Working with Sources

25 Worknets and Invention

Jennifer Clary-Lemon; Derek Mueller; and Kate L. Pantelides

Abstract

In “Working with Sources: Worknets and Invention,” from Try This: Research Methods For Writers, by Jennifer Clary-Lemon, Derek Mueller, and Kate Pantelides offer an alternative to annotated bibliographies for identifying appropriate sources for a research project: worknets. Worknets offer an exploded view of a source, inviting deep engagement and familiarity with a source, which can be the starting place for further secondary source research. The article walks writers through the process of developing a worknet, offering four different ways of interacting with a source: first authors identify representative words in the chapter during the “semantic phase,” then they look closely at the sources that the work draws on during the “bibliographic phase,” next they consider the author’s network during the “affinity phase,” and finally, they identify concurrent events that coincide with the development of the source during the “choric phase.”

This reading is available below and as a PDF.

- It recognizes the history of how sources build on each other by relating new research to past research (homage; timeliness of current research).

- It lends credibility to the author—you!—who, by referencing sources, demonstrates care, ethics, rigor, and knowledge (authority; credibility).

- It revisits claims, data, and key concepts that serve as a foundation to the new research (build-up).

- It positions new research in relationship to the research gaps that it highlights (differentiation).

It’s not enough, in working with a topic—say, climate change—to simply know it is of interest to a variety of scholars. A writer needs to become familiar with the key terms used by the scholarly community working on climate research, such as greenhouse gas and carbon threshold, and the historic data that is fundamental to that research. This might be represented by, for example, how the measurements of carbon levels in the atmosphere that have been taken by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration at the Moana Loa Observatory since 1958 led to noticing that we have surpassed the 400 PPM, or parts per million, carbon threshold that is key to human thinking about climate change. Learning these things allows you to write your way into a complex topic and shows that you know enough to join the conversation.

But how do you begin? This chapter helps you begin to invent ideas by engaging deeply with sources. Seeking and finding appropriate sources and knowing them well enough to incorporate them into your writing is slow work. It can be especially slowed down when you are at the beginning, finding your way into an unfamiliar conversation for the first time. It takes time to trace even a sample of the relations that reach through and across sources.

In this chapter, we focus on one way that you can work with a text, or source, through working with the webs of relationships that extend out from it, or its web of connections with other sources. We call this kind of working with multiple texts sourcework, and it can show itself in a variety of ways—often through library research, keyword searches, paging through a source’s bibliography or Works Cited page, or following a trail of online links or even a hunch about a key idea. Yet sourcework takes time, and that’s something many student writers don’t have a lot of when they are trying to navigate a complex topic and key details of a nuanced argument—all from one source! Given the time it takes to work with sources effectively, here we introduce you to a method of sourcework that we call worknets, a four-part model of working your way through one source such that it leads you towards other sources and ideas that will be useful to the thinking and framing of your project.

The Power of Worknets

Worknets give us a visual model for understanding how sources interrelate, how key words and ideas become attached to certain people, and why provenance—when something was written and where it came from—matters. At the center of any worknet is the source that you or your instructor sees as focal to the conversations happening in your research. Radiating outward from that source, as spokes from a wheel, are what we call nodal connections. Each nodal connection gives you another research path to follow and another way to connect with your source more deeply and less superficially. Often students are called upon to “incorporate five or seven or x sources” as though this is a quick and easy task—it isn’t! But when you can treat a central source as one that leads you in a series of directions, each with its own path toward another source, concept, person, or event, you are more likely to read the whole thing. This will help you understand sources more fully, investigate what you don’t understand, and more easily locate another source. It will also help you gather sources together and see how they connect to each other and what gaps in the sources emerge, which helps you piece together a literature review with your research question front and center.

Worknets provide you with a method for working within and across academic sources. As a way of helping you “invent” what you have to say, worknets are a source-based way of helping you to generate a path for your research that points you toward a particular question, gap, or needed extension of what has come before. A finished worknet consists of four phases: a semantic phase, which looks at significant words and phrases repeated in the text; a bibliographic phase, which connects your central or focal source to the other works the author has cited in her piece; an affinity phase, which shows how personal relationships shape sourcework; and a choric phase, which allows researchers to freely associate historic and sociocultural connections to the central source text.* After developing a finished worknet, which involves all four phases placed visually together, you will have many openings for further research, and you will have gained a handle on the central source such that incorporating it into your writing via direct quotation, paraphrase, or summary is easier for you to achieve and more interesting for an audience to read. Worknets can follow the proposal you developed in Chapter 1, or they can offer you a method for reading sources that supports your drafting and refining a research focus and related proposal.

