20 Working With Places and Things

Jennifer Clary-Lemon; Derek Mueller; and Kate Pantelides

Abstract

“Working With Places and Things” is a chapter from Try This: Research Methods for Writers. The authors argue that understanding where people and things exist helps researchers to contextualize writing situations. The chapter focuses on the possibilities of using archives, conducting site-based observations, and making maps to better understand subjects and rhetorical situations. These fieldwork methods give researchers new ways of answering their research questions by collecting and curating artifacts, and in uncovering the relationships between physical locations, materials, data, and language.

This reading is available below and as a PDF.

So far in this book, we’ve been paying close attention to words and how to do things that are ethical, meaningful, and methodical with them. In Chapter 2, we learned about how using citation systems and institutional reviews are ways of ethically planning for and representing the people and ideas we are working with. In Chapter 3, we talked about affinity and choric worknets, how words on a page can form relationships between people over time, and how words can construct inventive worlds we hadn’t thought about before. In Chapter 4, we introduced coding and analysis and worked on developing a methodical research design that helps us understand the patterns that develop in language. In Chapter 5, we considered how and when to include people in our research. In this chapter, we focus on the where* of working with words and people: where you might find words that matter, where you might go to understand that words happen in particular places and are used by particular people with particular materials, and the wheres you can create in your own primary research that are worth exploring. This chapter will give you some options for deciding if archives, site-based observing, or mapmaking are good choices for you to use to answer the research question(s) you began working with in Chapter 1. Considering these methods might also give rise to new questions you want to work with.

You might be wondering why place matters in writing, or why we should care about things if we are primarily working with words. The short answer is because where people are, and the things they are surrounded by, matter to the kinds of writing they produce and the subjects they care about. Places and things help build a particular rhetorical situation, and those situations create knowledge problems that we, as researchers, might solve. The longer answer might be imagined with a few examples of interesting knowledge problems that emerge when we consider how words are complicated by places and things:

- How safe is the place you live? How does the ability to walk in your neighborhood at certain times of day reinforce or detract from feeling safe? [working with places]

- What happens when we look for a source using the library’s online catalogue compared to walking around and navigating the stacks? [working with places]

- What is the experience of reading an ebook or PDF compared to a printed book? What sights, sounds, feelings, and smells do you associate with each one? [working with things]

- How does it feel to read a recipe and then join a family member or friend in making your favorite dish the way you’ve always eaten it? [working with things]

- What might be the experience of reading love letters between two people who lived a hundred years ago compared to reading a roman- tic textual exchange on someone’s phone today? [working with places and things]

- What changes when you use a nature identification app to learn about local plants or animals and then try to identify the nature around you on a walk to campus or in your neighborhood? [working with places and things]

- How does reading a job preparation manual differ from being on a job site? How are experiences, equipment use, and safety changed by going to a job versus reading about work? [working with places and things]

Each of these situations ask us to consider words in conjunction with places and things—how words are shaped by our experiences with places; how our bodies feel at a desk or perusing shelves; or how a walk in the woods, a meal in a kitchen, or a visit to a job site might impact our feelings about the words we use or the words we read.

Try This: Identifying Campus Trees (60 minutes)

In this chapter, we pay special attention to the way places invoke our senses—sight, sound, touch, smell, taste—and the way involvement of our senses shapes our research. We also look at the role things play in our research questions and research designs as well as the kind of rhetorical weight* they lend to our data as we fully examine our research question.

Methods Can Be Material

If we remember the definition of research methods from Chapter 1, that is, that they are the tools, instruments, practices, and processes that help us answer our research questions, it’s important to recognize that some methods that help us think through and answer those questions are actual things themselves, whether we make them ourselves or use instruments to help us collect our data. Researchers from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds use the process of making using things as a vital part of their research methods. Take, for example, the way that making a textile, like a basket or a quilt, helps give our bodies a particular kind of touch knowledge. When we engage in sharing that basket or quilt with others and observe their reactions to our ef- forts, that gives us a certain kind of affective, embodied, or feeling-knowledge. It is possible that the only way to really answer a research question about how baskets or quilts make us feel or what significance they have for a community is by engaging in the material making. Thus, even seemingly ordinary practices like basket making or quilting can be a research method if they help provide knowledge about a research question.

