8 Developing a Repertoire of Reading Strategies

Ellen C. Carillo

Abstract

Ellen C. Carillo’s essay “Developing a Repertoire of Reading Strategies” comes from her book A Writer’s Guide to Mindful Reading. Her essay offers a collection of reading strategies designed to help students learn to engage in, understand, and respond to various kinds of texts.

This reading is available below and as a PDF.

What Is a Repertoire?

The previous chapter describes the importance of annotating—both as a means to understanding what you read and responding to it. This chapter includes additional strategies for engaging texts. Specifically, this chapter offers you a repertoire of reading strategies. A repertoire is like a collection or catalog, and this chapter shares with you a collection of reading strategies that you can begin to practice as you move through the chapters in this textbook. This chapter is intended to serve as a resource because it is the one place where all of the reading strategies are listed and described. In Part Two you will have the opportunity to apply the reading strategies as you answer questions about and complete assignments related to each chapter’s readings. The more of these strategies you practice and reflect on as you do so, the better prepared you will be to read the range of texts (broadly defined) you will encounter in this class, your other classes, and beyond school. Remember that these strategies may go by different names in different courses and contexts. More important than their names, though, are how they help you understand and respond to what you read. As the descriptions indicate, these strategies are useful across different genres or kinds of texts, as well as across media.

Choosing a Reading Strategy: The Importance of Purpose

As you think about which strategy suits your particular needs, it would be wise to think about your purpose for reading. This is, perhaps, the most important question you must ask yourself. As you consider that question, consider other, related questions. For example:

- Are you reading to then write a summary of the text?

- Are you reading to compare that text to another one?

- Are you reading to see if the text can serve as a source in a research paper?

- Are you reading to design a multimodal project?

- Are you reading to imitate an author’s style?

Determining why you are reading is crucial to choosing the most productive strategy. One strategy might help you understand a text’s argument while another might be more useful in helping you determine a text’s organization or design. Some strategies might work better when you read poetry while others work better with informational texts.

As you practice each strategy, you also need to reflect on it, to think about it. This is the crux of mindful reading—paying close, deliberate attention to how you are reading and how each strategy works. Tracking how well you are reading is not as easy as tracking your writing progress, which can be rather easily done by revising drafts into more polished pieces of writing. This is where annotation comes in. As you apply the reading strategies introduced in this chapter, you are expected to annotate your texts—digitally or by hand—so you can make the very act of reading visible. This will allow you to track your reading, as well as the connections between the practices of writing and reading. Your written annotations will show you what you were thinking and how you were constructing meaning as you were applying each strategy. You might think of your annotations as written drafts of your readings, evidence of preliminary understandings and responses to what you are reading while you are reading. As you apply different reading strategies to the same texts, your annotations will represent articulations of how you interact with the text across multiple experiences of reading.

The Reading Strategies – Previewing

Previewing is one strategy you probably already use, although unconsciously, when you approach both online and printed texts. When you preview a text, you quickly scan it and all that surrounds and supports it. You notice its title, its author, its general design and whether there is an accompanying summary or abstract. You get a sense of its structure, including any subject headings, images, and hyperlinks it may contain. And, ultimately, you determine its genre, which means you decide what type of text it is. You might ask yourself: Is it an informational text or a literary text? Beyond that more general question, you might consider whether it is a piece of poetry, a play, a newspaper article, a blog entry, or a novel. If you determine that the text is a newspaper article, for example, you are going to read it differently than if it were a piece of poetry. In other words, you wouldn’t get very far reading a newspaper article for symbolism and metaphors or reading a piece of poetry simply for information. That is how genre structures your reading.

When you pay attention to genre and these other elements while you are previewing a text, you are paying attention to schemas—elements or frameworks that structure or impact how you read. Schemas depend upon readers drawing on prior knowledge and experiences to help understand what and how the text means. For example, if you read a story that begins with “Once upon a time,” you will—albeit probably unconsciously—recognize that you may be reading a fairy tale. From there, all of the prior knowledge of and experiences you have with fairy tales will kick in, and you will expect to see the elements of a fairy tale in the piece you are reading: the prince and princess; the castle; perhaps a dragon or some other ominous creature; and a happily-ever-after ending. You do a lot of this work unconsciously when you pick up a text or read online. The point is to become more aware of how reading works so you can use this information to make your reading more productive. Keep in mind, though, that it will likely be necessary to use previewing as a preliminary reading strategy and supplement it later with another one that will allow you to more deeply and comprehensively understand what you have read. You apply this strategy by annotating—by marking—the schemas of texts, the aspects that help you understand it.

