006, revenues were $1.6 billion and Chico’s had 9 years of double-digit same-store sales growth. What did Edmonds do to get these results? He created a horizontal organization with high-performance teams that were empowered with decision- making ability and accountability for results.

The use of teams also began to increase because advances in technology have resulted in more complex systems that require contributions from multiple people across the organization. Overall, team-based organizations have more motivation and involvement, and teams can often accomplish more than individuals (Cannon-Bowers & Salas, 2001). It is no wonder organizations are relying on teams more and more.

It is important to keep in mind that teams are not a cure-all for organizations. To determine whether a team is needed, organizations should consider whether a variety of knowledge, skills, and abilities are needed, whether ideas and feedback are needed from different groups within the organization, how inter- dependent the tasks are, if wide cooperation is needed to get things done, and whether the organization would benefit from shared goals (Rees, 1997). If the answer to these questions is yes, then a team or teams might make sense. For example, research shows that the more team members perceive that out- comes are interdependent, the better they share information and the better they perform (De Dreu, 2007). Let’s take a closer look at the different team characteristics, types of teams companies use, and how to design effective teams.

Team Tasks

Teams differ in terms of the tasks they are trying to accomplish. Richard Hackman identified three major classes of tasks: production tasks, idea-generation tasks, and problem-solving tasks (Hackman, 1976). Production tasks include actually making something, such as a building, product, or a marketing plan. Idea-generation tasks deal with creative tasks, such as brainstorming a new direction or creating a new process. Problem-solving tasks refer to coming up with plans for actions and making decisions. For example, a team may be charged with coming up with a new marketing slogan, which is an idea-generation task, while another team might be asked to manage an entire line of products, including making decisions about products to produce, managing the production of the product lines, marketing them, and staffing their division. The second team has all three types of tasks to accomplish at different points in time.

Another key to understanding how tasks are related to teams is to understand their level of task interdependence. Task interdependence refers to the degree that team members are dependent on one another to get information, support, or materials from other team members to be effective. Research shows that self-managing teams are most effective when their tasks are highly interdependent (Langfred, 2005; Liden, Wayne, & Bradway, 1997). There are three types of task interdependence. Pooled interdependence exists when team members may work independently and simply combine their efforts to create the team’s output. For example, when students meet to divide the section of a research paper and one person simply puts all the sections together to create one paper, the team is using the pooled interdependence model. However, they might decide that it makes more sense to start with one person writing the introduction of their research paper, then the second person reads what was written by the first person and, drawing from this section, writes about the findings within the paper. Using the findings section, the third person writes the conclusions. If one person’s output becomes another person’s input, the team would be experiencing sequential interdependence. And finally, if the student team decided that in order to create a top-notch research paper they should work together on each phase of the research paper so that their best ideas would be captured at each stage, they would be undertaking reciprocal interdependence. Another important type of interdependence that is not specific to the task itself is outcome interdependence, in which the rewards that an individual receives depend on the performance of others.

Team Roles

Robert Sutton points out that the success of U.S. Airways Flight 1549 to land with no fatalities when it crashed into the Hudson River in New York City is a good example of an effective work team (Sutton, 2009). For example, reports show that Captain Chesley Sullenberger took over flying from copilot Jeff Skiles, who had handled the takeoff, but had less experience in the Airbus (Caruso, 2009). This is consistent with the research findings that effective teams divide up tasks so the best people are in the best positions.

Studies show that individuals who are more aware of team roles and the behavior required for each role perform better than individuals who do not. This fact remains true for both student project teams as well as work teams, even after accounting for intelligence and personality (Mumford et al., 2008). Early research found that teams tend to have two categories of roles consisting of those related to the tasks at hand and those related to the team’s functioning. For example, teams that focus only on production at all costs may be successful in the short run, but if they pay no attention to how team members feel about working 70 hours a week, they are likely to experience high turnover.