* In terms of delivery, a complete worknet project can stand alone, it can serve as a useful building block for an annotation that is part of a larger annotated bibliography, or it can function as a starting point for a literature review.

Try This: Summarizing a Central Source (1 hour)

Return to the research proposal that you generated in Chapter 1 or “Making an Argument for Your Research” in Chapter 2. Spend some time coming up with key terms or phrases that succinctly capture your research interests, practicing with Boolean operators such as and, or, and not (e.g., “trees and diseases and campus”; “texting or IM and depression”; “composition and grades not music”). Begin with your library’s databases in your major and, using these key terms, start narrowing your search to academic articles (rather than reviews, newspaper articles, or web pages, for example) using these key terms. Skim at least five sources as you look for your central source, taking notes on the following:

- What is the purpose of the research article?

- What methods did the researchers use to answer their research question?

- What did the researchers find out?

- What is the significance of the research?

- What research still needs to be done?

Taking these notes will allow you to see if the source you’ve read really connects with your curiosities and research direction. They also clearly lay out the basis of most academic articles: a hypothesis (the research question), methods (the tools used to answer a research question), results (what you found out), and discussion (why it matters). Putting these together in 50-100 words allows you to generate a summary of the key points of an academic article, letting you select the article that is the most interesting and central to your research question to begin your worknets.

To develop a worknet, begin by selecting a researched academic article published since 1980.* This date may seem arbitrary, but we consider it a turning point because major citation systems shifted in the 1980s from numbered annotations to alphabetically ordered lists of references or works cited. As you read the article you select, you will, in four distinct but complementary ways, focus on a different dimension of the source’s web of meaning, one at a time. Worknets typically pair a visual model and a written account that discusses the elements featured in the visual model. For the guiding examples that follow, we have developed visual diagrams using Dana Driscoll’s “Introduction to Primary Research: Observations, Surveys, and Interviews,” published in 2011. Driscoll explains in her article the differences between primary and secondary research, details types of qualitative research methods, and provides student examples of research projects to help readers conceptualize her advice about conducting primary research. Because her article ties so closely to what this book is about—research methods—we’ve selected it as a central source to model the worknets process.

* Keywords are increasingly important as part of knowledge-making. In published academic articles, keywords are tracked and collected so that we can easily find them through online database searches, telling us what central idea an article is forwarding.

Phase 1: Semantic Worknet—What Do Words Mean?

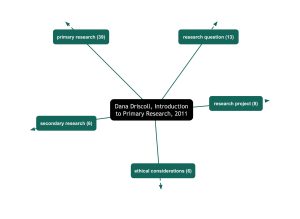

When creating a semantic worknet (Figure 3.1), you pay attention to words and phrases that are repeated throughout the central source (“semantics” is the study of meaning in words). Because academic writers repeat and return to concepts that they want readers to remember, by repetition we begin to understand the idea of a keyword or keyphrase*—those words and phrases that are doing the work of advancing a source’s central ideas. By noticing these key words and phrases, we understand first where they come from and how they have been initiated and second how they are being used to create a common understanding between members of a particular academic discipline, community, or group of specialists. Although such keywords and phrases can at first seem inaccessible, strange, or confusing, noticing them and investigating their meaning is a sure way to begin grasping what the article is about, what knowledge it advances, and the audiences and purposes it aspires to reach.

There are several different ways to come up with a list of keywords and phrases. One approach is to manually circle or underline words and phrases as you read, noting them as they appear and reappear in the text so you can return to them later. Other approaches make use of free online tools, such as TagCrowd (tagcrowd.com/), where you can copy and paste the text of the article and initiate a computer-assisted process that will yield a concordance, or a list of words and the number of times they appear in the text. NGram Analyzer (guidetodatamining.com/ngramAnalyzer/) is another effective tool for processing a text into a list of its one-, two-, and three-word phrases. Across multiple sources, beginning to find words and phrases that match up will help you locate key concepts for the literature review section of your research project.

A semantic worknet also helps you understand specialized vocabulary on your own terms, acting as a gateway into the terminology in the article. Noticing these words and phrases is a first step toward learning what the words and phrases mean. In Figure 3.1, you will see arrows extending outward from each term, radiating toward the edge of the image. This minor detail is a crucial feature of the worknet. It says that there is more, a deeper expanse beyond this article. That is, it suggests the generative reach of the words and phrases stemming from the article. Clearly an echo of the title, the phrase “primary research” appears in Driscoll’s article 39 times, three times more than the next phrase, “research question,” at 13. The article differentiates primary and secondary research. These keywords and phrases remind us of this. But the article also repeats the phrase “research project” and “ethical considerations.” Each of these repeated keywords and phrases are included in the worknet.

