Task B. Effects of Weather on Performance

| Task B. Effects of Weather on Performance | |

| References | AC 107-2; AIM; FAA-H-8083-25; FAA-G-8082-22 |

| Objective | To determine that the applicant is knowledgeable of the effects of weather on performance. |

| Knowledge | The applicant demonstrates understanding of: |

| UA.III.B.K1 | Weather factors and their effects on performance. |

| UA.III.B.K1a | a. Density altitude |

| UA.III.B.K1b | b. Wind and currents |

| UA.III.B.K1c | c. Atmospheric stability, pressure, and temperature |

| UA.III.B.K1d | d. Air masses and fronts |

| UA.III.B.K1e | e. Thunderstorms and microbursts |

| UA.III.B.K1f | f. Tornadoes |

| UA.III.B.K1g | g. Icing |

| UA.III.B.K1h | h. Hail |

| UA.III.B.K1i | i. Fog |

| UA.III.B.K1j | j. Ceiling and visibility |

| UA.III.B.K1k | k. Lightning |

| Risk Management | [Reserved] |

| Skills | [Not Applicable] |

UA.III.B.K1 Weather factors and their effects on performance (FAA-G-8082-22 pg. 21).

This chapter discusses the factors that affect aircraft performance, which include the aircraft weight, atmospheric conditions, runway environment, and the fundamental physical laws governing the forces acting on an aircraft.

Since the characteristics of the atmosphere have a major effect on performance, it is necessary to review two dominant factors—pressure and temperature.

UA.III.B.K1a Density altitude

SDP is a theoretical pressure altitude, but aircraft operate in a nonstandard atmosphere and the term density altitude is used for correlating aerodynamic performance in the nonstandard atmosphere. Density altitude is the vertical distance above sea level in the standard atmosphere at which a given density is to be found. The density of air has significant effects on the aircraft’s performance because as air becomes less dense, it reduces:

• Power because the engine takes in less air

• Thrust because a propeller is less efficient in thin air

• Lift because the thin air exerts less force on the airfoils

Density altitude is pressure altitude corrected for nonstandard temperature. As the density of the air increases (lower density altitude), aircraft performance increases; conversely as air density decreases (higher density altitude), aircraft performance decreases. A decrease in air density means a high density altitude; an increase in air density means a lower density altitude. Density altitude is used in calculating aircraft performance because under standard atmospheric conditions, air at each level in the atmosphere not only has a specific density, its pressure altitude and density altitude identify the same level.

The computation of density altitude involves consideration of pressure (pressure altitude) and temperature. Since aircraft performance data at any level is based upon air density under standard day conditions, such performance data apply to air density levels that may not be identical with altimeter indications. Under conditions higher or lower than standard, these levels cannot be determined directly from the altimeter.

Density altitude is determined by first finding pressure altitude, and then correcting this altitude for nonstandard temperature variations. Since density varies directly with pressure and inversely with temperature, a given pressure altitude may exist for a wide range of temperatures by allowing the density to vary. However, a known density occurs for any one temperature and pressure altitude. The density of the air has a pronounced effect on aircraft and engine performance. Regardless of the actual altitude of the aircraft, it will perform as though it were operating at an altitude equal to the existing density altitude.

Air density is affected by changes in altitude, temperature, and humidity. High density altitude refers to thin air, while low density altitude refers to dense air. The conditions that result in a high density altitude are high elevations, low atmospheric pressures, high temperatures, high humidity, or some combination of these factors. Lower elevations, high atmospheric pressure, low temperatures, and low humidity are more indicative of low density altitude.

Effect of Pressure on Density

Since air is a gas, it can be compressed or expanded. When air is compressed, a greater amount of air can occupy a given volume. Conversely, when pressure on a given volume of air is decreased, the air expands and occupies a greater space. At a lower pressure, the original column of air contains a smaller mass of air. The density is decreased because density is directly proportional to pressure. If the pressure is doubled, the density is doubled; if the pressure is lowered, the density is lowered. This statement is true only at a constant temperature.

Effect of Temperature on Density

Increasing the temperature of a substance decreases its density. Conversely, decreasing the temperature increases the density. Thus, the density of air varies inversely with temperature. This statement is true only at a constant pressure.

In the atmosphere, both temperature and pressure decrease with altitude and have conflicting effects upon density. However, a fairly rapid drop in pressure as altitude increases usually has a dominating effect. Hence, pilots can expect the density to decrease with altitude.

Effect of Humidity (Moisture) on Density

The preceding paragraphs refer to air that is perfectly dry. In reality, it is never completely dry. The small amount of water vapor suspended in the atmosphere may be almost negligible under certain conditions, but in other conditions humidity may become an important factor in the performance of an aircraft. Water vapor is lighter than air; consequently, moist air is lighter than dry air. Therefore, as the water content of the air increases, the air becomes less dense, increasing density altitude and decreasing performance. It is lightest or least dense when, in a given set of conditions, it contains the maximum amount of water vapor.

Humidity, also called relative humidity, refers to the amount of water vapor contained in the atmosphere and is expressed as a percentage of the maximum amount of water vapor the air can hold. This amount varies with temperature. Warm air holds more water vapor, while cold air holds less. Perfectly dry air that contains no water vapor has a relative humidity of zero percent, while saturated air, which cannot hold any more water vapor, has a relative humidity of 100 percent. Humidity alone is usually not considered an important factor in calculating density altitude and aircraft performance, but it is a contributing factor.