To experience the power of a schema read the following paragraphs.

The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange things into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere else due to lack of facilities that is the next step, otherwise you are pretty well set. It is important not to overdo things. That is, it is better to do too few things at once than too many. In the short run this may not seem important but complications can easily arise. A mistake can be expensive as well. At first the whole procedure will seem complicated.

Soon, however, it will become just another facet of life. It is difficult to foresee any end to the necessity for this task in the immediate future, but then one never can tell. After the procedure is completed one arranges the materials into different groups again. Then they can be put into their appropriate places. Eventually they will be used once more and the whole cycle will then have to be repeated. However, that is part of life. (Bransford and Johnson 722)

Doesn’t make much sense, does it? In the following example, the same paragraphs are inserted, but with a heading.

Laundry

The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange things into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere else due to lack of facilities that is the next step, otherwise you are pretty well set. It is important not to overdo things. That is, it is better to do too few things at once than too many. In the short run this may not seem important bu complications can easily arise. A mistake can be expensive as well. At first the whole procedure will seem complicated.

Soon, however, it will become just another facet of life. It is difficult to foresee any end to the necessity for this task in the immediate future, but then one never can tell, After the procedure is completed one arranges the materials into different groups again. Then they can be put into their appropriate places. Eventually they will be used once more and the whole cycle will then have to be repeated. However, that is part of life. (Bransford and Johnson 722)

That heading, “Laundry,” acts as a schema that allows you to understand the paragraphs. These excerpts were used in an experiment conducted by cognitive psychologists John D. Bransford and Marcia K. Johnson who found that without that heading as a schema, readers didn’t understand or remember the paragraph. Was that your experience, too?

Skimming

You read right . . . skimming! You might be surprised that you are being encouraged to skim—read quickly—rather than to always read closely or deeply, but skimming is an important reading strategy and is the best reading strategy in some situations. You probably don’t need much instruction in skimming as research shows that this is the most common approach to reading online. Skimming is a lot like previewing and is an appropriate reading practice when you do not need to develop (in your mind) or provide (via a writing assignment) a deep and detailed understanding of a text. Skimming can be a particularly useful practice in the early stages of research when you are looking for sources that are relevant to your topic, but you do not yet need to work closely with them. When you are in the later stages of the writing process of a research essay, if you have determined that it is a useful piece of writing for your purposes, you will need to return and re-read the text using a different reading strategy so that you can work more closely with it in an essay. In other instances, you may not need to do more than skim. As you skim, you may want to annotate a piece by noticing the elements in the following list (some of which involve previewing since the practices are closely related) and marking them as they appear in the text.

- The elements you notice by “previewing” the piece, such as its title; author; introductory mate- rial (e.g. an abstract); and general design and structure (e.g. subject headings, graphics, and hyperlinks). See you if you can determine its genre, which means you decide what type of text it is.

- The introduction since introductions often (although not always) describe the piece as a whole.

- The first sentence of each paragraph since first sentences are usually topic sentences and can give you an overall sense of the subject of the paragraph.

- The conclusion or the final paragraph of the piece since conclusions often (although not always) summarize a piece.