Try This: Finding Keywords (30 minutes)

You’ve chosen an article you consider to be interesting and relevant to your emerging research question. In anticipation of developing the semantic phase, spend time analyzing the article by doing the following:

- Read through the article, noting the title and any headings. Make a list of words that you find central to the text.

- Does the article provide a list of keywords at the beginning? If so, do any of them surprise you or differ from what you would have selected? Which ones overlap with the ones you compiled during your reading?

- Choose some of the keywords you’ve identified from the list supplied by the article or from the list you have generated. Next, without looking up any of the terms in the article or in any dictionary, attempt to write brief definitions of these terms. What does each keyword mean? Note with a star those terms you believe to be highly specialized.

After creating your worknet, we encourage you to create a 300-500 word written accompaniment of the visual worknet, based on the questions in the next “Try This,” that helps you think through the “why” of the source’s keywords and phrases. The notes you take as a part of the semantic worknet will not only give you a greater understanding of the central source you’ve read, but will also link to others in the conversation, giving you a fuller body of sources from which to orient your research proposal or project.

In addition to providing insight into the article, the family of ideas it advances, and the disciplinary orientation of the inquiry, noticing keywords and phrases can also inform further research, providing search terms relevant for exploring and locating related sources. It can lead you toward examining why an article covers some things with more repetition (in Driscoll’s example, ethics), but not others (for example, finances and how they relate to ethical choices). When gaps appear between what a source says and does not say, those gaps are interesting places to orient your own research question.

Try This: Developing your Semantic Worknet (1-2 hours)

Select three to five keywords and develop the visual model demonstrated in Figure 3.1. After adding the appropriate nodes to the diagram, in 300-500 words, develop a critical reflection on your selected visual semantic worknet, using the following questions to guide you:

- What does each word or phrase mean, generally? What do they mean in the context of this specific article?

- Does the author provide definitions of the terms? More than one definition for each term? Are there examples in the article that illustrate more richly what the words or phrases do, how they work, or what they look like?

- Who uses these phrases, other than the author? For example, who are the people in the world who already know what “primary research” refers to? What kind of work do they do? Why?

Phase 2: Bibliographic Worknet—How do Sources Intersect and Draw from Each Other?

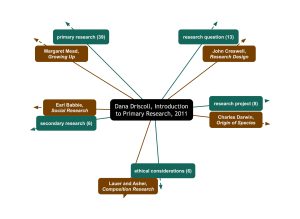

In the second phase of working with your central article, we ask you to investigate its bibliography*—the list of sources that the author of your article has paraphrased, quoted, and summarized—by selecting, finding, and skimming or reading sources from the bibliography. (Bibliographies are located at the end of research articles; they may be titled “Works Cited,” “References,” or “Bibliography,” depending on the documentation style.) You can choose any source that is found in the back matter, footnotes, or endnotes of your focal article to work with, and we recommend beginning with five or so. You might select the most significant sources—the ones that the author cited most frequently or drew from extensively—or you might simply select the ones that are most interesting to you. Either approach will be useful—they’ll just yield different results. Attention to a source’s bibliography is a way to begin tracing how sources use other sources to make their arguments. When we pay close attention to bibliographic references, we begin to see the links we might make 1) between keywords and phrases and a bibliography or Works Cited page and 2) between a central author and the sources with which they work. We begin to see that ideas don’t just happen—they are connected to ideas that came before them. This foregrounds the interconnection of the article’s main ideas and sources it draws upon, shedding light on the many ways in which academic research builds upon precedents by extending, challenging, and reengaging historical texts.

* To notice a source in a bibliography and then to retrieve it and to read it can bloom into a research trajectory before unforeseen.

Developing a bibliographic worknet like the one in Figure 3.2 calls attention to choices the author has made to invoke specific writers and researchers and their work in the article. It tells of a deeper and thicker entanglement, a web whose filaments extend beyond the obvious references into work that has gone before, sometimes recently, sometimes long before. By involving sources in the article, the author orients what are oftentimes central ideas while also associating those ideas (via the sources) with tangible, identifiable, and (sometimes) accessible precedents. This step is like the development of an annotated bibliography, or a list of sources relevant to a research project that include brief notes about the significance of a source to a wider conversation. An annotated bibliography provides an invaluable intermediate step toward developing a literature review.

In a journal article, the sources an author cites are listed at the end of the article. Their position implies secondary relevance. And yet the references list is an invaluable resource for further tracing and for discovering, by following specific references back into the article, just how unevenly the sources become involved in the article. That is, a references list makes sources appear flat and equal, but among the sources listed, it is common to find that only a quarter of them (or even less, sometimes) figure in substantial and sustained ways throughout the article. Many others are light, passing gestures. The bibliographic worknet can help you differentiate between the two and begin to notice which sources loom large and which are but briefly invoked.