As temperature increases, the air can hold greater amounts of water vapor. When comparing two separate air masses, the first warm and moist (both qualities tending to lighten the air) and the second cold and dry (both qualities making it heavier), the first must be less dense than the second. Pressure, temperature, and humidity have a great influence on aircraft performance because of their effect upon density. There are no rules of thumb that can be easily applied, but the affect of humidity can be determined using several online formulas. In the first example, the pressure is needed at the altitude for which density altitude is being sought. Using Figure 4-2, select the barometric pressure closest to the associated altitude. As an example, the pressure at 8,000 feet is 22.22 “Hg. Using the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) website (www.srh.noaa.gov/ epz/?n=wxcalc_densityaltitude) for density altitude, enter the 22.22 for 8,000 feet in the station pressure window. Enter a temperature of 80° and a dew point of 75°. The result is a density altitude of 11,564 feet. With no humidity, the density altitude would be almost 500 feet lower.

Another website (www.wahiduddin.net/calc/density_ altitude.htm) provides a more straight forward method of determining the effects of humidity on density altitude without using additional interpretive charts. In any case, the effects of humidity on density altitude include a decrease in overall performance in high humidity conditions.

UA.III.B.K1b Wind and currents (FAA-H-8083-25 Pg. 12-7).

Air flows from areas of high pressure into areas of low pressure because air always seeks out lower pressure. The combination of atmospheric pressure differences, Coriolis force, friction, and temperature differences of the air near the earth cause two kinds of atmospheric motion: convective currents (upward and downward motion) and wind (horizontal motion). Currents and winds are important as they affect takeoff, landing, and cruise flight operations. Most importantly, currents and winds or atmospheric circulation cause weather changes.

Wind Patterns

In the Northern Hemisphere, the flow of air from areas of high to low pressure is deflected to the right and produces a clockwise circulation around an area of high pressure. This is known as anticyclonic circulation. The opposite is true of low-pressure areas; the air flows toward a low and is deflected to create a counterclockwise or cyclonic circulation.

High-pressure systems are generally areas of dry, descending air. Good weather is typically associated with high-pressure systems for this reason. Conversely, air flows into a low pressure area to replace rising air. This air usually brings increasing cloudiness and precipitation. Thus, bad weather is commonly associated with areas of low pressure.

A good understanding of high- and low-pressure wind patterns can be of great help when planning a flight because a pilot can take advantage of beneficial tailwinds. When planning a flight from west to east, favorable winds would be encountered along the northern side of a high-pressure system or the southern side of a low-pressure system. On the return flight, the most favorable winds would be along the southern side of the same high-pressure system or the northern side of a low-pressure system. An added advantage is a better understanding of what type of weather to expect in a given area along a route of flight based on the prevailing areas of highs and lows.

While the theory of circulation and wind patterns is accurate for large scale atmospheric circulation, it does not take into account changes to the circulation on a local scale. Local conditions, geological features, and other anomalies can change the wind direction and speed close to the Earth’s surface.

Convective Currents

Plowed ground, rocks, sand, and barren land absorb solar energy quickly and can therefore give off a large amount of heat; whereas, water, trees, and other areas of vegetation tend to more slowly absorb heat and give off heat. The resulting uneven heating of the air creates small areas of local circulation called convective currents.

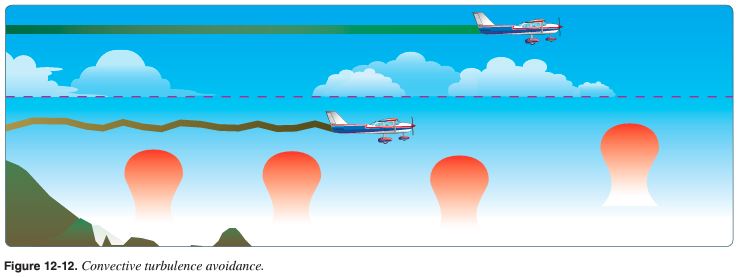

Convective currents cause the bumpy, turbulent air sometimes experienced when flying at lower altitudes during warmer weather. On a low-altitude flight over varying surfaces, updrafts are likely to occur over pavement or barren places, and downdrafts often occur over water or expansive areas of vegetation like a group of trees. Typically, these turbulent conditions can be avoided by flying at higher altitudes, even above cumulus cloud layers. [Figure 12-12]

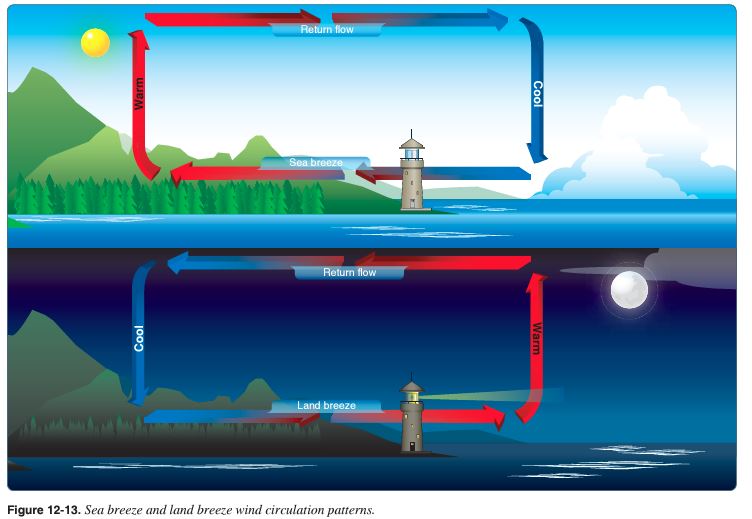

Convective currents are particularly noticeable in areas with a land mass directly adjacent to a large body of water, such as an ocean, large lake, or other appreciable area of water. During the day, land heats faster than water, so the air over the land becomes warmer and less dense. It rises and is replaced by cooler, denser air flowing in from over the water. This causes an onshore wind called a sea breeze. Conversely, at night land cools faster than water, as does the corresponding air. In this case, the warmer air over the water rises and is replaced by the cooler, denser air from the land, creating an offshore wind called a land breeze. This reverses the local wind circulation pattern. Convective currents can occur anywhere there is an uneven heating of the Earth’s surface. [Figure 12-13]