Similarly, working with instruments as things helps us extend our knowledge to answer research questions in different ways. Perhaps, after trying to identify trees on your campus using all of your senses, you are interested in trees and the different ways they make us feel about the environments we live in. As a continuation of the “Try This” that invites you to explore campus grounds with particular attention to trees, you might move forward in such an investigation with a campus tree survey, even using satellite maps to locate where all of the trees are on your campus and visiting and taking pictures at each of those places to count how many trees exist where you spend so much time each day (see Chapter 7). Following your making of a campus tree survey, even if limited to a small section of campus, you might then, as part of your research design (see Chapter 5), create a questionnaire about how people feel about nature on campus. You also might look at the way researchers have used a variety of instruments and tools to measure this same phenomenon, for example through the use of small microphones and surface transducers (speakers) embedded in the bark of trees to give rise to projects like the ListenTree project (listentree.media.mit.edu/), in which people can listen to the sonic vibrations trees make in forests, or the Danish Living Tree project (airlab.itu.dk/the-living-tree), in which researchers placed small, hidden speakers in trees to allow people around them to listen differently to the life of trees represented sonically: the sounds of insects crawling, or the tree “breathing” as people get closer to it. In those particular cases, things—both instruments (microphones and speaker) and non-humans (trees)—help us understand different facets of the research question in ways that reading a literature review about the coniferous and deciduous trees in our area might not. It’s important to recognize that research methods engage places, things, and texts in sometimes complicated ways and that sometimes texts themselves may be things: images, recordings, and ephemera—those things we never imagine might be collected and given meaning, like ticket stubs, receipts, flyers, buttons, and letters.

Archival Methods

One of the ways that writers conduct primary research is by going to original sources*—sources unlike the secondary sources discussed in Chapter 3, such as books and articles, that we usually find at the library or through a database search. Original sources are singular (one-of-a-kind) and provide first-hand accounts of events. They are also known as primary sources. One of the main places a researcher can find original sources are in archives—collections of materials such as images, texts, or audio and video recordings that are housed in one place and usually catalogued and ordered in a way that helps researchers locate the sources they want to work with. Thus, archival research methods are shaped by considering history and how it can be built out of a collection of things.

There are a few different kinds of archives, and some of them are accessed easily and from the comfort of your own home. Internet or digital archives are growing daily: a quick search will tell you that archival materials are available in their entirety about subjects as varied as literacy narratives (www.thedaln.org/), nature images (desertmuseum.org/center/digital_library.php), or AIDS activism (www.actuporalhistory.org/), to name a few. There are a number of websites devoted to putting many portals of digital archives in one place, notably the Digital Public Library of America (dp.la/).

What distinguishes a digital archive from a physical one is often access: some archives only digitize some content rather than all content, and some digital archives have no real physical home. Physical archives, or traditional archives, are usually housed in brick-and-mortar places: public libraries, universities and colleges, corporations, governments, museums, or historical societies. When they’re grouped together, the sources located in archives are called fonds (pronounced fon), which tells you they are grouped in a specific way by the people—archivists—who put them together. Navigating the fonds is some of the most difficult (and rewarding!) work of archival research, and it often takes more time than other kinds of research. Much as working with a new computer program isn’t intuitive unless you’ve made the program yourself, often you either have to think like someone else to navigate the fonds or let a bit of serendipity lead the way. The most important things to know about conducting archival research are the following: every archive is different and comes with different rules (which are useful to know ahead of time), most archives utilize some kind of finding aid—a description that places the material in context—to help researchers use them, and most archives are staffed with archivists—people who can help you navigate the archives so that you can find what you think you’re looking for. We say “think you’re looking for” because in many cases, archival work is more about what you don’t find when you’re expecting to, or what you do find when you aren’t!

