13 An Introduction to and Strategies for Multimodal Composing

Melanie Gagich

Abstract

In this chapter from Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 3, Melanie Gagich introduces multimodal composing and offers five strategies for creating a multimodal text. The essay begins with a brief review of key terms associated with multimodal composing and provides definitions and examples of the five modes of communication. The first section of the essay also introduces students to the New London Group and offers three reasons why students should consider multimodal composing an important skill—one that should be learned in a writing class. The second half of the essay offers three pre-drafting and two drafting strategies for multimodal composing. Pre-drafting strategies include urging students to consider their rhetorical situation, analyze other multimodal texts, research textual content, gather visual and aural materials, and evaluate tools needed for creating their text. A brief discussion of open licenses and Creative Commons licenses is also included. Drafting strategies include citing and attributing various types of texts appropriately and suggesting that students begin drafting with an outline, script, or visual (depending on the project). Gagich concludes the chapter with suggestions for further reading.

This reading is available below and as a PDF.

Overview

This chapter introduces multimodal composing and offers five strategies for creating a multimodal text. The essay begins with a brief review of key terms associated with multimodal composing and provides definitions and examples of the five modes of communication. The first section of the essay also introduces students to the New London Group and offers three reasons why students should consider multimodal composing an im- portant skill—one that should be learned in a writing class. The second half of the essay offers three pre-drafting and two drafting strategies for multimodal composing. Pre-drafting strategies include urging students to consider their rhetorical situation, analyze other multimodal texts, research textual content, gather visual and aural materials, and evaluate tools needed for creating their text. A brief discussion of open licenses and Creative Commons licenses is also included. Drafting strategies include citing and attributing various types of texts appropriately and suggesting that students begin drafting with an outline, script, or visual (depending on the project). I conclude the chapter with suggestions for further reading.

When you think about a college writing class, you probably think of pens, paper, word processors, printers, and, of course, essay writing. However, on the first day of your college writing class, you might read the syllabus and notice that the first assignment asks you to create a “multimodal text.” You may wonder to yourself, “What does multimodal mean?” Perhaps you remember an assignment from high school when your teacher required you to create a Prezi or PowerPoint presentation, and she referred to it as a “multimodal project,” but you were not exactly sure what that meant. Or perhaps you only remember writing five paragraph essays in high school and have never heard or read the word “multimodal.”

As a first-year and upper-level composition instructor who has integrated a multimodal project into my curriculums since 2014, I have encountered many questions and confusion related to multimodal composing, or what is sometimes referred to as “multimodality.” While some students are thrilled to compose something other than an academic essay, others struggle to understand why they are required to create a multimodal text in a writing class. I assure my students that although they may not be familiar with the concept of multimodality, it has a long history in composition (e.g. writing studies). In fact, the “multimodal assignment” has been a fixture in some college writing classrooms for over a decade and continues to be prevalent in many classrooms. In light of the probability that you will be asked to create a multimodal text at some point in your academic and/or professional career, I wrote this chapter to help you understand and navigate multimodal composing. In the first half of this chapter, I provide brief definitions of terms associated with and explain the importance of multimodal composing. The remainder of the chapter offers strategies for composing a multimodal text with an emphasis on pre-drafting strategies.

What Is a Multimodal Text?

Before moving into a discussion of multimodality and modes of communication, it is important to understand the meaning of the word “text” because it is often only associated with writing (or perhaps the messages you receive or write on your phone). However, when we use the term “text” in composition courses, we often mean it is a piece of communication that can take many forms. For instance, a text is a movie, meme, social media post, essay, website, podcast, and the list goes on. In our daily lives, we encounter, interact with, and consume many types of texts, and it is important to consider how most texts are also multimodal.

Pamela Takayoshi and Cynthia L. Selfe, two important scholars in writing studies and early advocates of multimodal composing, define multimodal texts as “texts that exceed the alphabetical and may include still and moving images, animators, color, words, music, and sound” (1). You’ll notice that the examples of “text” listed above are also multimodal, which demonstrates how often we encounter multimodality in our daily lives. Multimodality is sometimes associated with technology and/or digital writing spaces. For example, when you post an image to Instagram, you use technology (your phone) to snap a picture, an app to edit or modify the image, and a social media platform (Instagram) to share it with others. However, creating a multimodal text does not require the use of digital tools and/or does not need to be shared in online digital spaces to make it “multimodal.” To illustrate, when you create a collage and post it on your dorm room door, you use existing printed artifacts such as pictures clipped and pasted (non-digital technologies) from a magazine and share with others by taping it to your door (a non-digital space). Both examples represent a multimodal text because they include various modes of communication.