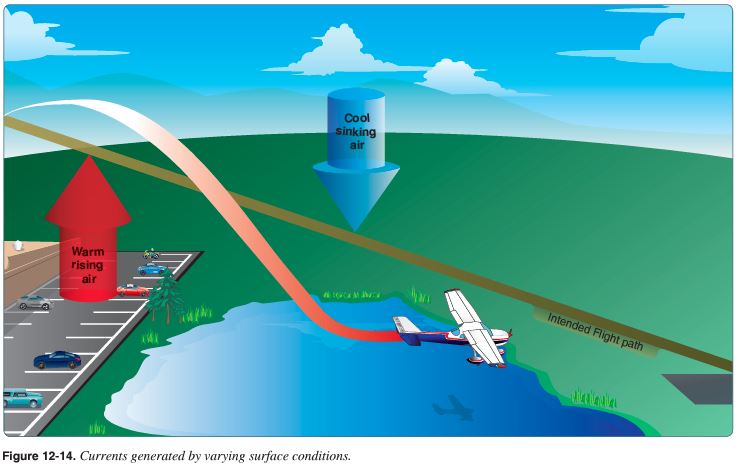

Convective currents close to the ground can affect a pilot’s ability to control the aircraft. For example, on final approach, the rising air from terrain devoid of vegetation sometimes produces a ballooning effect that can cause a pilot to overshoot the intended landing spot. On the other hand, an approach over a large body of water or an area of thick vegetation tends to create a sinking effect that can cause an unwary pilot to land short of the intended landing spot. [Figure 12-14]

Effect of Obstructions on Wind

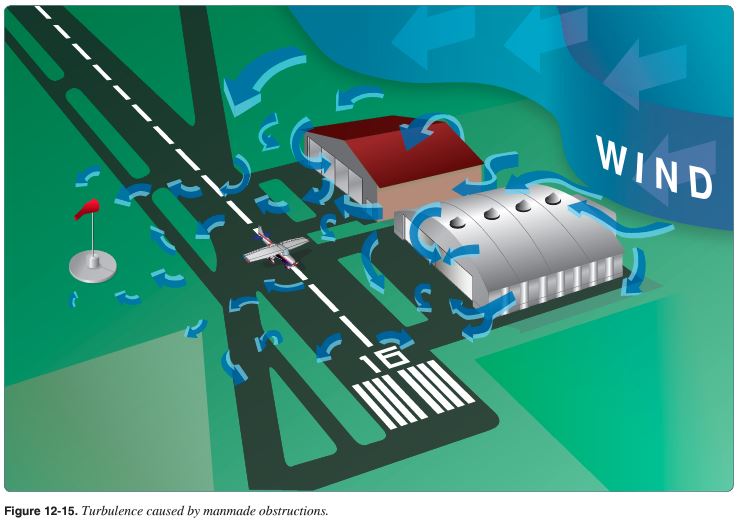

Another atmospheric hazard exists that can create problems for pilots. Obstructions on the ground affect the flow of wind and can be an unseen danger. Ground topography and large buildings can break up the flow of the wind and create wind gusts that change rapidly in direction and speed. These obstructions range from man-made structures, like hangars, to large natural obstructions, such as mountains, bluffs, or canyons. It is especially important to be vigilant when flying in or out of airports that have large buildings or natural obstructions located near the runway. [Figure 12-15]

The intensity of the turbulence associated with ground obstructions depends on the size of the obstacle and the primary velocity of the wind. This can affect the takeoff and landing performance of any aircraft and can present a very serious hazard. During the landing phase of flight, an aircraft may “drop in” due to the turbulent air and be too low to clear obstacles during the approach.

This same condition is even more noticeable when flying in mountainous regions. [Figure 12-16] While the wind flows smoothly up the windward side of the mountain and the upward currents help to carry an aircraft over the peak of the mountain, the wind on the leeward side does not act in a similar manner. As the air flows down the leeward side of the mountain, the air follows the contour of the terrain and is increasingly turbulent. This tends to push an aircraft into the side of a mountain. The stronger the wind, the greater the downward pressure and turbulence become.

Due to the effect terrain has on the wind in valleys or canyons, downdrafts can be severe. Before conducting a flight in or near mountainous terrain, it is helpful for a pilot unfamiliar with a mountainous area to get a checkout with a mountain qualified flight instructor.

UA.III.B.K1c Atmospheric stability, pressure, and temperature (FAA-H-8083-25 Ch. 12)

Atmospheric Stability

The stability of the atmosphere depends on its ability to resist vertical motion. A stable atmosphere makes vertical movement difficult, and small vertical disturbances dampen out and disappear. In an unstable atmosphere, small vertical air movements tend to become larger, resulting in turbulent airflow and convective activity. Instability can lead to significant turbulence, extensive vertical clouds, and severe weather.

Rising air expands and cools due to the decrease in air pressure as altitude increases. The opposite is true of descending air; as atmospheric pressure increases, the temperature of descending air increases as it is compressed. Adiabatic heating and adiabatic cooling are terms used to describe this temperature change.