Archival research isn’t an exact science: often materials are labeled differently than you would label them or filed in one of any number of ways (for example, a letter about the Old Faithful geyser between two rangers in a historic Yellowstone Park archive might be filed under the rangers’ names, under “Old Faithful,” or under miscellaneous letters). The key to archival research is being patient, being flexible, and knowing that it may take one or more return trips. Some tips for visiting traditional archives are:

- Research the archives in advance. Sometimes you have to request materials a few days in advance of your arrival or have a special pass to visit them. You can also usually locate the particular finding aids that an archive uses to help you find or request what you’re looking for ahead of time.

- Plan what to bring. Many archives do not allow you to bring computers or cell phones and allow a pencil and paper only for notetaking. How might this affect your research process?

- Know the costs. If you either cannot or are not allowed to take photos of the archival materials, many archives offer printing services, but these often come at a price.

Try This: Working with a Digital Archive (45 minutes)

Locate a digital archive that originates from a place close to where you are—in the same city, state, or region. Find one artifact in the archive (image, text, audio, video) and answer the following questions about it:

- What kind of artifact is it? Who authored it and for what purpose?

- What does the kind of artifact it is tell you about what it contains? How does the artifact type (for example, interview transcript, photograph, or meeting note) give you clues as to what it can contain and what it cannot?

- Why was the artifact created and by whom was it made? What function did/does it serve?

- Who was the intended audience for the artifact? Do you think the creator ever intended you to be viewing the artifact?

- When was the artifact created? What was going on in the world then that could have affected its creation?

- Where was the artifact created? Did it have to travel to be included in the archive? What does that tell you about the artifact?

- What clues from the artifact (words, formality or informality of tone or dress, position of landmarks or commonplaces) help you understand where it comes from?

- Is the artifact unique, or is it one of a series of other artifacts like it? How do you know?

- How reliable is the artifact? How do you know? How would you cite this artifact?

- Who is missing from the artifact, and what might that tell you about the time or place it was made?

- What is your own reaction to the artifact? How does it make you feel? Which of your senses are engaged by the artifact?

- What questions do you have about the artifact?

Once you have generated the answers to these questions, do one of the following:

- Draft a research proposal (see Chapter 1) that creates a research question about this artifact and uses archival research as a method; OR

- Write a rhetorical analysis (see Chapter 4) of this artifact.

A final type of archive is a personal archive—a collection of materials that might be housed with you, a friend, or a relative. Perhaps your grandmother kept a collection of quilting fabric, quilts that she made, and quilting books that is in a box or closet that you know of. Or maybe your aunt has amassed a large assortment of baseball memorabilia including newspaper clippings of her favorite teams, thousands of cards, jerseys, and signed baseballs. It is also conceivable that you have been keeping a written record of your goings-on for the last fifteen years, from report cards to journals to artwork to emails. While cataloguing these personal archives would take far more work than simply going to an archive and using a finding aid, they are rich sources of research that allow you to engage more deeply with the contexts and places that artifacts have emerged from in ways that reading about them in a textbook would not. To that end, what separates an archive from a pile of stuff is the meaning that we give it by curation—the way we select, order, and label items in a way that gives shape to the significance of the collection.

Try This: Identifying a Personal Collection (1 hour)

One part of working with archives is caring for the people you come in contact with, even if you have never met those people who were involved with the artifacts you’ve found—or even if they are long gone. How might you represent in an ethical way an image, a set of correspondence, or a relationship that appears in the archives? It’s important to think of uncovering the primary research of the archives that others may or may not have looked at closely as a way of honoring stories that have been there before we get to them. Whether this means we tell partial stories (perhaps we leave the part about our aunt’s baseball boyfriend out of our archival story), spend time carefully constructing the contexts for artifacts (as in the case of marginalized groups, such as prison inmate records in the New York State Archive, or those records in Ireland’s National Archive of women forced to give babies up for adoption by the Catholic church in the late 1960s), or reflect on our own connection with those we learn from in the archives, it is important to remember that what we find in the archives brings a past place into a present one—and that you are the person responsible for handling those places with care.