Source: Mumford, T. V., Van Iddekinge, C., Morgeson, F. P., & Campion, M. A. (2008). The team role test: Development and validation of a team role knowledge situational judgment test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 250–267; Mumford, T. V., Campion, M. A., & Morgeson, F. P. (2006). Situational judgments in work teams: A team role typology. In J. A. Weekley and R. E. Ployhart (Eds.), Situational judgment tests: Theory, measurement, and application (pp. 319–344). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

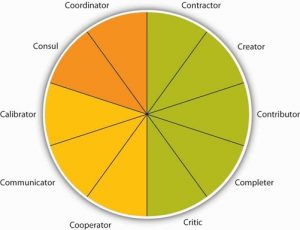

Based on decades of research on teams, 10 key roles have been identified (Bales, 1950; Benne & Sheats, 1948; Belbin, 1993). Team leadership is effective when leaders are able to adapt the roles they are con- tributing or asking others to contribute to fit what the team needs given its stage and the tasks at hand (Kozlowski et al., 1996; Kozlowski et al., 1996). Ineffective leaders might always engage in the same task role behaviors, when what they really need is to focus on social roles, put disagreements aside, and get back to work. While these behaviors can be effective from time to time, if the team doesn’t modify its role behaviors as things change, they most likely will not be effective.

Task Roles

Five roles make up the task portion of the typology. The contractor role includes behaviors that serve to organize the team’s work, including creating team timelines, production schedules, and task sequencing. The creator role deals more with changes in the team’s task process structure. For example, reframing the team goals and looking at the context of goals would fall under this role. The contributor role is important, because it brings information and expertise to the team. This role is characterized by sharing knowledge and training with those who have less expertise to strengthen the team. Research shows that teams with highly intelligent members and evenly distributed workloads are more effective than those with uneven workloads (Ellis et al., 2003). The completer role is also important, as it transforms ideas into action. Behaviors associated with this role include following up on tasks, such as gathering needed background information or summarizing the team’s ideas into reports. Finally, the critic role includes “devil’s advocate” behaviors that go against the assumptions being made by the team.

Social Roles

Social roles serve to keep the team operating effectively. When the social roles are filled, team members feel more cohesive, and the group is less prone to suffer process losses or biases such as social loafing, groupthink, or a lack of participation from all members. Three roles fall under the umbrella of social roles. The cooperator role includes supporting those with expertise toward the team’s goals. This is a proactive role. The communicator role includes behaviors that are targeted at collaboration, such as practicing good listening skills and appropriately using humor to diffuse tense situations. Having a good communicator helps the team to feel more open to sharing ideas. The calibrator role is an important one that serves to keep the team on track in terms of suggesting any needed changes to the team’s process. This role includes initiating discussions about potential team problems such as power struggles or other tensions. Similarly, this role may involve settling disagreements or pointing out what is working and what is not in terms of team process.

Boundary-Spanning Roles

The final two goals are related to activities outside the team that help to connect the team to the larger organization (Anacona, 1990; Anacona, 1992; Druskat & Wheeler, 2003). Teams that engage in a greater level of boundary-spanning behaviors increase their team effectiveness (Marrone, Tesluk, & Carson, 2007). The consul role includes gathering information from the larger organization and informing those within the organization about team activities, goals, and successes. Often the consul role is filled by team managers or leaders. The coordinator role includes interfacing with others within the organization so that the team’s efforts are in line with other individuals and teams within the organization.

Types of Teams

There are several types of temporary teams. In fact, one-third of all teams in the United States are temporary in nature (Gordon, 1992). An example of a temporary team is a task force that is asked to address a specific issue or problem until it is resolved. Other teams may be temporary or ongoing, such as product development teams. In addition, matrix organizations have cross-functional teams in which individuals from different parts of the organization staff the team, which may be temporary or long-standing in nature.

Virtual teams are teams in which members are not located in the same physical place. They may be in different cities, states, or even different countries. Some virtual teams are formed by necessity, such as to take advantage of lower labor costs in different countries with upwards of 8.4 million individuals working virtually in at least one team (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). Often, virtual teams are formed to take advantage of distributed expertise or time—the needed experts may be living in different cities. A company that sells products around the world, for example, may need technologists who can solve customer problems at any hour of the day or night. It may be difficult to find the caliber of people needed who would be willing to work at 2:00 a.m. on a Saturday, for example. So companies organize virtual technical support teams. BakBone Software Inc., for example, has a 13-member technical support team. All members have degrees in computer science and are divided among offices in California, Maryland, England, and Tokyo. BakBone believes it has been able to hire stronger candidates by drawing from a diverse talent pool and hiring in different geographic regions rather than being limited to one region or time zone (Alexander, 2000).

Despite potential benefits, virtual teams present special management challenges. Managers often think that they have to see team members working in order to believe that work is being done. Because this kind of oversight is impossible in virtual team situations, it is important to devise evaluation schemes that focus on deliverables. Are team members delivering what they said they would? In self-managed teams, are team members producing the results the team decided to measure itself on?