The Says/Does Approach

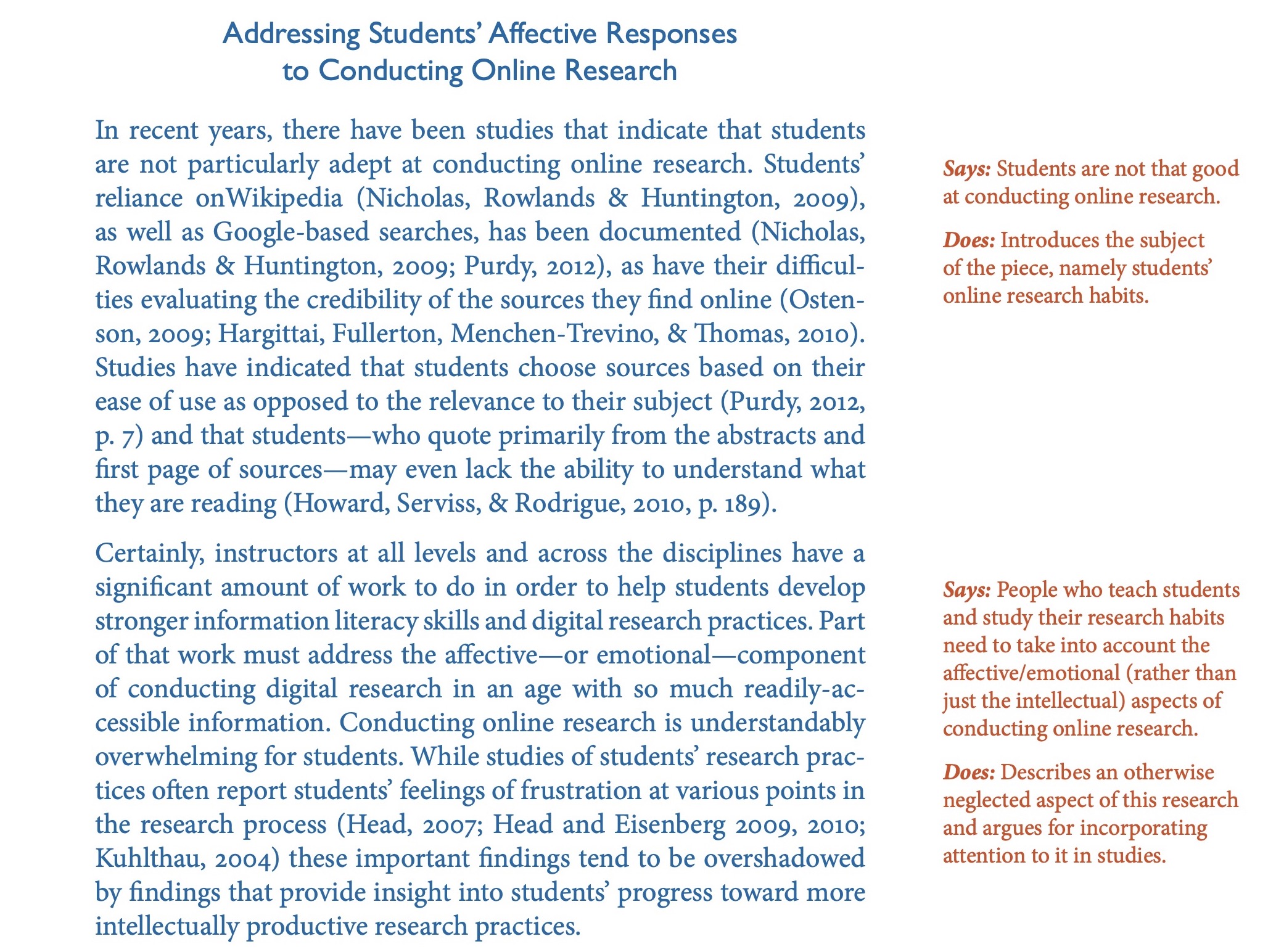

This approach to reading asks you to pay attention to two different elements of any given text. It asks you to notice what the text says—its content—and what the text does—how it functions. This approach is useful because it shifts attention away from content, which is often easier to figure out and toward how a text or sections of a text function. Being able to recognize both what a paragraph (or aspect of a multimodal project) says and what it does—and being able to recognize the difference between the two—can help you understand the piece as a whole. For example, a particularly difficult paragraph in a text you are reading may be addressing the mating habits of bees. That’s the content, the “says” part. In an effort to figure out what that paragraph is doing, you may realize that it is presenting an opposing view that challenges the claim the author is making. In recognizing this, you have avoided the common mistake of attributing all of the ideas within an article to its author. In this case, by focusing on how that paragraph functions, on what it does, you realized that it is not the author speaking, but rather the author is using the example to challenge his own claim. That is what it is doing. This approach can help you determine how the different parts of a text work together to create meaning. When faced with a difficult or especially long text, you can annotate each paragraph by noting what it says and what it does. In the following example, annotations indicate what each paragraph says and does.

Now that you have read the excerpt and its annotations, go back to the annotations to notice the specific verbs used to characterize what each paragraph “does.” This is usually what separates the “says” from the “does” since the “does” is active while the “says” is more descriptive. Let’s go paragraph by paragraph: The first paragraph introduces while the second describes and argues. These verbs—along with other verbs and verb phrases—such as summarizes, challenges, argues, elaborates; supports; narrows the subject; defines; redefines; provides historical context; presents opposing evidence; provides new evidence—will help you define what paragraphs do.