Site-Based Observations

Although archival work with artifacts, materials, and things asks that we pay special attention to understanding and piecing together a historical past, site-based observations, often called fieldwork or field methods, emphasize how close reading of sites helps us more deeply engage with a particular present. Site-based observations are an important part of qualitative research because they depend on a researcher’s experience to explain a phenomenon and result in thick description—detailed notes—that help emplace a reader in the research while providing evidence about a particular activity or situation that the researcher has experienced.

Central to site-based observations is selecting a site that will give you more information about your research question than only reading the literature about it will tell you. For example, if you are curious about how often texting gets in the way of a person’s everyday life, you could read studies about technology and distraction to gather some preliminary ideas about it. But if you wanted to generate your own primary research that could help answer that question, you might select a busy campus spot for a certain amount of time—say, two hours—and observe how often texting impacts people’s ability to walk, multitask, cross a street, or interact with others. By writing down what you see in detailed field notes, you will also have observational data that will help you answer your research question.

However, site-based observation isn’t just sitting down and recording what you see. Selection of a site, subjects (or people), activities, and things that you record should have some definable reason behind why those and not others, and it’s important to spend some time thinking about your choices of site before you begin fieldwork. From the example above, where is the best spot for learning about texting and walking? Who is most likely to be engaging in the behavior you wish to observe? Why is the activity and site you’ve chosen the best representative of what you’re trying to explore—for example, why use site-based observation when you might instead survey people about texting and distraction? What assumptions do you already have about texting and distraction that could impact how you represent it in your field notes?

Try This Together: Classroom Site-Based Observation and Comparing Field Notes (45 minutes)

Once you’ve generated some ideas about your chosen site and research question and gathered the permission you need (if you’re working with human subjects; see Chapter 5), it’s time to keep field notes*—detailed observations about your chosen site that will help others have a rich view of a particular place. Field notes depend on your ability to be a close observer of what you see: detail people, places, and things; document sounds, smells, textures, feelings, weather conditions, tastes, colors; and define as closely as you can elements that others might not understand or share (for example, instead of “she wrote slowly” you might write “it took the writer ten minutes to compose her first sentence”). There are a few different ways to keep field notes, but we encourage you to keep a special notebook that is lightweight and portable and that you use only for site-based observations.