The Five Modes of Communication

In the mid-1990s, a group of scholars gathered in New London, New Hampshire and, based on their discussions, wrote the influential article, “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures,” published in 1996. In it, the group advocated for teachers to embrace teaching practices that allow students to draw from five socially and culturally situated modes, or “way[s] of communicating” (Arola, Sheppard, and Ball 1). These modes were linguistic, visual, spatial, gestural, and aural. Yet, scholars such as Claire Lauer, another influential researcher in composition, have argued that the New London Group’s definition of modes, while exceedingly important, can be difficult to grasp. In light of this, below I provide brief definitions of each mode as well as examples to help you understand the “mode” in “multimodal.”

What Are the modes of communication?

The visual mode refers to what an audience can see, such as moving and still images, colors, and alphabetical text size and style. Social media photos (see figure 1) exemplify the visual mode.

The linguistic mode refers to alphabetic text or spoken word. Its emphasis is on language and how words are used (verbally or written). A traditional five paragraph essay relies on the linguistic mode; however, this mode is also apparent in some digital texts. Figure 2 shows a student’s linguistic text included in their website created to promote game-based language learning.

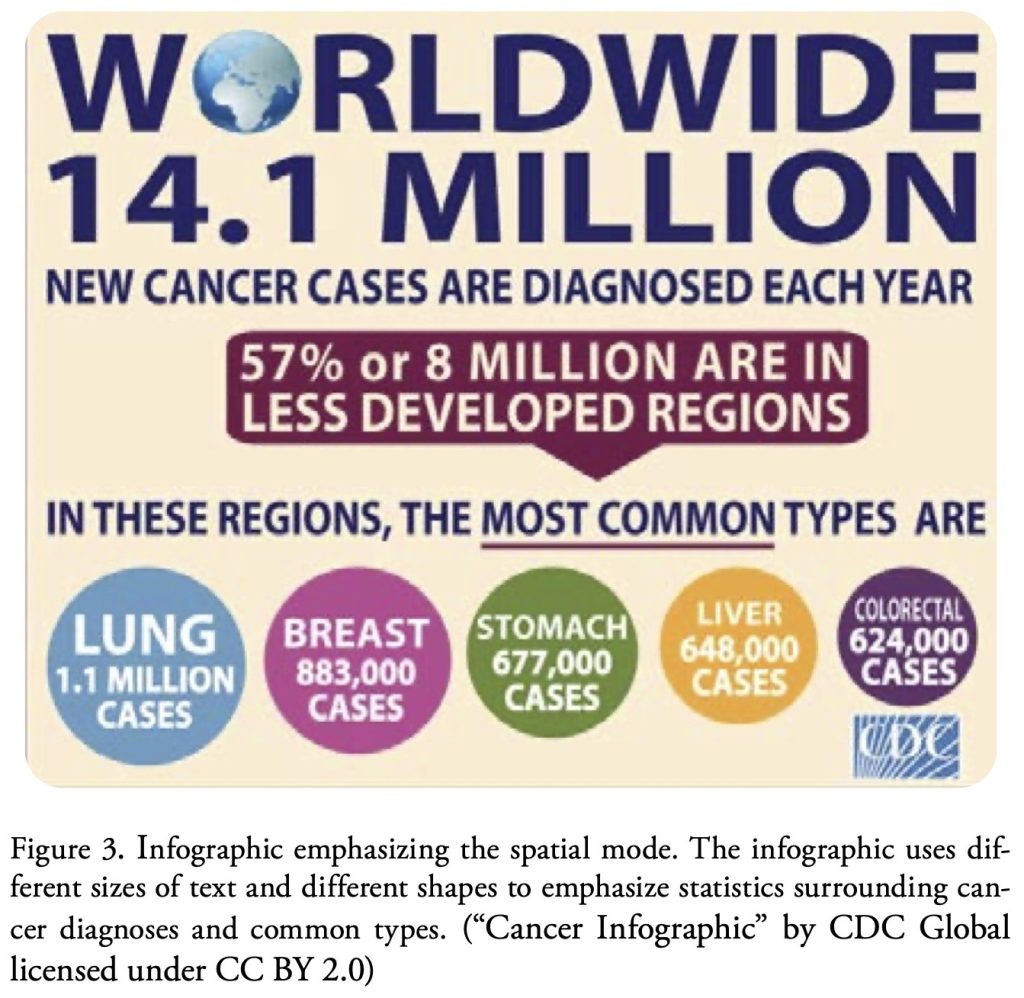

The spatial mode refers to how a text deals with space. This also relates to how other modes are arranged, organized, emphasized, and contrasted in a text. Figure 3, an infographic, is an example of the spatial mode in use because it emphasizes certain percentages and words to achieve its goal.