Rhetorical Reading

Rhetorically reading involves reading a text with an eye toward the rhetoric of what you are reading. Rhetoric is the available means of persuasion at a writer’s disposal. When you read something rhetorically you are paying particular attention to how certain elements of the text influence you as you read. By paying attention to those elements as you read, you become more aware of how a text persuades you or acts upon you. This awareness can also help you as a writer make choices about how you will use rhetoric to influence those who read your work, whether it is something you have written or a multimodal project you have created.

When reading rhetorically, there are at least four rhetorical elements to which you should pay attention by asking yourself the following questions about purpose, audience, claims, evidence, and appeals. As you read rhetorically, annotate a text by marking the parts of the piece that help you determine the following:

- What is the author’s purpose? Is the author arguing a point? Bringing awareness to a problem? Trying to make sense of an experience? Calling people to action?

- Who is the intended audience? To whom does the author seem to be writing?

- What are the author’s claims? What claims and what kind of claims does the author make?

- What kinds of evidence are used? Scientific data, anecdotes, personal experience?

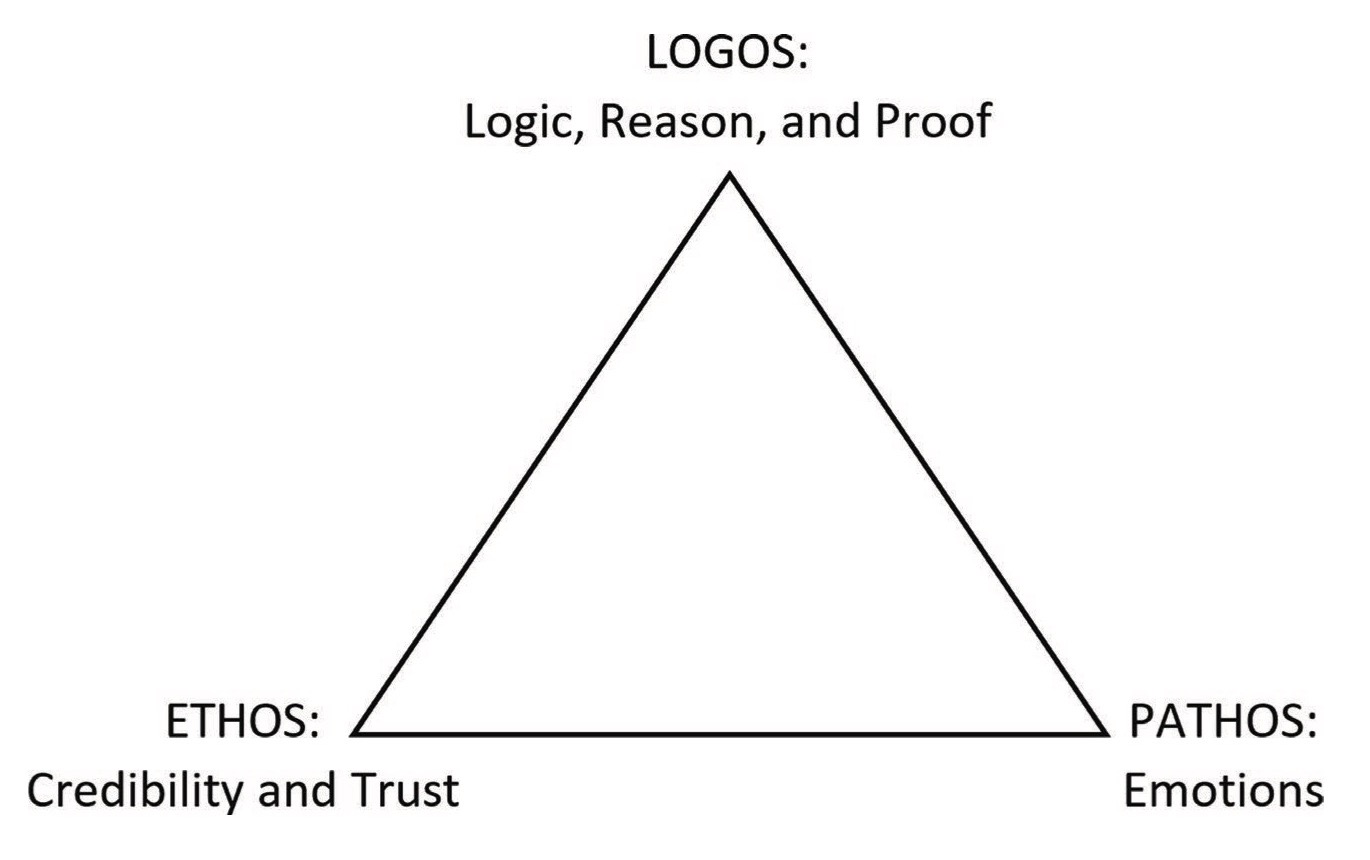

Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle taught his own students that there are three specific types of appeals that orators might make in order to persuade their audiences. These appeals are still taught today as strategies that writers can use to persuade readers and appeals that readers can recognize as ways that texts persuade them. These three persuasive strategies make up the rhetorical triangle.

Ethos: Appeals to credibility. Notice how the author tries to persuade readers by establishing his/her credibility.

Logos: Appeals to logic. Notice how the author uses the logic of his argument or his claims to persuade readers.

Pathos: Appeals to emotions. Notice how the author tries to persuade readers by engaging their emotions.

- Choose any piece of writing—digital or print. You might choose a blog entry, a newspaper, an excerpt from one of your textbooks, or even a piece of your own writing. Rhetorically read it by answering the four questions on the previous page.