The adiabatic process takes place in all upward and downward moving air. When air rises into an area of lower pressure, it expands to a larger volume. As the molecules of air expand, the temperature of the air lowers. As a result, when a parcel of air rises, pressure decreases, volume increases, and temperature decreases. When air descends, the opposite is true. The rate at which temperature decreases with an increase in altitude is referred to as its lapse rate. As air ascends through the atmosphere, the average rate of temperature change is 2 °C (3.5 °F) per 1,000 feet.

Since water vapor is lighter than air, moisture decreases air density, causing it to rise. Conversely, as moisture decreases, air becomes denser and tends to sink. Since moist air cools at a slower rate, it is generally less stable than dry air since the moist air must rise higher before its temperature cools to that of the surrounding air. The dry adiabatic lapse rate (unsaturated air) is 3 °C (5.4 °F) per 1,000 feet. The moist adiabatic lapse rate varies from 1.1 °C to 2.8 °C (2 °F to 5 °F) per 1,000 feet.

The combination of moisture and temperature determine the stability of the air and the resulting weather. Cool, dry air is very stable and resists vertical movement, which leads to good and generally clear weather. The greatest instability occurs when the air is moist and warm, as it is in the tropical regions in the summer. Typically, thunderstorms appear on a daily basis in these regions due to the instability of the surrounding air.

Inversion

As air rises and expands in the atmosphere, the temperature decreases. There is an atmospheric anomaly that can occur; however, that changes this typical pattern of atmospheric behavior. When the temperature of the air rises with altitude, a temperature inversion exists. Inversion layers are commonly shallow layers of smooth, stable air close to the ground. The temperature of the air increases with altitude to a certain point, which is the top of the inversion. The air at the top of the layer acts as a lid, keeping weather and pollutants trapped below. If the relative humidity of the air is high, it can contribute to the formation of clouds, fog, haze, or smoke resulting in diminished visibility in the inversion layer.

Surface-based temperature inversions occur on clear, cool nights when the air close to the ground is cooled by the lowering temperature of the ground. The air within a few hundred feet of the surface becomes cooler than the air above it. Frontal inversions occur when warm air spreads over a layer of cooler air, or cooler air is forced under a layer of warmer air.

Moisture and Temperature

The atmosphere, by nature, contains moisture in the form of water vapor. The amount of moisture present in the atmosphere is dependent upon the temperature of the air. Every 20 °F increase in temperature doubles the amount of moisture the air can hold. Conversely, a decrease of 20 °F cuts the capacity in half.

Water is present in the atmosphere in three states: liquid, solid, and gaseous. All three forms can readily change to another, and all are present within the temperature ranges of the atmosphere. As water changes from one state to another, an exchange of heat takes place. These changes occur through the processes of evaporation, sublimation, condensation, deposition, melting, or freezing. However, water vapor is added into the atmosphere only by the processes of evaporation and sublimation.

Evaporation is the changing of liquid water to water vapor. As water vapor forms, it absorbs heat from the nearest available source. This heat exchange is known as the latent heat of evaporation. A good example is the evaporation of human perspiration. The net effect is a cooling sensation as heat is extracted from the body. Similarly, sublimation is the changing of ice directly to water vapor, completely bypassing the liquid stage. Though dry ice is not made of water, but rather carbon dioxide, it demonstrates the principle of sublimation when a solid turns directly into vapor.

Relative Humidity

Humidity refers to the amount of water vapor present in the atmosphere at a given time. Relative humidity is the actual amount of moisture in the air compared to the total amount of moisture the air could hold at that temperature. For example, if the current relative humidity is 65 percent, the air is holding 65 percent of the total amount of moisture that it is capable of holding at that temperature and pressure. While much of the western United States rarely sees days of high humidity, relative humidity readings of 75 to 90 percent are not uncommon in the southern United States during warmer months.

Temperature/Dew Point Relationship

The relationship between dew point and temperature defines the concept of relative humidity. The dew point, given in degrees, is the temperature at which the air can hold no more moisture. When the temperature of the air is reduced to the dew point, the air is completely saturated and moisture begins to condense out of the air in the form of fog, dew, frost, clouds, rain, or snow.

As moist, unstable air rises, clouds often form at the altitude where temperature and dew point reach the same value. When lifted, unsaturated air cools at a rate of 5.4 °F per 1,000 feet and the dew point temperature decreases at a rate of 1 °F per 1,000 feet. This results in a convergence of temperature and dew point at a rate of 4.4 °F. Apply the convergence rate to the reported temperature and dew point to determine the height of the cloud base.

Dew and Frost

On cool, clear, calm nights, the temperature of the ground and objects on the surface can cause temperatures of the surrounding air to drop below the dew point. When this occurs, the moisture in the air condenses and deposits itself on the ground, buildings, and other objects like cars and aircraft. This moisture is known as dew and sometimes can be seen on grass and other objects in the morning. If the temperature is below freezing, the moisture is deposited in the form of frost. While dew poses no threat to an aircraft, frost poses a definite flight safety hazard. Frost disrupts the flow of air over the wing and can drastically reduce the production of lift. It also increases drag, which when combined with lowered lift production, can adversely affect the ability to take off. An aircraft must be thoroughly cleaned and free of frost prior to beginning a flight.

UA.III.B.K1d Air masses and fronts (FAA-H-8083-25 Ch. 12)

Air Masses

Air masses are classified according to the regions where they originate. They are large bodies of air that take on the characteristics of the surrounding area or source region. A source region is typically an area in which the air remains relatively stagnant for a period of days or longer. During this time of stagnation, the air mass takes on the temperature and moisture characteristics of the source region. Areas of stagnation can be found in polar regions, tropical oceans, and dry deserts. Air masses are generally identified as polar or tropical based on temperature characteristics and maritime or continental based on moisture content.