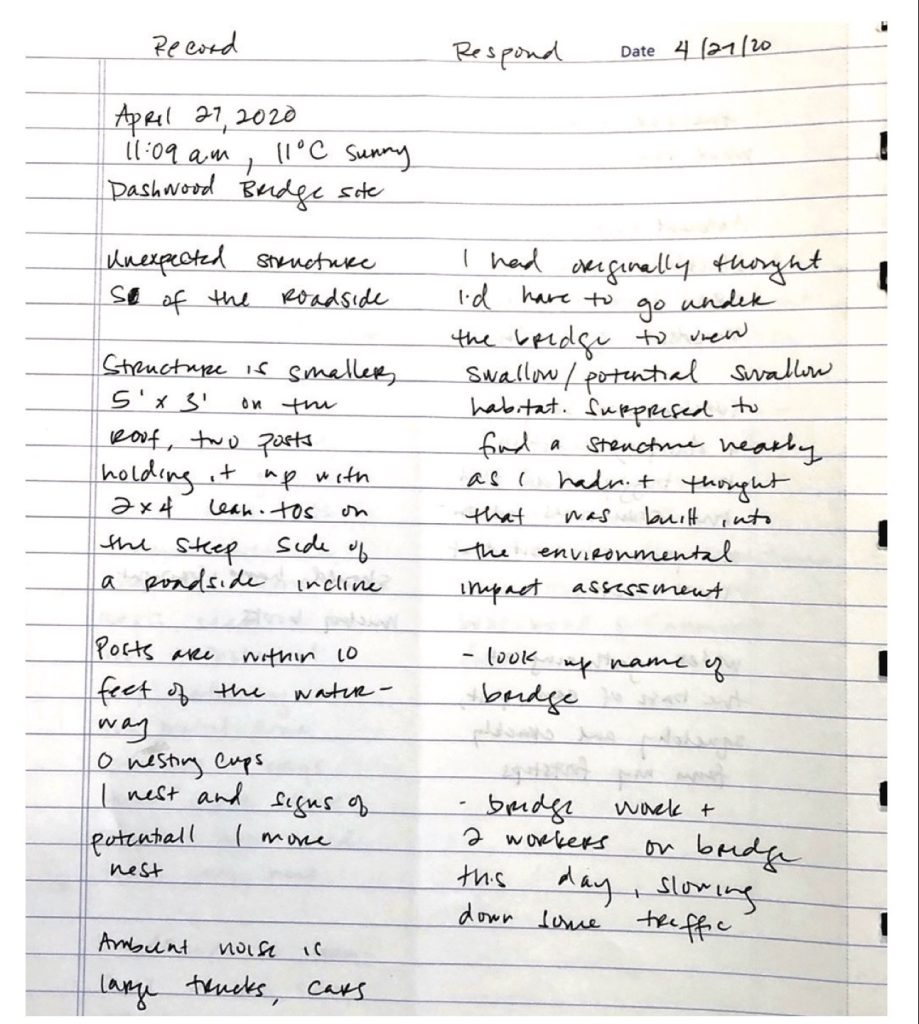

Many site-based observations take the form of a double-entry journal (see Figure 6.1) that in some way splits your notes into two columns, one side that documents an informational record of what is happening, and the other side that contains a more personal response to what is happening. These might be split and labeled “information” and “personal” or “record” and “response,” and they are a good way to begin to think about the difference between what is happening and what you feel about what is happening around you.

But once you delve into a site, especially if you return to the same site more than once, you’ll need to develop your own system for detailing, documenting, and defining what you see. Often there is so much happening in a place that it is difficult to know where to begin notetaking: Which conversation soundbyte is important? Does the weather or the time of day matter? What happens if you’re feeling sick that day on the site? Because every site is filled with rich detail, and every researcher might take different field notes about the same moment, it’s important for you to develop a system for your note taking that will help you later connect your observations to your research question. We suggest that whatever form your field notes take, you aim for the following:

- Accuracy: record the same kinds of information during every observational visit (date, time, location).

- Detail: record the who, what, where of every visit (conversation bits, room or site conditions and description, length of time it takes for something to happen).

- Definition: be as specific as you can about elements around you that would help someone unfamiliar with the site understand what is happening.

- Sensation and Response: make note of specific ways your body feels in the space and which emotions arise.

- Questions: record any questions you are left with while at the site.*

You may well end up with more observational data than you need—but as you go back through your notes, you will begin to see patterns and trends emerging from your observations, much like when you developed your coding scheme for discourse in Chapter 4. As you compose research memos from each site visit (see Chapter 5), certain details will become important as you group similar things together, examine outliers from what you expected, or reflect on your own reactions and feelings to what you saw. All of those ways of assembling information provide evidence for answering your research question and for understanding the way that places shape what happens within them.

Places and Things Converge: Mapmaking as a Method

So far, we’ve discussed some important places where words work to make history (archives) as well as a method for recording the current impacts that places have (site-based observations). Archival research and fieldwork are privileged by researchers in both the humanities and social sciences, but they both make meaning out of observation primarily by using words. As we introduce this final method, mapmaking, we do so not because we expect you to be geographers or cartographers when you graduate, but because sometimes we see relationships and patterns more clearly when we view them spatially and visually, not only verbally or textually. Maps enable us to travel to places we’ve never been, and global satellite imagery allows us to view the world from a bird’s-eye view. For this reason, researchers in many disciplines rely on maps to help them understand, explore, and answer their research questions.