- Think of a cause that you believe in (e.g. civil rights; environmental issues; campus issues). Design two flyers advertising the meeting of a campus group that will support the cause. Maybe the cause is something as well-known as global warming or as localized as dorm curfews. The audience for the first flyer is students who have already signed a petition indicating their commitment to the cause. The audience for the second flyer is new, first-year students who likely don’t know about this group on campus. How do these different audiences affect the other rhetorical aspects of your flyers? Look back at the four questions for guidance to determine how the content and the design of the flyers might be impacted by these different audiences.

Reading Aloud to Paraphrase

This strategy really consists of two individual strategies combined into one, namely reading aloud and paraphrasing. You should feel free to separate them if that works better for you. The combination, though, brings together complementary approaches to reading: reading aloud highlights each word as the reader hears it and paraphrase requires that the reader not only hear each word but translate it in her own words. This reading approach, thus, fosters concentration in ways that some others may not, and it may be especially helpful when faced with particularly difficult paragraphs or sections of texts. Unfortunately, many students rarely read aloud beyond elementary school. You may come across a professor who requires you to read poetry aloud, but that is likely the extent of reading aloud in high school and college. Still, if you can recall a time when you heard poetry read aloud (either by yourself or a classmate) it likely made a lot more sense than when you read it on the page. As you read aloud to paraphrase, you need not paraphrase every single word, but you should stop every few sentences or so and annotate the text by writing, in your own words, what you just read.

- Choose a reading from this textbook. Read it aloud, stopping regularly to paraphrase—in the form of annotations—what you are reading. To what extent do these annotations help you understand what you are reading?

- Choose a short piece of nonfiction. First, read it to yourself, and when you are finished write a brief summary of what you have read. Now, read it again aloud, paraphrasing—in the form of annotation—as you read. How were the experiences different?

- If you do not want to read aloud or have difficulty hearing, choose a reading from this textbook and read it to yourself stopping regularly to paraphrase—in the form of annotations—what you are reading. To what extent do these annotations help you understand what you are reading?