Another special challenge of virtual teams is building trust. Will team members deliver results just as they would in face-to-face teams? Can members trust each other to do what they said they would do? Companies often invest in bringing a virtual team together at least once so members can get to know each other and build trust (Kirkman et al., 2002). In manager-led virtual teams, managers should be held accountable for their team’s results and evaluated on their ability as a team leader.

Finally, communication is especially important in virtual teams, be it through e-mail, phone calls, conference calls, or project management tools that help organize work. If individuals in a virtual team are not fully engaged and tend to avoid conflict, team performance can suffer (Montoya-Weiss, Massey, & Song, 2001). A wiki is an Internet-based method for many people to collaborate and contribute to a document or discussion. Essentially, the document remains available for team members to access and amend at any time. The most famous example is Wikipedia, which is gaining traction as a way to structure project work globally and get information into the hands of those that need it. Empowered organizations put information into everyone’s hands (Kirkman & Rosen, 2000). Research shows that empowered teams are more effective than those that are not empowered (Mathieu, Gilson, & Ruddy, 2006).

Top management teams are appointed by the chief executive officer (CEO) and, ideally, reflect the skills and areas that the CEO considers vital for the company. There are no formal rules about top management team design or structure. The top team often includes representatives from functional areas, such as finance, human resources, and marketing, or key geographic areas, such as Europe, Asia, and North America. Depending on the company, other areas may be represented, such as legal counsel or the company’s chief technologist. Typical top management team member titles include chief operating officer (COO), chief financial officer (CFO), chief marketing officer (CMO), or chief technology officer (CTO). Because CEOs spend an increasing amount of time outside their companies (e.g., with suppliers, customers, and regulators), the role of the COO has taken on a much higher level of internal operating responsibilities. In most American companies, the CEO also serves as chairman of the board and can have the additional title of president. Companies have top teams to help set the company’s vision and strategic direction. Top teams make decisions on new markets, expansions, acquisitions, or divestitures. The top team is also important for its symbolic role: How the top team behaves dictates the organization’s culture and priorities by allocating resources and by modeling behaviors that will likely be emulated lower down in the organization. Importantly, the top team is most effective when team composition is diverse—functionally and demographically—and when it can truly operate as a team, not just as a group of individual executives (Carpenter, Geletkanycz, & Sanders, 2004).

In a study of 15 firms that demonstrated excellence, defined as sustained performance over a 15-year period, leadership researcher Jim Collins noted that those firms attended to people first and strategy second. “They got the right people on the bus, moved the wrong people off the bus, ushered the right people to the right seats—then they figured out where to drive it” (Collins, 2001). The best teams plan for turnover. Succession planning is the process of identifying future members of the top management team. Effective succession planning allows the best top teams to achieve high performance today and create a legacy of high performance for the future.

Team Leadership and Autonomy

Teams also vary in terms of how they are led. Traditional manager-led teams are teams in which the manager serves as the team leader. The manager assigns work to other team members. These types of teams are the most natural to form, with managers having the power to hire and fire team members and being held accountable for the team’s results.

Self-managed teams are a new form of team that rose in popularity with the Total Quality Movement in the 1980s. Unlike manager-led teams, these teams manage themselves and do not report directly to a supervisor. Instead, team members select their own leader, and they may even take turns in the leader- ship role. Self-managed teams also have the power to select new team members. As a whole, the team shares responsibility for a significant task, such as assembly of an entire car. The task is ongoing rather than a temporary task such as a charity fund drive for a given year.

Organizations began to use self-managed teams as a way to reduce hierarchy by allowing team members to complete tasks and solve problems on their own. The benefits of self-managed teams extend much further. Research has shown that employees in self-managed teams have higher job satisfaction, increased self-esteem, and grow more on the job. The benefits to the organization include increased productivity, increased flexibility, and lower turnover. Self-managed teams can be found at all levels of the organization, and they bring particular benefits to lower level employees by giving them a sense of ownership of their jobs that they may not otherwise have. The increased satisfaction can also reduce absenteeism, because employees do not want to let their team members down.