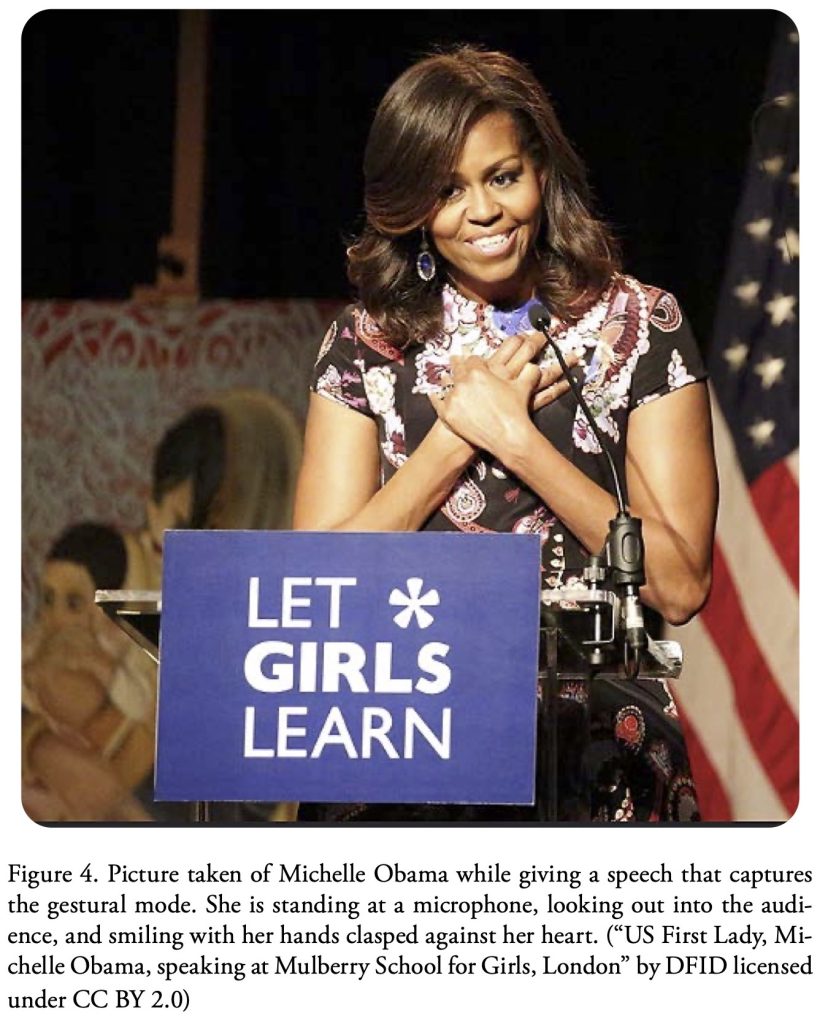

The gestural mode refers to gesture and movement. This mode is often apparent in delivery of speeches in the way(s) that speakers move their hands and fix their facial features and in other texts that capture movement such as videos, movies, and television. Figure 4 shows Michelle Obama’s gestures at a speech she gave in London.

The aural mode refers to what an audience member can or cannot hear. Music is the most obvious representation of the aural mode, but an absence of sound (silence) is also aural. Examples of texts that emphasize the aural mode include podcasts, music videos, concerts, television series, movies, and radio talk shows. Figure 5 is a screenshot of my student’s podcast created to convince teachers to integrate podcasts into their language arts classrooms. A podcast exemplifies the aural mode because of its reliance on sound.

A multimodal text combines various modes of communication (hence the combination of the words “multiple” and “mode” in the term “multi- modal”). Cheryl E. Ball and Colin Charlton draw from The New London Group in their argument that “[a]ny combination of modes makes a multimodal text, and all text—every piece of communication a human composes—use more than one mode. Thus, all writing is multimodal” (42). However, in some communicative texts, one mode receives more emphasis than the others. For example, academia and writing teachers have historically favored the linguistic mode, often seen in the form of the written college essay. Yet, when you communicate using an essay, you are actually using three modes of communication: linguistic, spatial, and visual. The words represent the linguistic mode (the emphasized mode), the margins and spacing characterize the spatial, and the visual mode includes elements like font, font size, or the use of bold.

Combining each mode to create a clear communicative essay often involves the writing process (i.e. invention, drafting, and revision), and a thoughtful writer will also consider how the final product does or does not address an audience. The same process is used when creating a less traditional multimodal text. For instance, when creating a text emphasizing the aural mode (e.g. a podcast), you must consider your audience, purpose, and context while also organizing and arranging your ideas and content in a coherent and logical way. This process parallels the traditional writing process. Thus, while a multimodal text might be considered less “academic” by some students and/or instructors, understanding that all writing and all texts are also multimodal demonstrates that learning about multimodality and how to multimodally compose is just as important as learning how to write.