A continental polar air mass forms over a polar region and brings cool, dry air with it. Maritime tropical air masses form over warm tropical waters like the Caribbean Sea and bring warm, moist air. As the air mass moves from its source region and passes over land or water, the air mass is subjected to the varying conditions of the land or water which modify the nature of the air mass.

An air mass passing over a warmer surface is warmed from below, and convective currents form, causing the air to rise. This creates an unstable air mass with good surface visibility. Moist, unstable air causes cumulus clouds, showers, and turbulence to form.

Conversely, an air mass passing over a colder surface does not form convective currents but instead creates a stable air mass with poor surface visibility. The poor surface visibility is due to the fact that smoke, dust, and other particles cannot rise out of the air mass and are instead trapped near the surface. A stable air mass can produce low stratus clouds and fog.

Fronts

As an air mass moves across bodies of water and land, it eventually comes in contact with another air mass with different characteristics. The boundary layer between two types of air masses is known as a front. An approaching front of any type always means changes to the weather are imminent.

There are four types of fronts that are named according to the temperature of the advancing air relative to the temperature of the air it is replacing: [Figure 12-24]

• Warm

• Cold

• Stationary

• Occluded

Any discussion of frontal systems must be tempered with the knowledge that no two fronts are the same. However, generalized weather conditions are associated with a specific type of front that helps identify the front.

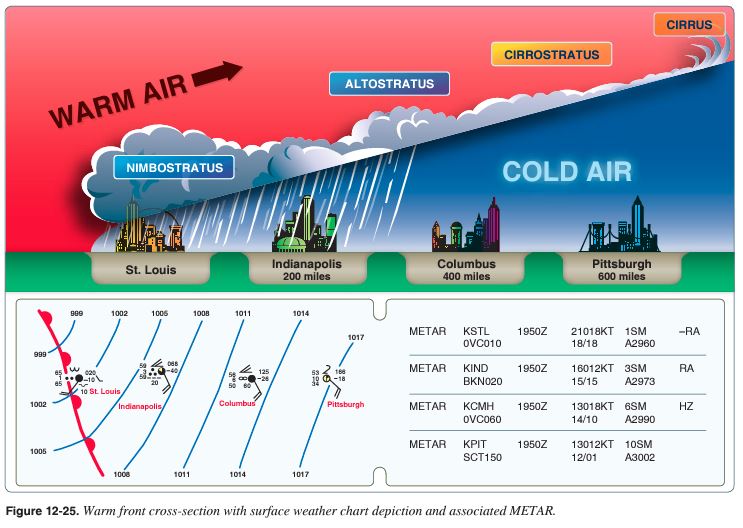

Warm Front

A warm front occurs when a warm mass of air advances and replaces a body of colder air. Warm fronts move slowly, typically 10 to 25 miles per hour (mph). The slope of the advancing front slides over the top of the cooler air and gradually pushes it out of the area. Warm fronts contain warm air that often has very high humidity. As the warm air is lifted, the temperature drops and condensation occurs.

Generally, prior to the passage of a warm front, cirriform or stratiform clouds, along with fog, can be expected to form along the frontal boundary. In the summer months, cumulonimbus clouds (thunderstorms) are likely to develop.

Light to moderate precipitation is probable, usually in the form of rain, sleet, snow, or drizzle, accentuated by poor visibility. The wind blows from the south-southeast, and the outside temperature is cool or cold with an increasing dew point. Finally, as the warm front approaches, the barometric pressure continues to fall until the front passes completely.

During the passage of a warm front, stratiform clouds are visible and drizzle may be falling. The visibility is generally poor, but improves with variable winds. The temperature rises steadily from the inflow of relatively warmer air. For the most part, the dew point remains steady and the pressure levels off. After the passage of a warm front, stratocumulus clouds predominate and rain showers are possible. The visibility eventually improves, but hazy conditions may exist for a short period after passage. The wind blows from the south southwest. With warming temperatures, the dew point rises and then levels off. There is generally a slight rise in barometric pressure, followed by a decrease of barometric pressure.

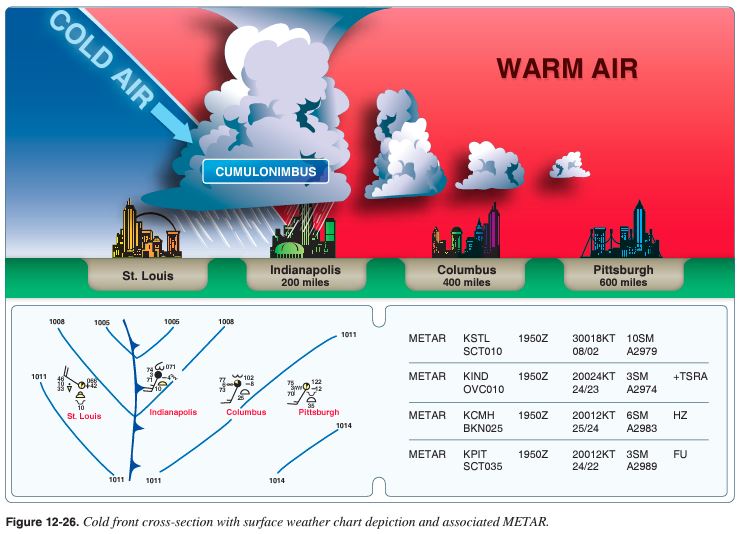

Cold Front

A cold front occurs when a mass of cold, dense, and stable air advances and replaces a body of warmer air.