Typical team goals are improving quality, reducing costs, and meeting deadlines. Teams also have a “stretch” goal—a goal that is difficult to reach but important to the business unit. Many teams also have special project goals. Texas Instruments (TI), a company that makes semiconductors, used self-directed teams to make improvements in work processes (Welins, Byham, & Dixon, 1994). Teams were allowed to set their own goals in conjunction with managers and other teams. TI also added an individual com- ponent to the typical team compensation system. This individual component rewarded team members for learning new skills that added to their knowledge. These “knowledge blocks” include topics such as leadership, administration, and problem solving. The team decides what additional skills people might need to help the team meet its objectives. Team members would then take classes and/or otherwise demonstrate their proficiency in that new skill on the job in order to get certification for mastery of the skill. Individuals could then be evaluated based on their contribution to the team and how they are building skills to support the team.

Self-managed teams are empowered teams, which means that they have the responsibility as well as the authority to achieve their goals. Team members have the power to control tasks and processes and to make decisions. Research shows that self-managed teams may be at a higher risk of suffering from negative outcomes due to conflict, so it is important that they are supported with training to help them deal with conflict effectively (Alper, Tjosvold, & Law, 2000; Langfred, 2007). Self-managed teams may still have a leader who helps them coordinate with the larger organization (Morgeson, 2005). For a product team composed of engineering, production, and marketing employees, being empowered means that the team can decide everything about a product’s appearance, production, and cost without having to get permission or sign-off from higher management. As a result, empowered teams can more effectively meet tighter deadlines. At AT&T Inc., for example, the model-4200 phone team cut development time in half while lowering costs and improving quality by using the empowered team approach (Parker, 1994). A special form of self-managed teams are self-directed teams, which also determine who will lead them with no external oversight.

Traditionally managed teams |

Self-managed teams |

Self-directed team |

| • Leader resides outside the team

• Potential for low autonomy |

• The team manages itself but still has a team leader

• Potential for low, medium, or high autonomy |

• The team makes all decisions internally about leadership and how work is done

• Potential for high autonomy |

Team leadership is a major determinant of how autonomous a team can be.

Designing Effective Teams

Designing an effective team means making decisions about team composition (who should be on the team), team size (the optimal number of people on the team), and team diversity (should team members be of similar background, such as all engineers, or of different backgrounds). Answering these questions will depend, to a large extent, on the type of task that the team will be performing. Teams can be charged with a variety of tasks, from problem solving to generating creative and innovative ideas to managing the daily operations of a manufacturing plant.

Who Are the Best Individuals for the Team?

A key consideration when forming a team is to ensure that all the team members are qualified for the roles they will fill for the team. This process often entails understanding the knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) of team members as well as the personality traits needed before starting the selection process (Humphrey et al., 2007). When talking to potential team members, be sure to communicate the job requirements and norms of the team. To the degree that this is not possible, such as when already existing groups are utilized, think of ways to train the team members as much as possible to help ensure success. In addition to task knowledge, research has shown that individuals who understand the concepts covered in this chapter and in this book, such as conflict resolution, motivation, planning, and leader- ship, actually perform better on their jobs. This finding holds for a variety of jobs, including being an officer in the U.S. Air Force, an employee at a pulp mill, or a team member at a box manufacturing plant (Hirschfeld et al., 2006; Stevens & Campion, 1999).

How Large Should My Team Be?

Interestingly, research has shown that regardless of team size, the most active team member speaks 43% of the time. The difference is that the team member who participates the least in a 3-person team is still active 23% of the time versus only 3% in a 10-person team (McGrath, 1984; Solomon, 1960). When deciding team size, a good rule of thumb is a size of two to 20 members. Research shows that groups with more than 20 members have less cooperation (Gratton & Erickson, 2007). The majority of teams have 10 members or less, because the larger the team, the harder it is to coordinate and interact as a team. With fewer individuals, team members are more able to work through differences and agree on a common plan of action. They have a clearer understanding of others’ roles and greater accountability to fulfill their roles (remember social loafing?). Some tasks, however, require larger team sizes because of the need for diverse skills or because of the complexity of the task. In those cases, the best solution is to create subteams in which one member from each subteam is a member of a larger coordinating team. The relationship between team size and performance seems to greatly depend on the level of task inter- dependence, with some studies finding larger teams outproducing smaller teams and other studies finding just the opposite (Campion, Medsker, & Higgs, 1993; Magjuka & Baldwin, 1991; Vinokur-Kaplan, 1995). The bottom line is that team size should be matched to the goals of the team.

How Diverse Should My Team Be?