Try This Together: Analyzing Maps (30 minutes)

Making maps helps us see differently. Maps can be used to help us plan information, as in an idea map during pre-writing stages, or they can help us step back from a phenomenon so that we can see patterns and relationships at a distance, as word cloud maps do. Mapping may be part of how we compose field notes in order to orient ourselves or others to our places of research. Mapping as a method is a way of generating data visually and spatially that helps us understand focal points, themes, and hierarchies.

Mapping can also be a way of visualizing location and movement of people and things over time. For instance, let’s say that you’re working with the research question we raised in the beginning of the chapter about the differences and similarities between reading love letters between two people who lived a hundred years ago and reading a romantic textual exchange on someone’s phone today. While you might begin your project with worknets and researching what has been written about the genres of letters and texts, mapping the location and movement of specific letters and texts might give you some different insight about the function of each that could help you answer your research question.

Try This: Map Comparison (45 minutes)

First, hand-draw a map of the trees that you found on or near your campus when you completed the “Try This: Identifying Campus Trees” exercise earlier in this chapter.

Then, consider that the process of moving back and forth between being in a the physical location and looking at a map or satellite view is called ground-truthing among geographers and cartographers. Ground-truthing cares for the ethical coordination of the direct sensory experience (finding trees on campus, as you did) and checking those impressions against the aerial imagery, satellite view, or perhaps a map you have created. Ground-truthing acknowledges that maps, too, warrant ethical consideration and that maps change because the material world changes.

Finally, compare your notes from the “Try This: Identifying Campus Trees” activity with both the map you made and a satellite view of the trees on or near your campus. What is similar? What is different?

Let’s say you’re working with the publicly published letters of lifelong partners Simone de Beauvoir (who lived from 1908-1986) and Jean-Paul Sartre (who lived from 1905-1980), whose correspondence spanned from 1930-1963. Let’s also say you’ll be working with a series of a three-month-long text exchange between you and your romantic partner. There are many ways you could begin to try to answer this research question. On the one hand, you could use some quantitative methods to help you understand these genres of exchange—you might count how many letter exchanges each participant had in each genre and compare the counts, or you might count how many letters were exchanged in three months’ time and compare that number to the number of text messages exchanged in the same amount of time. Or, you might use a qualitative method by reading a sample of letters and texts and creating a coding sheet for discourse analysis (see Chapter 4) that suggests some common (or uncommon) themes that appear in both kinds of exchanges. On the other hand, you might map out these exchanges. You might place each letter in a mapped location of the place where they were at the time they were mailed, which might reveal interesting points of comparison and contrast. Based on your knowledge of where de Beauvoir and Sartre lived between 1930 and 1963, you might find that their correspondence covered the time period of the Second World War and spanned locations throughout France and Germany when Sartre was a prisoner of war. You might also chart where you and your partner lived in the three-month timespan of your exchange, accounting also for the location of text messages in space, pinging off of satellites. In this way, you are creating a location-based, or spatial, map of time travel, distance, and discourse that might help you draw some different kinds of conclusions about letters and texts in the context of a romantic relationship and in the context of the past and present.

Try This: Mapping Movement (60 minutes plus 1 day)

Maps not only help us see differently—in both words and images—but they also can lead us to different kinds of realizations about our research and can exist as important research methods to help us consider elements of distance, scale, scope, and movement. To that end, they should be seen as a complementary method to site-based observations and hold much potential for being included in your field notes. Maps can also help us recognize patterns, themes, or focal points, and they can be created for audiences to help them understand, navigate, or replicate a particular research site or process.