Cold fronts move more rapidly than warm fronts, progressing at a rate of 25 to 30 mph. However, extreme cold fronts have been recorded moving at speeds of up to 60 mph. A typical cold front moves in a manner opposite that of a warm front. It is so dense, it stays close to the ground and acts like a snowplow, sliding under the warmer air and forcing the less dense air aloft. The rapidly ascending air causes the temperature to decrease suddenly, forcing the creation of clouds. The type of clouds that form depends on the stability of the warmer air mass. A cold front in the Northern Hemisphere is normally oriented in a northeast to southwest manner and can be several hundred miles long, encompassing a large area of land.

Prior to the passage of a typical cold front, cirriform or towering cumulus clouds are present, and cumulonimbus clouds may develop. Rain showers may also develop due to the rapid development of clouds. A high dew point and falling barometric pressure are indicative of imminent cold front passage.

As the cold front passes, towering cumulus or cumulonimbus clouds continue to dominate the sky. Depending on the intensity of the cold front, heavy rain showers form and may be accompanied by lightning, thunder, and/or hail. More severe cold fronts can also produce tornadoes. During cold front passage, the visibility is poor with winds variable and gusty, and the temperature and dew point drop rapidly. A quickly falling barometric pressure bottoms out during frontal passage, then begins a gradual increase.

After frontal passage, the towering cumulus and cumulonimbus clouds begin to dissipate to cumulus clouds with a corresponding decrease in the precipitation. Good visibility eventually prevails with the winds from the west northwest. Temperatures remain cooler and the barometric pressure continues to rise.

Fast-Moving Cold Front

Fast-moving cold fronts are pushed by intense pressure systems far behind the actual front. The friction between the ground and the cold front retards the movement of the front and creates a steeper frontal surface. This results in a very narrow band of weather, concentrated along the leading edge of the front. If the warm air being overtaken by the cold front is relatively stable, overcast skies and rain may occur for some distance behind the front. If the warm air is unstable, scattered thunderstorms and rain showers may form. A continuous line of thunderstorms, or squall line, may form along or ahead of the front. Squall lines present a serious hazard to pilots as squall-type thunderstorms are intense and move quickly. Behind a fast-moving cold front, the skies usually clear rapidly, and the front leaves behind gusty, turbulent winds and colder temperatures.

Wind Shifts

Wind around a high-pressure system rotates clockwise, while low-pressure winds rotate counter-clockwise. When two high pressure systems are adjacent, the winds are almost in direct opposition to each other at the point of contact. Fronts are the boundaries between two areas of high pressure, and therefore, wind shifts are continually occurring within a front. Shifting wind direction is most pronounced in conjunction with cold fronts.

Stationary Front

When the forces of two air masses are relatively equal, the boundary or front that separates them remains stationary and influences the local weather for days. This front is called a stationary front. The weather associated with a stationary front is typically a mixture that can be found in both warm and cold fronts.

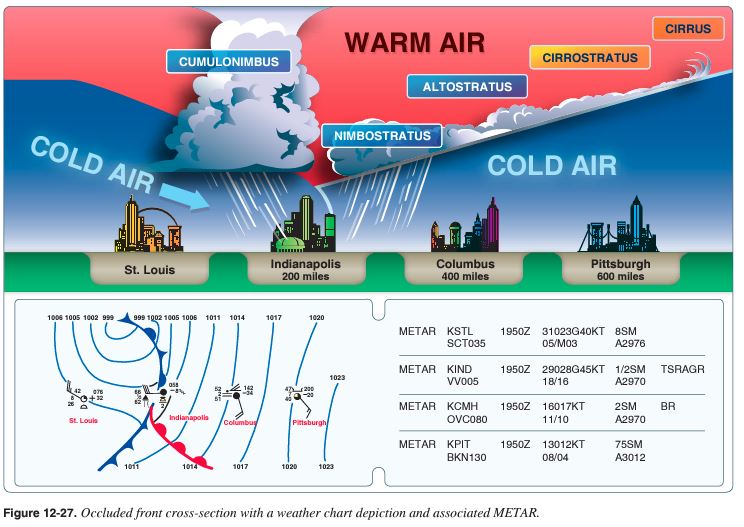

Occluded Front

An occluded front occurs when a fast-moving cold front catches up with a slow-moving warm front. As the occluded front approaches, warm front weather prevails but is immediately followed by cold front weather. There are two types of occluded fronts that can occur, and the temperatures of the colliding frontal systems play a large part in defining the type of front and the resulting weather. A cold front occlusion occurs when a fast moving cold front is colder than the air ahead of the slow moving warm front. When this occurs, the cold air replaces the cool air and forces the warm front aloft into the atmosphere. Typically, the cold front occlusion creates a mixture of weather found in both warm and cold fronts, providing the air is relatively stable. A warm front occlusion occurs when the air ahead of the warm front is colder than the air of the cold front. When this is the case, the cold front rides up and over the warm front. If the air forced aloft by the warm front occlusion is unstable, the weather is more severe than the weather found in a cold front occlusion. Embedded thunderstorms, rain, and fog are likely to occur.

Figure 12-27 depicts a cross-section of a typical cold front occlusion. The warm front slopes over the prevailing cooler air and produces the warm front type weather. Prior to the passage of the typical occluded front, cirriform and stratiform clouds prevail, light to heavy precipitation falls, visibility is poor, dew point is steady, and barometric pressure drops. During the passage of the front, nimbostratus and cumulonimbus clouds predominate, and towering cumulus clouds may also form. Light to heavy precipitation falls, visibility is poor, winds are variable, and the barometric pressure levels off. After the passage of the front, nimbostratus and altostratus clouds are visible, precipitation decreases, and visibility improves.