Team composition and team diversity often go hand in hand. Teams whose members have complementary skills are often more successful, because members can see each other’s blind spots. One team member’s strengths can compensate for another’s weaknesses (Jackson, Joshi, & Erhardt, 2003; van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, 2004). For example, consider the challenge that companies face when trying to forecast future sales of a given product. Workers who are educated as forecasters have the ana- lytic skills needed for forecasting, but these workers often lack critical information about customers. Salespeople, in contrast, regularly communicate with customers, which means they’re in the know about upcoming customer decisions. But salespeople often lack the analytic skills, discipline, or desire to enter this knowledge into spreadsheets and software that will help a company forecast future sales. Putting forecasters and salespeople together on a team tasked with determining the most accurate product fore- cast each quarter makes the best use of each member’s skills and expertise.

Diversity in team composition can help teams come up with more creative and effective solutions. Research shows that teams that believe in the value of diversity performed better than teams that do not (Homan et al., 2007). The more diverse a team is in terms of expertise, gender, age, and background, the more ability the group has to avoid the problems of groupthink (Surowiecki, 2005). For example, different educational levels for team members were related to more creativity in R&D teams and faster time to market for new products (Eisenhardt & Tabrizi, 1995; Shin & Zhou, 2007).

Members will be more inclined to make different kinds of mistakes, which means that they’ll be able to catch and correct those mistakes.

Key Takeaway

Groups and teams are not the same thing. Organizations have moved toward the extensive use of teams within organizations. The tasks a team is charged with accomplishing affect how they perform. In general, task interdependence works well for self-managing teams. Team roles consist of task, social, and boundary- spanning roles. Different types of teams include task forces, product development teams, cross-functional teams, and top management teams. Team leadership and autonomy varies, depending on whether the team is traditionally managed, self-managed, or self-directed. Teams are most effective when they comprise members with the right skills for the tasks at hand, are not too large, and contain diversity across team members.

9.4 Management of Teams

Establishing Team Norms

Norms are shared expectations about how things operate within a group or team. Just as new employees learn to understand and share the assumptions, norms, and values that are part of an organization’s culture, they also must learn the norms of their immediate team. This understanding helps teams be more cohesive and perform better. Norms are a powerful way of ensuring coordination within a team. For example, is it acceptable to be late to meetings? How prepared are you supposed to be at the meetings? Is it acceptable to criticize someone else’s work? These norms are shaped early during the life of a team and affect whether the team is productive, cohesive, and successful.

Team Contracts

Scientific research, as well as experience working with thousands of teams, show that teams that are able to articulate and agree on established ground rules, goals, and roles and develop a team contract around these standards are better equipped to face challenges that may arise within the team (Katzenback & Smith, 1993; Porter & Lilly, 1996). Having a team contract does not necessarily mean that the team will be successful, but it can serve as a road map when the team veers off course. The following questions can help to create a meaningful team contract:

- Team Values and Goals

- What are our shared team values?

- What is our team goal?

- Team Roles and Leadership

- Who does what within this team? (Who takes notes at the meeting? Who sets the agenda? Who assigns tasks? Who runs the meetings?)

- Does the team have a formal leader?

- If so, what are his or her roles?

- Team Decision Making

- How are minor decisions made?

- How are major decisions made?

- Team Communication

- Who do you contact if you cannot make a meeting?

- Who communicates with whom?

- How often will the team meet?

- Team Performance

- What constitutes good team performance?

- What if a team member tries hard but does not seem to be producing quality work?

- How will poor attendance/work quality be dealt with?

Team Meetings

Anyone who has been involved in a team knows it involves team meetings. While few individuals relish the idea of team meetings, they serve an important function in terms of information sharing and decision making. They also serve an important social function and can help to build team cohesion and a task function in terms of coordination. Unfortunately, we’ve all attended meetings that were a waste of time and little happened that couldn’t have been accomplished by reading an e-mail in 5 minutes. To run effective meetings, it helps to think of meetings in terms of three sequential steps (Haynes, 1997).

Before the Meeting

Much of the effectiveness of a meeting is determined before the team gathers. There are three key things you can do to ensure the team members get the most out of their meeting.

Is a meeting needed? Leaders should do a number of things prior to the meeting to help make it effective. The first thing is to be sure a meeting is even needed. If the meeting is primarily informational in nature, ask yourself if it is imperative that the group fully understands the information and if future decisions will be built upon this information. If so, a meeting may be needed. If not, perhaps simply communicating with everyone in a written format will save valuable time. Similarly, decision-making meetings make the most sense when the problem is complex and important, there are questions of fairness to be resolved, and commitment is needed moving forward.