Why Is Multimodal Composing Important?

You might be wondering why you should multimodally compose in a college writing class. In this section, I provide some answers to this question. I explain how multimodal composing assignments help students practice digital literacy skills, offer an opportunity to transfer multimodal composing experiences from home to academic settings, and allow students to learn “real life” composing practices.

Multimodal Assignments Help You Learn Digital Literacy Skills

You have likely been taught that to succeed in the world, you need to become a literate citizen. The common understanding of “literate” or “literacy” is an ability to read and write alphabetic texts. While it is important to have these skills, this definition privileges words and language over the other modes of communication. It also does not allow for assignments that help you practice communicating using multiple literacies, modes of communication, and technologies in various and diverse writing situations.

The New London Group members were some of the first to argue that students should have opportunities to practice and learn multiple literacies in the classroom, while utilizing emerging technologies. This idea continues to be reflected in writing and literacy goals in many first year writing and writing across the curriculum courses. In fact, check out your syllabus; in many colleges and universities there is a goal related to “digital literacy.” The 2000s saw the arrival of “digital literacy skills” added to many first year writing program’s learning outcomes and include understanding how to react to different writing assignments that require composing practices beyond writing a college essay and learning how to use various technologies to appropriately distribute information. Multimodal assignments offer opportunities for instructors to help you learn these digital literacy skills.

Multimodal Assignments Allow You to Use What You Know

You are likely already sharing and creating multimodal texts online and communicating with a wide range of audiences through social media, which Ryan P. Shepherd argues, requires multimodality. However, in his 2018 study, Shepherd also points out that students struggle to perceive the connections between the digital and multimodal composing they do outside of school with the same types of assignments they are asked to complete in school. What does this mean? Well, it means you are probably already multimodally composing outside of school but you just didn’t know it. Understanding that you are already composing multimodally in many digital spaces will help you transfer that knowledge and experience into your academic assignments. This understanding might also help alleviate any fears or anxiety you may have when confronted with an assignment that disrupts what you think writing should look like. You can take a deep breath and remember that practicing multimodal composing in school connects to the multimodal composing you likely practice outside of school.

Multimodal Assignments Offer Real Skills for the Workforce

Perhaps the most significant reason for learning how to compose multimodally is that it provides “real-life” skills that can help prepare students for careers. The United States continues to experience a “digital age” where employees are expected to have an understanding of how to use technology and communicate in various ways for various purposes. Takayoshi and Selfe argue that “[w]hatever profession students hope to enter in the 21st century . . . they can expect to read and be asked to help compose multimodal texts of various kinds . . .” (3). Additionally, professionals are also using the benefits of digital tools and multimodal composing to promote themselves, their interests, research, or all three. Learning how to create a multimodal text will prepare you for the workforce by allowing you to embrace the skills you already have and learn how to target specific audiences for specific reasons using various modes of communication.

How Do I Create a Multimodal Text?

Now that you know what a multimodal text is and why it is important to learn how to create them, it makes sense to discuss strategies for composing a multimodal text. As with writing, multimodal composing is a process and should not only emphasize the final result. Therefore, the first three strategies listed below are pre-drafting activities.

- Determine your rhetorical situation.

- Review and analyze other multimodal texts.

- Gather content, media, and tools.

- Cite and attribute information appropriately.

- Begin drafting your text.

While I often ask my students to attend to each strategy in the order given, your process might change based on the assignment and/or instructor expectations.

Determine Your Rhetorical Situation

When brainstorming your rhetorical situation, you should consider the purpose of your text (the message), who you want to read and interact with your text (the audience), your relationship to the message and audience (the author), the type of text you want to create (the genre), and where you want to distribute it (the medium). Descriptions of each of the five components of the rhetorical situation are offered below.

The Message

The message relates to your purpose, and you might ask yourself, what am I trying to accomplish? You should try to make the message as clear and specific as possible. Let’s say you want to create a website focused on donating to charity. An unclear message might be “getting more people in the United States to donate to charities.” A clearer message is “convincing college freshmen at my university to donate to the ASPCA” because the audience and purpose are specific rather than broad.

The Audience

There are two types of audiences. An intended audience, who you target in your message, and an unintentional audience, who may stumble upon your text. When determining your message, you want to consider the beliefs, values, and demographics of your intended audience as well as the likelihood that unintentional audiences will interact with your text. Using the example above, college freshmen at your university are the intended audience, and teachers, parents, and/or students from other universities represent unintentional audience members. It might be helpful to approach audience using the concept of “discourse communities,” or “a group of people, members of a community, who share a common interest and who use the same language, or discourse, as they talk and write about that interest” (National Council of Teachers of English). You can read more about discourse communities in Dan Melzer’s essay, “You’ll Never Write Alone Again: Understanding Discourse Communities” found in this volume of Writing Spaces.