Mapping

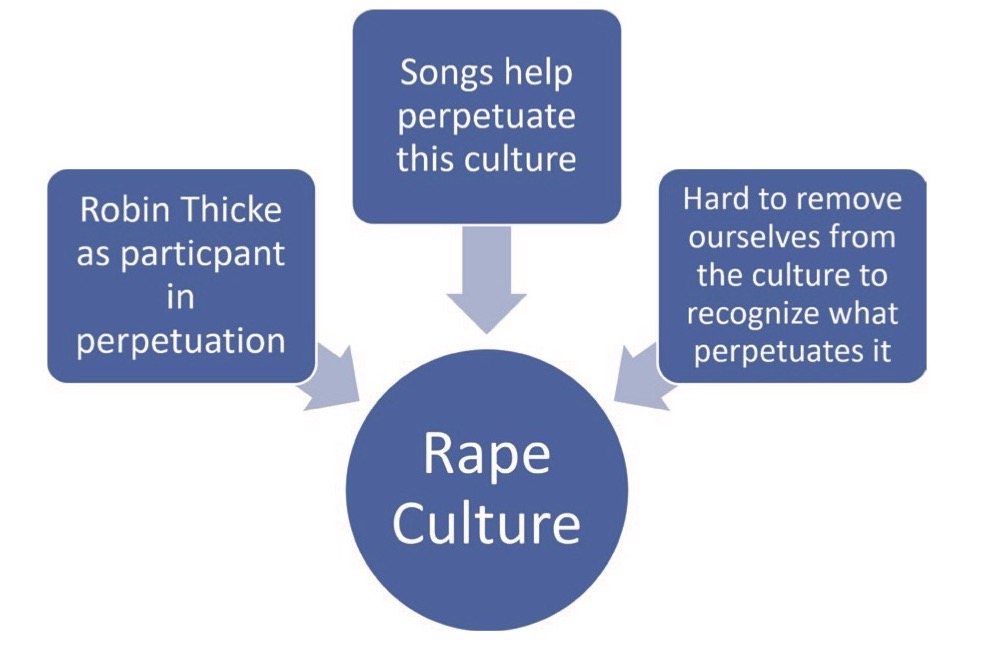

Education scholar and optometrist Héctor C. Santiago, among others, have found that “visual tools may help . . . students develop better recall, comprehension and critical thinking skills” (137). Mapping is one of those visual tools that can be adapted to various reading purposes and helps readers visually organize information. When you map a text you present visually what the text says. You might map the text as a whole, you might choose a few pages to map, or you might choose a single element to map such as a text’s argument. When you map a text, you become highly aware of the relationships among its different parts, and the visual representation often highlights aspects of the text that aren’t otherwise visible.

Maps come in different shapes and sizes, and can be adjusted to suit your needs. Perhaps the most common is the web or radial map in which the main idea or concept is in the center while threads radiate from it to indicate the connections between the central concept/idea and the other, less central ideas. From those threads come other threads and so on from there. Maps can be developed by hand or with digital, text mapping software. The most important element of any map is that it allows you to see how different elements of a text (e.g. its argument, evidence, characters) are related and structured. Often, these visual representations allow you to recognize relationships you hadn’t noticed while reading.

Maps also underscore the importance of returning to and revising your reading as you visually represent, rank, and connect the different elements of the text since you will likely need to revise your map as you continue reading and re-reading. Annotating a text can help you map it because your annotations draw your attention to the various elements of a text you will need to represent visually. The radial map on the following page is based on Sarah Davis’ “‘The Blurred Lines’ Effect: Popular Music and the Perpetuation of Rape Culture” (see Chapter 9 for the full text of Sarah Davis’ essay). By placing the concept of rape culture at the center and related issues around it, the student can begin to visualize some of the ways that rape culture is perpetuated, as well as the challenges of recognizing these forces. It is worth noting that this is a very basic version of a map that would be added to over time as the student sought to further explore the connections among these ideas and others in the text.

Just as this reader would be expected to go back and revise this map in order to incorporate more details, you should imagine that your maps are open to revisions and additions as you read and reread the text you are mapping. Still, this initial map allows you to see how the reader is working toward figuring out what causes and perpetuates rape culture.

The Believing/Doubting Game

This strategy was developed by scholar and teacher Peter Elbow and encourages you, the reader, to play two roles while reading. First, you read a text or engage a project as though you believe it. You annotate the text by marking the reasons why you (in your role as “believer”) would believe these things. You might keep a list in or adjacent to the text and might even add other evidence to the list to further support the writer’s position. Then, you take on the role of the “doubter.” You go back to the text to cast doubt on it. Again, you annotate the text by keeping a running list of the problems or faults you find in the writer’s position. This is an especially useful strategy when you need to figure out where you stand on an issue and what you truly believe in light of what a writer has said. This strategy also helps you understand why others believe what they do since you will have to “believe” a position you may truly doubt.