Create and distribute an agenda. An agenda is important in helping to inform those invited about the purpose of the meeting. It also helps organize the flow of the meeting and keep the team on track.

Send a reminder prior to the meeting. Reminding everyone of the purpose, time, and location of the meeting helps everyone prepare themselves. Anyone who has attended a team meeting only to find there is no reason to meet because members haven’t completed their agreed-upon tasks knows that, as a result, team performance or morale can be negatively impacted. Follow up to make sure everyone is prepared. As a team member, inform others immediately if you will not be ready with your tasks so that they can determine whether the meeting should be postponed.

During the Meeting

During the meeting there are several things you can do to make sure the team starts and keeps on track.

Start the meeting on time. Waiting for members who are running late only punishes those who are on time and reinforces the idea that it’s OK to be late. Starting the meeting promptly sends an important signal that you are respectful of everyone’s time.

Follow the meeting agenda. Veering off agenda communicates to members that the agenda is not important. It also makes it difficult for others to keep track of where you are in the meeting.

Manage group dynamics for full participation. As you’ve seen in this chapter, a number of group dynamics can limit a team’s functioning. Be on the lookout for full participation and engagement from all team members, as well as any potential problems such as social loafing, group conflict, or groupthink.

Summarize the meeting with action items. Be sure to clarify team member roles moving forward. If individuals’ tasks are not clear, chances are that role confusion will arise later. There should be clear notes from the meeting regarding who is responsible for each action item and the time frames associated with next steps.

End the meeting on time. This is vitality important, as it shows that you respect everyone’s time and are organized. If another meeting is needed to follow up, schedule it later, but don’t let the meeting run over.

After the Meeting

Follow up on action items. During the meeting, participants probably generated several action items. It is likely that you’ll need to follow up on the action items of others.

Key Takeaway

Much like group development, team socialization takes place over the life of the team. The stages move from evaluation to commitment to role transition. Team norms are important for the team process and help to establish who is doing what for the team and how the team will function. Creating a team contract helps with this process. Keys to address in a team contract are team values and goals, team roles and leadership, team decision making, team communication expectations, and how team performance is characterized. Team meetings can help a team coordinate and share information. Effective meetings include preparation, management during the meeting, and follow-up on action items generated in the meeting.

9.5 Barriers to Effective Teams

Problems can arise in any team that will hurt the team’s effectiveness. Here are some common problems faced by teams and how to deal with them.

Common Problems Faced by Teams Challenges of Knowing where to Begin

At the start of a project, team members may be at a loss as to how to begin. Also, they may have reached the end of a task but are unable to move on to the next step or put the task to rest. Floundering often results from a lack of clear goals, so the remedy is to go back to the team’s mission or plan and make sure that it is clear to everyone. Team leaders can help move the team past floundering by asking, “What is holding us up? Do we need more data? Do we need assurances or support? Does anyone feel that we’ve missed something important?”

Dominating Team Members

Some team members may have a dominating personality that encroaches on the participation or air time of others. This overbearing behavior may hurt the team morale or the momentum of the team. A good way to overcome this barrier is to design a team evaluation to include a “balance of participation” in meetings. Knowing that fair and equitable participation by all will affect the team’s performance evaluation will help team members limit domination by one member and encourage participation from all members, even shy or reluctant ones. Team members can say, “We’ve heard from Mary on this issue, so let’s hear from others about their ideas.”

Poor Performance of Team Members

Research shows that teams deal with poor performers in different ways, depending on members’ perceptions of the reasons for poor performance (Jackson & LePine, 2003). In situations in which the poor performer is perceived as lacking in ability, teams are more likely to train the member. When members perceive the individual as simply being low on motivation, they are more likely to try to motivate or reject the poor performer. Keep in mind that justice is an important part of keeping individuals working hard for the team (Colquitt, 2004). Be sure that poor performers are dealt with in a way that is deemed fair by all the team members.

Poorly Managed Team Conflict

Disagreements among team members are normal and should be expected. Healthy teams raise issues and discuss differing points of view, because that will ultimately help the team reach stronger, more well-reasoned decisions. Unfortunately, sometimes disagreements arise owing to personality issues or feuds that predated a team’s formation. Ideally, teams should be designed to avoid bringing adversaries together on the same team. If that is not possible, the next best solution is to have adversaries discuss their issues privately, so the team’s progress is not disrupted. The team leader or other team member can offer to facilitate the discussion. One way to make a discussion between conflicting parties meaningful is to form a behavioral contract between the two parties. That is, if one party agrees to do X, then the other will agree to do Y (Scholtes, 1988).