The Author

You are the author and should consider your relationship to the message and audience. As an author, you bring explicit (obvious) and/or implicit (not obvious) biases to your message, so it is important to recognize how these might affect it and your audience. Also, you may be targeting an audience you are familiar with (perhaps you are also a college freshman) or not (perhaps you are a graduate student). It is important to think about how your familiarity might affect your message.

The Genre

Genre is a tricky term and can mean different things to different scholars, teachers, and students (Dirk 250). In the context of multimodal composing, genre refers to a type of text that has genre conventions, or audience expectations. For example, if I am creating a website (the genre), an audience would expect the following conventions: an easy-to-navigate toolbar, functional tabs, hyperlinks, and images. Yet, when thinking about genre, it is more useful to think specifically. If I am creating a website for horror film fans (the specific genre), then the audience would expect the following (more specific) genre conventions: references, images, and sounds associated with horror films, directors, actors, actresses, monsters, and villains. They would also expect color and font choices to align with the genre—it is likely that the color baby blue would not be well-received.

The Medium

While genre is the type of text you want to create, the medium refers to where you will distribute it. Classic media (plural for medium) includes distribution via radio, newspapers, magazines, and television; however, new media is defined by a text’s online distribution. Importantly, medium refers to where you will distribute your text but not how. The how refers to the technology tools you’ll use to create the text and possibly to distribute it. For example, to create a podcast, you might use your smartphone (a tool) to record, a free sound editor like Audacity (another tool) to edit it, and Soundcloud (a tool and the medium) to distribute it.

Review and Analyze Other Multimodal Texts

Now that you have brainstormed your rhetorical situation and determined the type of text you want to create, it is time to begin finding other texts representative of your topic and genre. In their textbook, Writer/Designer: A Guide to Making Multimodal Projects, Arola, Sheppard, and Ball argue that “[o]ne of the best ways to begin thinking about a multimodal project is to see what has already been said about a topic you are interested in . . . as well as how other authors have designed their texts on that topic . . . ” (40). This is excellent advice. I suggest that you find at least one text you think is an exceptional example and one text you feel is lacking in some way. After you find these texts, you can conduct a brief analysis by responding to the following questions:

- What is the author’s message?

- Who are they addressing? How can you tell?

- What type of text did they create? What genre conventions do you see?

- How was the text distributed? In what ways does it relate to the target audience?

- What modes of communication are they using? Which are they emphasizing? Do these decisions support the message and/or appropriately target their audience?

- What do you like about the multimodal text?

- What, in your opinion, needs work?

If you answer these questions, you have given yourself important feedback to consider for your own work.

Gather Content, Media, and Tools

Once you have determined your rhetorical situation and examined other multimodal texts, you should begin gathering information and materials. I have categorized this process into three components: content, visual and aural materials, and technology tools.