Focus on Delivery: Curating a Collection

Whether you are working with a personal collection, a library archive, or a collection of field notes or maps, inquiry into places and things frequently requires assembling and curating a collection. Curation explores various groupings and patterns, and it often assigns numbering or naming systems so all items in the collection can be referenced. Curated collections aid in making research materials accessible and making patterns discoverable. To help places and things become meaningful in a research context, curate a collection following these steps:

- Select: choose the artifacts you will curate, or identify an existing archive—this can be an old box of stuff, a journal, letters, a drawer of old things, field notes, maps, a digital collection (of pictures, of social media artifacts, of writing, etc.);

- Preserve: take care of your archive—reinforce the box, clean old pictures, back up digital work, label artifacts, and edit the components of your archive;

- Present: collect the work in this archive in a way that will allow you to present it to the class—mount artifacts on a poster, in a book, in a shadow box, etc.; although you’ve selected a personal archive, make sure not to share parts of the archive that you do not want to be public (within the class);

- Analyze: compose an expository, narrative essay highlighting some of the artifacts in this archive and what they tell us about you at that time and place; and

- Reflect: after you’ve composed your essay and developed the presentation of your archive, consider how your work might inform future primary research projects that address archives external to your experience.

Works Cited

Beauvoir, Simone de. Letters to Sartre. Translated and edited by Quintin Hoare, Arcade Publishing, 1993.

Blichfeldt, Malthe Emil, Jonathan Komang-Sønderbek, and Frederik Højlund West- ergård. The Living Tree. Air Lab, IT University of Copenhagen, 2018. airlab.itu.dk/the-living-tree/

Dublon, Gershon, and Edwina Portocarrero. ListenTree. MIT Media Lab, 2015. lis-tentree.media.mit.edu/

Sartre, Jean Paul. Witness to My Life: The Letters of Jean-Paul Sartre to Simone de Beauvoir 1926-1939. Edited by Simone de Beauvoir, Translated by Lee Fahnestock and Norman MacAfee, Penguin, 1994.

Keywords

primary research, site-based observations, observational data, archives

Author Bios

Jennifer Clary-Lemon is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Waterloo. She is the author of Planting the Anthropocene: Rhetorics of Natureculture, Cross Border Networks in Writing Studies (with Mueller, Williams, and Phelps), and co-editor of Decolonial Conversations in Posthuman and New Material Rhetorics (with Grant) and Relations, Locations, Positions: Composition Theory for Writing Teachers (with Vandenberg and Hum). Her research interests include rhetorics of the environment, theories of affect, writing and location, material rhetorics, critical discourse studies, and research methodologies. Her work has been published in Rhetoric Review, Discourse and Society, The American Review of Canadian Studies, Composition Forum, Oral History Forum d’histoire orale, enculturation, and College Composition and Communication.

Derek N. Mueller is Professor of Rhetoric and Writing and Director of the University Writing Program at Virginia Tech. His teaching and research attends to the interplay among writing, rhetorics, and technologies. Mueller regularly teaches courses in visual rhetorics, writing pedagogy, first-year writing, and digital media. He continues to be motivated professionally and intellectually by questions concerning digital writing platforms, networked writing practices, theories of composing, and discipliniographies or field narratives related to writing studies/rhetoric and composition. Along with Andrea Williams, Louise Wetherbee Phelps, and Jen Clary-Lemon, he is co-author of Cross-Border Networks in Writing Studies (Inkshed/Parlor, 2017). His 2018 monograph, Network Sense: Methods for Visualizing a Discipline (in the WAC Clearinghouse #writing series) argues for thin and distant approaches to discerning disciplinary patterns. His other work has been published in College Composition and Communication, Kairos, Enculturation, Present Tense, Computers and Composition, Composition Forum, and JAC.

Kate Lisbeth Pantelides is Associate Professor of English and Director of General Education English at Middle Tennessee State University. Kate’s research examines workplace documents to better understand how to improve written and professional processes, particularly as they relate to equity and inclusion. In the context of teaching, Kate applies this approach to iterative methods of teaching writing to students and teachers, which informs her recent co-authored project, A Theory of Public Higher Education (with Blum, Fernandez, Imad, Korstange, and Laird). Her work has been recognized in The Best of Independent Rhetoric and Composition Journals and circulates in venues such as College Composition and Communication, Composition Studies, Computers and Composition, Inside Higher Ed, Journal of Technical and Professional Writing, and Review of Communication.