Key Takeaway

Barriers to effective teams include the challenges of knowing where to begin, dominating team members, the poor performance of team members, and poorly managed team conflict.

9.6 The Role of Ethics and National Culture

Ethics and Teams

The use of teams, especially self-managing teams, has been seen as a way to overcome the negatives of bureaucracy and hierarchical control. Giving teams the authority and responsibility to make their own decisions seems to empower individuals and the team alike by distributing power more equitably. Interestingly, research by James Barker shows that sometimes replacing a hierarchy with self-managing teams can actually increase control over individual workers and constrain members more powerfully than a hierarchical system (Barker, 1993). Studying a small manufacturing company that switched to self-managing teams, Barker interviewed team members and found an unexpected result: Team members felt more closely watched under self-managing teams than under the old system. Ronald, a technical worker, said, “I don’t have to sit there and look for the boss to be around; and if the boss is not around, I can sit there and talk to my neighbor or do what I want. Now the whole team is around me and the whole team is observing what I’m doing.” Ronald said that while his old supervisor might tolerate someone coming in a few minutes late, his team had adopted a “no tolerance” policy on tardiness, and members carefully monitored their own behaviors.

Team pressure can harm a company as well. Consider a sales team whose motto of “sales above all” hurts the ability of the company to gain loyal customers (DiModica, 2008). The sales team feels pressure to lie to customers to make sales. Their misrepresentations and unethical behavior gets them the quick sale but curtails their ability to get future sales from repeat customers.

Teams Around the Globe

People from different cultures often have different beliefs, norms, and ways of viewing the world. These kinds of country-by-country differences have been studied by the GLOBE Project, in which 170 researchers collected and analyzed data on cultural values, practices, and leadership attributes from over 17,000 managers in 62 societal cultures (Javidan et al., 2006). GLOBE identified nine dimensions of culture. One of the identified dimensions is a measure called collectivism. Collectivism focuses on the degree to which the society reinforces collective over individual achievement. Collectivist societies value interpersonal relationships over individual achievement. Societies that rank high on collectivism show more close ties between individuals. The United States and Australia rank low on the collectivism dimension, whereas countries such as Mexico and Taiwan rank high on that dimension. High collectivism manifests itself in close, long-term commitment to the member group. In a collectivist culture, loyalty is paramount and overrides most other societal rules and regulations. The society fosters strong relationships in which everyone takes responsibility for fellow members of their group.

Harrison, McKinnon, Wu, and Chow explored the cultural factors that may influence how well employees adapt to fluid work groups (Harrison et al., 2000). The researchers studied groups in Taiwan and Australia. Taiwan ranks high on collectivism, while Australia ranks low. The results: Australian man- agers reported that employees adapted more readily to working in different teams, working under different leaders, and taking on leadership of project teams than the middle managers in Taiwan reported. The two samples were matched in terms of the functional background of the managers, size and industries of the firms, and local firms. These additional controls provided greater confidence in attributing the observed differences to cultural values.

In other research, researchers analyzed the evaluation of team member behavior by part-time MBA students in the United States and Mexico (Gomez, Kirkman, & Shapiro, 2000). The United States ranks low on collectivism while Mexico ranks high. They found that collectivism (measured at the individual level) had a positive relationship to the evaluation of a teammate. Furthermore, the evaluation was higher for in-group members among the Mexican respondents than among the U.S. respondents.

Power distance is another culture dimension. People in high power distance countries expect unequal power distribution and greater stratification, whether that stratification is economic, social, or political. An individual in a position of authority in these countries expects (and receives) obedience. Decision making is hierarchical, with limited participation and communication. Countries with a low power distance rating, such as Australia, value cooperative interaction across power levels. Individuals stress equality and opportunity for everyone.

Another study by researchers compared national differences in teamwork metaphors used by employees in six multinational corporations in four countries: the United States, France, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines (Gibson & Zellmer-Bruhn, 2001). They identified five metaphors: military, family, sports, associates, and community. Results showed national variation in the use of the five metaphors. Specifically, countries high in individualism (United States and France) tended to use the sports or associates metaphors, while countries high in power distance (Philippines and Puerto Rico) tended to use the military or family metaphors. Further, power distance and collectivistic values were negatively associated with the use of teamwork metaphors that emphasized clear roles and broad scope. These results suggest that the meaning of teamwork may differ across cultures and, in turn, imply potential differences in team norms and team-member behaviors.