Conduct Content Research

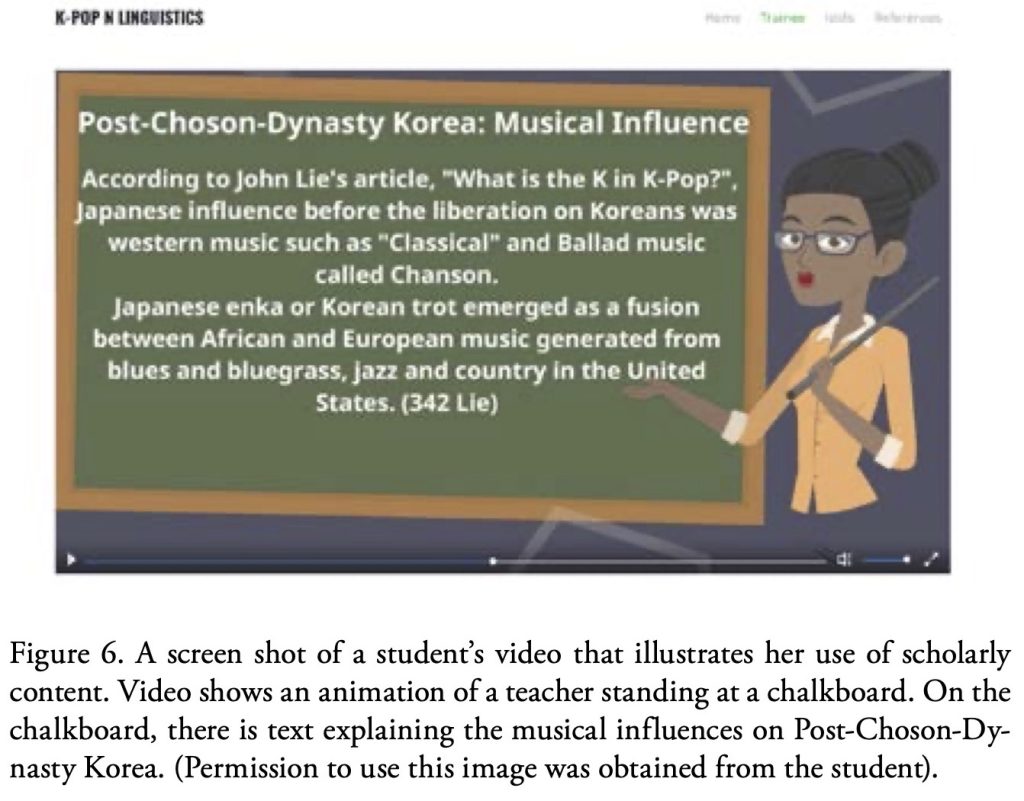

A multimodal text should include content (key pieces of information that support your message), which means you will need to conduct some research. The extent of the research depends on the type of assignment; some instructors might want your multimodal text to include scholarly research while others might not. Therefore, be sure to read the assignment closely and then conduct the necessary research. For example, my student created a website and videos discussing the similarities between American music and K-pop (see figure 6). Her content research includes a scholarly article from the journal World Englishes and a popular article from Billboard.com.

Collect Visual and Aural Materials

In addition to textual information, you should also collect images, sounds, videos, animations, memes, etc. you want to include in your multimodal text. For instance, figure 6 demonstrates some of the pre-draft materials my student collected: openly licensed images of a teacher and chalkboard, a video they created using Animator, and K-Pop music to play on a loop.

Explore Openly Licensed Materials

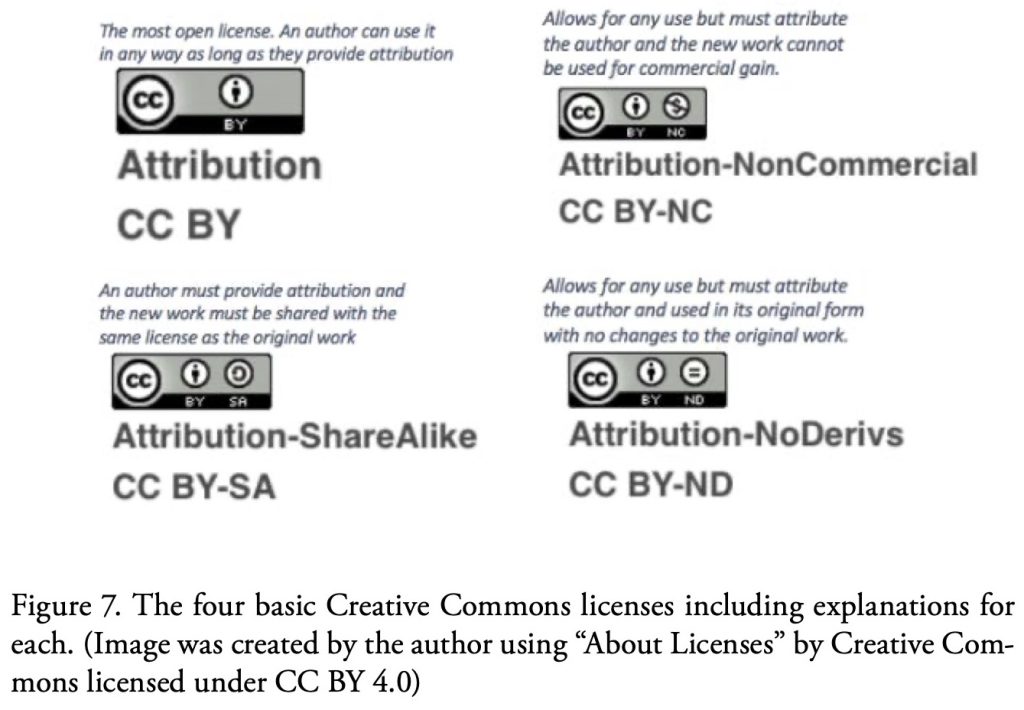

When searching for visual and aural materials, you want to consider using openly licensed materials. According to Yearofopen.org, open licenses are “a set of conditions applied to an original work that grant permission for anyone to make use of that work as long as they follow the conditions of the license” (“What are Open Licenses”). A well-known and commonly used example of an open license are Creative Commons licenses, identified by CC. Creative Commons licenses provide the creator or author with a copyright, ensuring that they receive credit for their work, while also allowing “others to copy, distribute, and make uses of their work – at least non-commercially” (“About the Licenses”). Essentially, if a work has one of the four basic creative commons licenses (see figure 7), then a creator/author can use the licensed item in their own creative texts.