UA.III.B.K1e Thunderstorms and microbursts (FAA-H-8083-25 Ch. 12)

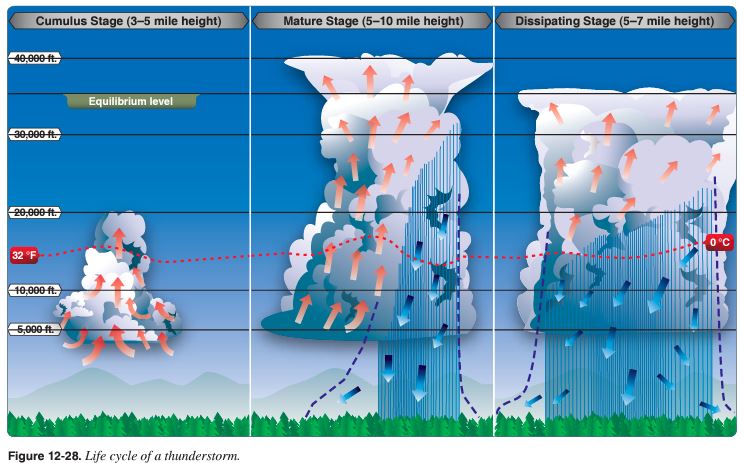

A thunderstorm makes its way through three distinct stages before dissipating. It begins with the cumulus stage, in which lifting action of the air begins. If sufficient moisture and instability are present, the clouds continue to increase in vertical height. Continuous, strong updrafts prohibit moisture from falling. Within approximately 15 minutes, the thunderstorm reaches the mature stage, which is the most violent time period of the thunderstorm’s life cycle. At this point, drops of moisture, whether rain or ice, are too heavy for the cloud to support and begin falling in the form of rain or hail. This creates a downward motion of the air. Warm, rising air; cool, precipitation-induced descending air; and violent turbulence all exist within and near the cloud. Below the cloud, the down-rushing air increases surface winds and decreases the temperature. Once the vertical motion near the top of the cloud slows down, the top of the cloud spreads out and takes on an anvil-like shape. At this point, the storm enters the dissipating stage. This is when the downdrafts spread out and replace the updrafts needed to sustain the storm. [Figure 12-28]

It is impossible to fly over thunderstorms in light aircraft. Severe thunderstorms can punch through the tropopause and reach staggering heights of 50,000 to 60,000 feet depending on latitude. Flying under thunderstorms can subject aircraft to rain, hail, damaging lightning, and violent turbulence. A good rule of thumb is to circumnavigate thunderstorms identified as severe or giving an extreme radar echo by at least 20 nautical miles (NM) since hail may fall for miles outside of the clouds. If flying around a thunderstorm is not an option, stay on the ground until it passes.

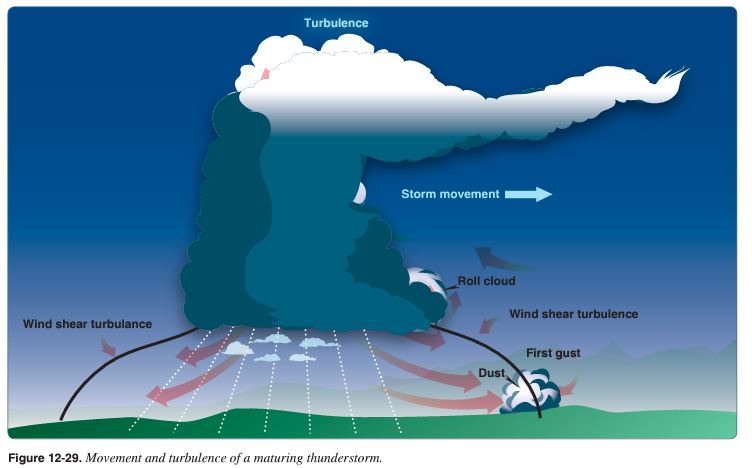

For a thunderstorm to form, the air must have sufficient water vapor, an unstable lapse rate, and an initial lifting action to start the storm process. Some storms occur at random in unstable air, last for only an hour or two, and produce only moderate wind gusts and rainfall. These are known as air mass thunderstorms and are generally a result of surface heating. Steady-state thunderstorms are associated with weather systems. Fronts, converging winds, and troughs aloft force upward motion spawning these storms that often form into squall lines. In the mature stage, updrafts become stronger and last much longer than in air mass storms, hence the name steady state. [Figure 12-29]

Knowledge of thunderstorms and the hazards associated with them is critical to the safety of flight.

UA.III.B.K1f Tornadoes (FAA-H-8083-25 Ch. 12)

The most violent thunderstorms draw air into their cloud bases with great vigor. If the incoming air has any initial rotating motion, it often forms an extremely concentrated vortex from the surface well into the cloud. Meteorologists have estimated that wind in such a vortex can exceed 200 knots with pressure inside the vortex quite low. The strong winds gather dust and debris and the low pressure generates a funnel-shaped cloud extending downward from the cumulonimbus base. If the cloud does not reach the surface, it is a funnel cloud; if it touches a land surface, it is a tornado; and if it touches water, it is a “waterspout.”

Tornadoes occur with both isolated and squall line thunderstorms. Reports for forecasts of tornadoes indicate that atmospheric conditions are favorable for violent turbulence. An aircraft entering a tornado vortex is almost certain to suffer loss of control and structural damage. Since the vortex extends well into the cloud, any pilot inadvertently caught on instruments in a severe thunderstorm could encounter a hidden vortex.

First gust Dust of an approaching storm. Advisory Circular (AC) 00-54, Pilot Windshear Guide, explains gust front hazards associated with thunderstorms. Figure 2 in the AC shows a cross section of a mature stage thunderstorm with a gust front area where very serious turbulence may be encountered. Icing Families of tornadoes have been observed as appendages of the main cloud extending several miles outward from the area of lightning and precipitation. Thus, any cloud connected to a severe thunderstorm carries a threat of violence.