Key Takeaway

Self-managing teams shift the role of control from management to the team itself. This can be highly effective, but if team members put too much pressure on one another, problems can arise. It is also make sure teams work toward organizational goals as well as specific team-level goals. Teams around the globe vary in terms of collectivism and power distance. These differences can affect how teams operate in countries around the world.

9.7 Green Teams at Work: The Case of New Seasons Market

Teamwork is important at New Seasons Market Inc. (a privately held company). This is a relatively small chain of upscale grocery stores in the Pacific Northwest that are built on the ideas of local identity, quality products, and employee freedom to meet the needs of customers. Formed in 1999 by a group of people with similar goals, New Seasons Market operates nine grocery stores in various Portland area neighborhoods.

Though the look and products of the stores are consistent, each store is predominantly staffed by individuals that live in the local neighborhood, enabling each store to know the needs of its customers and create an internal identity all its own.

One of the ways each store creates that identity is through Green Teams. These teams are typically composed of up to 13 paid employees from various departments. Teams join together to address social and environmental issues of sustainability within each store and its surrounding community. The idea for Green Teams originated from a group of employees in one store that assembled to tackle “green” issues in their store. Corporate managers (who also have their own Green Team) agreed that it was such a good idea that now every store is required to have a Green Team. Each team meets monthly and reports to the company sustainability coordinator. Team leadership structures vary from store to store, with some Green Teams having a single chairperson who serves the team for more than 1 year, while other teams regularly rotate leaders or even elect two cochairs to lead the cause. Teams act as liaisons between their department and the Green Team, help educate staff, and make recommendations to management. Store Green Teams also initiate community service pro- jects and help maintain the waste diversion program.

Through this flexibility, each Green Team has accomplished a variety of projects in their store and local com- munity, including wilderness and wetland cleanup, painting and weeding at a local elementary school, and helping plant gardens for low-income families. One suburban store even developed an intricate car pool pro- gram for employees to encourage a reduction in drive-alone car trips. As long as the Green Team’s focus is on their local store and community, they are granted freedom and support from corporate management. Safety and Sustainability Manager Heather Schmidt explains, “If there were too many rules, it could hold back creativity and passion. Having a balance is the key.”

Participation in Green Team initiatives has developed a friendly competition between stores and rewards employees who participate with incentives. For example, every time an employee joins in the staff car pool, his or her name is entered into a monthly drawing for a gift card. These values of support and encouragement are consistent throughout New Seasons company culture, where employees are valued for their personal contributions. As their Web site explains, “To be a truly great company means that we continually evolve to meet the changing needs of our customers, our staff and the world around us.” With these values, New Seasons Market has created “a workplace that truly believes that taking good care of our co-workers, our customers and our environment is what drives the success of our business.”

Based on information from Schmidt, H. (2010, March 12). Personal communication; Information retrieved March 20, 2010, from New Seasons Market Web site: http://www.newseasonsmarket.com; Private company information: New Seasons Market Inc. (2010). BusinessWeek. Retrieved April 3, 2010, from http://invest- ing.businessweek.com/research/stocks/private/snapshot.asp?privcapId=12004234.

9.8 Conclusion

Research shows that group formation is a beneficial but highly dynamic process. The life cycle of teams can often closely resemble various stages in individual development. In order to maintain group effectiveness, individuals should be aware of key stages as well as methods to avoid becoming stuck along the way. Good leadership skills combined with knowledge of group development will help any group perform at its peak level. Teams, though similar, are different from groups in both scope and composition. Groups are often small collections of individuals with various skill sets that combine to address a specific issue, whereas teams can be much larger and often consist of people with overlapping abilities working toward a common goal.

Many issues that can plague groups can also hinder the efficacy of a team. Problems such as social loafing or groupthink can be avoided by paying careful attention to team member differences and providing clear definitions for roles, expectancy, measurement, and rewards. Because many tasks in today’s world have become so complex, groups and teams have become an essential component of an organization’s success. The success of the team/group rests within the successful management of its members and making sure all aspects of work are fair for each member.

Adapted from: Chapter 9 of Organizational Behavior

[Author removed at request of original publisher]