There are various websites such as CC Search, Free Music Archive (FMA), or Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) where you can find openly licensed work. You may also set filters on Flickr or Google Images to locate openly licensed work.

Collect and Evaluate Technology Tools

It is important to collect and evaluate the technology tools you need to create your multimodal text prior to drafting it. As stated previously, the technology tool helps you create the final text and might also help you distribute it. The easiest way to determine the technology tools that you need is to create a list of all of the features you want to include in your text. Once you create the list, research where to find the tools either online or at your university. Be aware that some tools may not be free (although they may come with a free trial period), but you can use software available on your computer or university computers such as iMovie or Windows Movie Maker. Or you can find freeware, software available for free online, such as Audacity (for sound editing), Canva (for infographic and/or image creation), or Blender (for video creation). Once you have created your list and found some tools, spend some time testing each one while keeping track of which is the most user-friendly and helps you achieve your composing goals.

Citing and Attributing Your Content

After researching content and collecting materials, think about how you will give rhetorically appropriate credit to authors or organizations whose work you have referenced or included. For instance, if you create a video, you should provide credits at the end rather than a Works Cited page, or if you design a website, you should include hyperlinks to outside sources rather than MLA in-text citations because this makes more sense, given the genre. For multimodal texts that rely on the aural mode (e.g. podcasts), you can use verbal attributions, or verbalize necessary information. When deciding what information is necessary, think about what you can include to help your audience locate your text, such as author, title, and website. For example, the phrase, “According to Mandi Goodsett, in her PowerPoint ‘Creative Commons Licenses’ found on the library website, a student has con- trol over their online presence,” offers the audience key information to help them find the source.

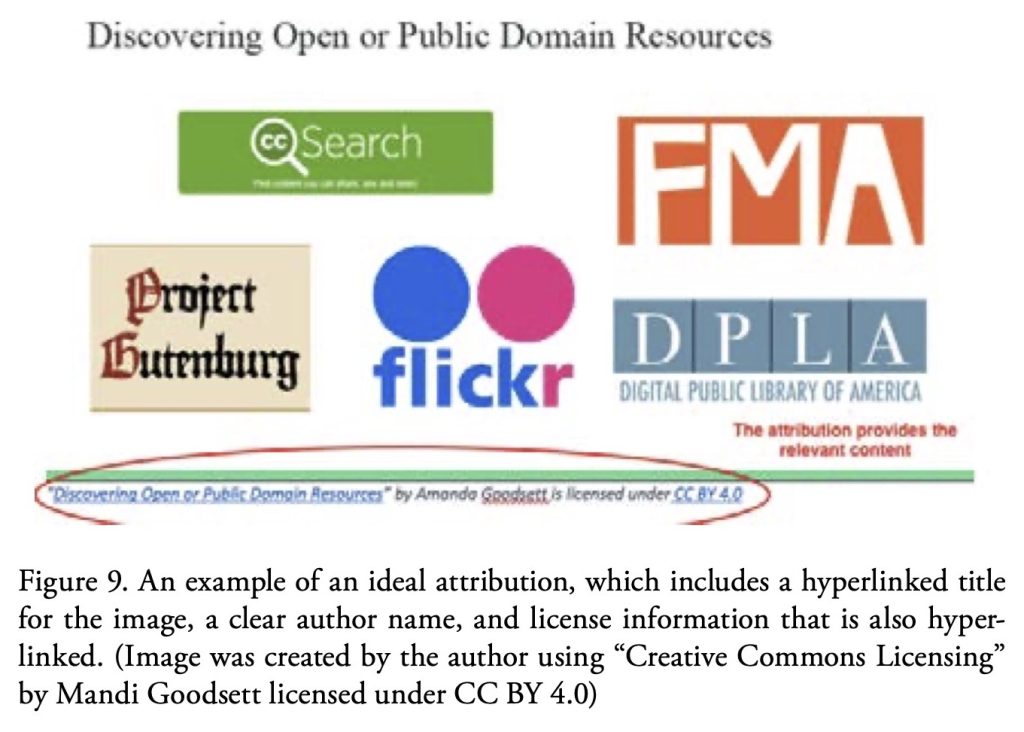

When citing openly licensed images, videos, sounds, animations, screenshots, etc., it is important to provide an attribution. According to the CC Wiki, an appropriate attribution should include the title, author, source (hyperlinked to the original website), and license (hyperlinked to the license information). Figure 8 represents example of an inappropriate attribution and figure 9 an ideal one.