Reading Like a Writer (RLW)

In 1990, English professor Charles Moran published an essay encouraging students to read like writers. More recently, English professor Mike Bunn extended Moran’s thinking by developing a series of steps that one can take in order to read like a writer, which he often abbreviates as “RLW.” Bunn explains RLW as follows: “When you Read Like a Writer you work to identify some of the choices the author made so that you can better understand how such choices might arise in your own writing. The idea is to carefully examine the things you read, looking at the writerly techniques in the text in order to decide if you might want to adopt similar (or the same) techniques in your writing” (72). Bunn uses the phrase “writerly techniques” to describe the ways that writers present their ideas and make their points. You might think about this as their style. Perhaps the author of the text you are reading has opened her piece with a quotation and concludes with a question. Maybe she switches between formal and informal language throughout. Perhaps she includes dialogue. The key to RLW is noticing these different techniques in order to determine whether you might try them in your own writing. Bunn further explains that this reading approach is not about learning or understanding the content of a reading. Instead, when you adopt this approach you do so to learn about writing. Bunn lists many questions one might ask while using this reading strategy, and he recommends keeping a pen or pencil nearby and marking—or annotating— moments in the text that reveal especially interesting choices that the writer has made. Bunn suggests answering the following central questions about each moment:

- What is the technique the author is using here?

- Is this technique effective?

- What would be the advantages and disadvantages if I tried this same technique in my writing? (81)

Note that these three questions are equally relevant to “reading” multimodal projects, although Bunn’s focus is on print-based work. Keep in mind that while you may not be able to use the technical names all of the different techniques the writer is using, this strategy makes these techniques visible, and, therefore, they can still be imitated. This reading strategy might be especially useful if you are expected to use writing techniques or design techniques similar to those used by another author, as well as if you are looking for new techniques to try out in your own work.

Reading and Evaluating Online Sources

Reading online often involves using search engines and other tools on the internet to search for texts. Because there is so much information—so much to read—online and none of it is regulated in any way, reading online means being especially vigilant about the quality of what you encounter. This reading strategy, then, is not about helping you understand a text’s content, but rather “reading” its credibility—determining whether it is worthy of being believed—so that you can make informed decisions about whether it is a text that will serve your purposes. When faced with online texts— whether digital texts that may have a printed, hardcopy counterpart or websites—evaluate the text by keeping the following questions in mind to gain insight into whether it is an appropriate source for your needs. You may use annotation as a tool for recording your answers.

- Consider the differences among these domains. What kind of website does the text appear on? Is it a .com, .org, .gov, .edu?

- Know the author. Who is the author, organization, or company that sponsors the website? Search for more information once you have this information. If there is no author, try looking up the website at WHOIS, which provides this information: https://whois.icann.org/en

- Try to determine if the piece is peer-reviewed, which means that it goes through an evaluation by other scholars in the field. If you are looking at a journal article, for example, notice the press that publishes the journal. Then search that press to find information about it.

- Look to see if the text has a bibliography at the end. If so, what kinds of texts are cited?

- Consider if any sources are cited in the piece. If so, what kinds?

For Further Reading

Bransford, John D. and Marcia K. Johnson. “Contextual Prerequisites for Understanding: Some Investigations of Comprehension and Recall.” Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, vol. 11, 1972, pp. 717‒726.

Bunn, Mike. “How to Read Like a Writer.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 2, Parlor Press, 2011, pp. 71‒86. http://www.parlorpress.com/pdf/bunn–how-to-read.pdf

Moran, Charles. “Reading Like a Writer.” Vital Signs 1, edited by James L. Collins, Boynton/Cook, 1990, pp. 60‒69.

Santiago, Héctor C. “Visual Mapping to Enhance Learning and Critical Thinking Skills.” Optometric Education, vol. 36, no. 3, 2011, pp. 125‒195.

Keywords

repertoire, reading strategy, schema, rhetorical reading, genre, purpose, previewing, skimming, mapping, ethos, pathos, logos, paraphrase, credible source

Author Bio

Ellen C. Carillo is Associate Professor of English at the University of Connecticut and the Writing Coordinator at its Waterbury Campus. Dr. Carillo is author of Securing a Place for Reading in Composition: The Importance of Teaching for Transfer (Utah State UP, 2015) and her scholarship on reading has appeared in Rhetoric Review; Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture; Reader: Essays in Reader-Oriented Theory, Criticism, and Pedagogy; WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship; The Writing Center Journal; and Currents in Teaching and Learning; as well as in several edited collections. She has also guest-edited a special issue of WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship on the role of reading in writing centers. Dr. Carillo is co-founder of the Role of Reading in Composition Studies Special Interest Group of the Conference on College Composition and Communication and regularly presents her scholarship at regional and national conferences. She has been awarded grants from NeMLA, CCCC, and the Council of Writing Program Administrators.