UA.III.B.K1g Icing (FAA-H-8083-25 Ch. 12)

Updrafts in a thunderstorm support abundant liquid water with relatively large droplet sizes. When carried above the freezing level, the water becomes supercooled. When temperature in the upward current cools to about –15 °C, much of the remaining water vapor sublimates as ice crystals. Above this level, at lower temperatures, the amount of supercooled water decreases.

Supercooled water freezes on impact with an aircraft. Clear icing can occur at any altitude above the freezing level, but at high levels, icing from smaller droplets may be rime or mixed rime and clear ice. The abundance of large, supercooled water droplets makes clear icing very rapid between 0 °C and –15 °C and encounters can be frequent in a cluster of cells. Thunderstorm icing can be extremely hazardous.

Thunderstorms are not the only area where pilots could encounter icing conditions. Pilots should be alert for icing anytime the temperature approaches 0 °C and visible moisture is present.

UA.III.B.K1h Hail (FAA-H-8083-25 Ch. 12)

Hail competes with turbulence as the greatest thunderstorm hazard to aircraft. Supercooled drops above the freezing level begin to freeze. Once a drop has frozen, other drops latch on and freeze to it, so the hailstone grows—sometimes into a huge ice ball. Large hail occurs with severe thunderstorms with strong updrafts that have built to great heights. Eventually, the hailstones fall, possibly some distance from the storm core. Hail may be encountered in clear air several miles from thunderstorm clouds.

As hailstones fall through air whose temperature is above 0 °C, they begin to melt and precipitation may reach the ground as either hail or rain. Rain at the surface does not mean the absence of hail aloft. Possible hail should be anticipated with any thunderstorm, especially beneath the anvil of a large cumulonimbus. Hailstones larger than one-half inch in diameter can significantly damage an aircraft in a few seconds.

UA.III.B.K1i Fog (FAA-H-8083-25 Ch. 12)

Fog is a cloud that is on the surface. It typically occurs when the temperature of air near the ground is cooled to the air’s dew point. At this point, water vapor in the air condenses and becomes visible in the form of fog. Fog is classified according to the manner in which it forms and is dependent upon the current temperature and the amount of water vapor in the air.

On clear nights, with relatively little to no wind present, radiation fog may develop. [Figure 12-21] Usually, it forms in low-lying areas like mountain valleys. This type of fog occurs when the ground cools rapidly due to terrestrial radiation, and the surrounding air temperature reaches its dew point. As the sun rises and the temperature increases, radiation fog lifts and eventually burns off. Any increase in wind also speeds the dissipation of radiation fog. If radiation fog is less than 20 feet thick, it is known as ground fog.

When a layer of warm, moist air moves over a cold surface, advection fog is likely to occur. Unlike radiation fog, wind is required to form advection fog. Winds of up to 15 knots allow the fog to form and intensify; above a speed of 15 knots, the fog usually lifts and forms low stratus clouds. Advection fog is common in coastal areas where sea breezes can blow the air over cooler landmasses.

Upslope fog occurs when moist, stable air is forced up sloping land features like a mountain range. This type of fog also requires wind for formation and continued existence. Upslope and advection fog, unlike radiation fog, may not burn off with the morning sun but instead can persist for days. They can also extend to greater heights than radiation fog.

Steam fog, or sea smoke, forms when cold, dry air moves over warm water. As the water evaporates, it rises and resembles smoke. This type of fog is common over bodies of water during the coldest times of the year. Low-level turbulence and icing are commonly associated with steam fog.

Ice fog occurs in cold weather when the temperature is much below freezing and water vapor forms directly into ice crystals. Conditions favorable for its formation are the same as for radiation fog except for cold temperature, usually –25 °F or colder. It occurs mostly in the arctic regions but is not unknown in middle latitudes during the cold season.

UA.III.B.K1j Ceiling and visibility (FAA-G-8082-22 pg. 28)

Ceiling

For aviation purposes, a ceiling is the lowest layer of clouds reported as being broken or overcast, or the vertical visibility into an obscuration like fog or haze. Clouds are reported as broken when five eighths to seven-eighths of the sky is covered with clouds. Overcast means the entire sky is covered with clouds. Current ceiling information is reported by the aviation routine weather report (METAR) and automated weather stations of various types.

Visibility

Closely related to cloud cover and reported ceilings is visibility information. Visibility refers to the greatest horizontal distance at which prominent objects can be viewed with the naked eye. Current visibility is also reported in METAR and other aviation weather reports, as well as by automated weather systems. Visibility information, as predicted by meteorologists, is available for a pilot during a preflight weather briefing.

UA.III.B.K1k Lightning (FAA-H-8083-28 22.7.2)

Every thunderstorm produces lightning and thunder by definition. Lightning is a visible electrical discharge produced by a thunderstorm. The discharge may occur within or between clouds, between a cloud and air, between a cloud and the ground, or between the ground and a cloud.

Lightning can damage or disable an aircraft. It can puncture the skin of an aircraft, and it can damage communications and electronic navigational equipment. Lightning has been suspected of igniting fuel vapors causing an explosion; however, serious accidents due to lightning strikes are extremely rare. Nearby lightning can blind the pilot, rendering the pilot momentarily unable to navigate either by instrument or by visual reference. Nearby lightning can also induce permanent errors in the magnetic compass. Lightning discharges, even distant ones, can disrupt radio communications on low and medium frequencies. Though lightning intensity and frequency have no simple relationship to other storm parameters, severe storms, as a rule, have a high frequency of lightning.