Begin Drafting Your Text

Drafting your text should include outlining or mapping your project. This could take the form of writing all of the text you want to include in an outline if you have a word-heavy multimodal text like a website, drawing your design if you are creating a poster or commercial, or writing a script if you are creating a podcast or video. Of course, you can combine any of these outlining methods or come up with your own, but thinking about what you want to do before you do it will make your final text much stronger and coherent.

Final Remarks and Finding More Information

The primary purpose of this chapter is to introduce you to multimodal composing and offer some strategies to help you create a multimodal text. Yet, just like with traditional writing, multimodal composing is a process, and while I provided three pre-drafting strategies, I did not offer much in the way of guidance for drafting your final product. Therefore, I would like to conclude by offering two excellent resources:

- Michael J. Klein and Kristi L. Shackelford’s Writing Spaces volume 2 chapter, “Beyond Black on White: Document Design and Formatting in the Writing Classroom” discusses visual design, which can help you create your final text.

- Arola, Sheppard, and Ball’s commercial textbook, Writer/Designer: A Guide to Making Multimodal Projects (first and second editions) offers detailed advice for making your multimodal text.

Works Cited

“About the Licenses.” Creativecommons.org, https://creativecommons.org/licens- es/. Accessed 29 May 2019.

Arola, Kristin L., Jennifer Sheppard, and Cheryl E. Ball. Writer/Designer: A Guide to Making Multimodal Projects. Bedford/St. Martin, 2014.

Ball, Cheryl E. and Colin Charlton. “All Writing is Multimodal.” Naming What we Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press 2015, pp. 42-43, https:// ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy-iup.klnpa.org/lib/indianauniv-ebooks/ reader.action?docID=3442949&ppg=140.

CC Wiki. “Best practices for attribution.” Wiki.Creativecommons.org, 9 July 2018, https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/Best_practices_for_attribution. Accessed 29 May 2019.

Dirk, Kerry. “Navigating Genres.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, vol. 1, 2010, pp. 249-262, https://writingspaces.org/sites/default/files/dirk–navigat- ing-genres.pdf. Accessed28 May 2019.

Goodsett, Mandi. “Creative Commons Licensing.” Cleveland State University, 2019, Google Slides, https://drive.google.com/ file/d/1qZJVYF7S8TM_o1AkfTH2cYplvT2R83u9/view.

Klein, Michael J. and Kristi L. Shackelford. “Beyond Black on White: Document Design and Formatting in the Writing Classroom.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writings, vol. 2, 2011, pp. 333-349, https://writingspaces.org/sites/default/ files/klein-and-shackelford–beyond-black-on-white.pdf. Accessed 28 May 2019.

Lauer, Claire. “Contending with Terms: ‘Multimodal’ and ‘Multimedia’ in the Academic and Public Spheres.” Multimodal Composition: A Critical Sourcebook, edited by Claire Lutkewitte, Bedford/St.Martin’s, 2014, pp. 22-41.

Melzer, Dan. “You’ll Never Write Alone Again: Understanding Discourse Communities.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writings, vol. 3, 2019.

National Council of Teachers of English. “Discourse Community.” ncte.org, 2012, http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/CCC/0641- sep2012/CCC0641PosterDiscourse.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2019.

Shepherd, Ryan P. “Digital Writing, Multimodality, and Learning Transfer: Crafting Connections between Composition and Online Composing.” Computers and Composition, vol. 28, 2018, pp. 103-114, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2018.03.001.

Takayoshi, Pamela and Cynthia L. Selfe. “Thinking about Multimodality.” Multimodal Composition: Resources for Teachers, edited by Cynthia L. Selfe, Hampton Press, Inc., 2007, pp. 1-12.

The New London Group. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures.” Harvard Educational Review, vol. 66, no.1, 1996, https://eclass.duth.gr/modules/document/file.php/ALEX03242/3.5.%20The%20New%20Lon- don%20Group.pdf. Accessed 28 May 2019.

“What are Open Licenses.” Yearofopen.org, www.yearofopen.org/what-are-open-licenses/. Accessed 28 May 2019.

Keywords

Creative Commons, multimodal, digital and multimodal composing, multimodality, new media, digital literacy

Author Bio

Melanie Gagich earned her PhD in Composition and Applied Linguistics from Indiana University of Pennsylvania in August 2020. Her dissertation, “Exploring FYW Students’ Emotional Responses Towards Multimodal Composing and Online Audience,” earned a pass with distinction. And she has written two articles exploring multimodal composing and digital literacy. She is also a co-author of the open access textbook, A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing (CSU Ohio Faculty Profile).