Reading along and across the sources cited is akin to following leads and accepting invitations to further inquiry, formulating new or more nuanced research questions, and discovering influences that are intertwined, eclectic, and complementary. Finding a source and reading it alongside your focus article, too, can yield insights into the highly specific and situated ways writers use sources. For example, if you’re researching climate change and just read a paraphrase or a brief quote from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration at the Mauna Loa Observatory’s 1958 data, you’ll only have a part of the story. However, if you find that data and read it yourself, you might find that there are different parts of the data that you think are important to highlight. You might have a different perspective on the research, or you might find that you better understand the original article that led you to this text. Either way, your understanding of the original article, the larger research area, and the intersection between the two sources will deepen.

Try This: Developing Your Bibliographic Worknet (1-2 hours)

After adding the appropriate nodes to your diagram (as in Figure 3.2), in 300-500 words, develop a critical reflection on your selected visual bibliographic worknet, using the following questions to guide you:

- Which of these sources are available in the library? Which are available online?

- What is the average age of the sources? What might the date of the sources say about the timeliness of the article? What is the oldest source? Which is most recent?

- Are there sources that are inaccessible or out of circulation? How did the author locate such sources in the first place?

- How did the focus article use or incorporate the source materials? Were they glossed or briefly mentioned? Were large parts summarized into thin paraphrases? Were the whole of the works mentioned or just key ideas?

- Which of the sources, judging by its title, is most likely to cite other sources in the list? Which is least likely?

Try This: Developing a Rapid Prototype (30 minutes)

Before we go farther, let’s pause and try this out. Notice that the first two phases of developing a worknet are concerned with things you will find in the source—keywords and phrases and sources cited. Work with any text you choose (an assigned reading for this class or another class or a source you can access quickly) to develop a rapid prototype, a swiftly hand-sketched radial diagram focusing only on the first two phases. You could share the diagram with someone who has read the same source and compare your radiating terms and citations. You could write about one or two of the terms or citations to anticipate their relevance to your emerging project. Or you could write about (or discuss) what the presence or absence of selected terms or sources says about the source you’ve chosen.

And/Or, Try This: Investigating Lists of Sources (1 hour)

Works cited or references lists may appear to be simple and flat add-ons at the end of an article or book, but we regard them to be rich resources for thinking carefully about a writer’s choices. Look again at the works cited or references list for your chosen article, this time with an interest in coding and sorting it. This means you will look at the references list with the following questions to guide you:

- How recent are the sources in the list? Plot them onto a timeline to indicate the year of publication from oldest to newest. Which decade do most of the resources come from?

- How many of the sources are single-authored? How many are co-authored? How many are authored by organizations, companies, or other non-human entities (i.e., not by named human authors)?

- How many of the sources come from books? How many from journals? How many are available only online? How many are published open access?

- Ethical citation practices include awareness of the kind of voices represented through the works you’ve consulted. Given that you can only know so much about an author through a quick Google search, consider what voices are included. Which voices are amplified, and which are missing altogether? You might consider developing a coding pattern to highlight the ways in which the authors represented identify in regard to gender, race, and ethnicity. Such an effort is fraught, yet it can begin to highlight patterns important for readers of sources to understand who is and is not being cited.

Among these patterns, which are significant for understanding the article, its authorship, or the contexts from which it was developed? What can you tell about the discipline or about the citation system based on coding the works cited or references list as you have?

To create a bibliographic worknet, begin by reading the references list, footnotes, and endnotes and highlighting the sources that pique your curiosity. Once you’ve sampled from the list, take your sources to your library database to see what you can find. Try to locate three to five other sources from the bibliography, noting to yourself how difficult or easy these sources were to find. Once you’ve located your bibliographic sources, take a look at the pages that your central source cited and how the ideas on those pages were used in the focal source. Put the borrowed idea in context and try to figure out how and why your central source chose the bibliographic source to work with. Sampling from a bibliography, whether purposeful or random, can lead to promising new questions and promising new sources that can inform, guide, and shape your research questions. When you compose a 300-500 word written accompaniment of the bibliographic worknet, it is in service to thinking through where sources come from, how history marks sourcework, how findable sources really are, and how authors use other sources to create their key arguments.*

* Believe it or not, a references list is a gift from an author to a reader and an invitation to follow paths of inquiry that are already well begun and often many years in motion.

By the time you’ve collected three to five sources for your bibliographic worknet and noted some emergent key terms from your semantic worknet, you will be in good shape to begin to chart the major ideas, patterns, and distinctions among a group of sources. This will help you determine which sources hang together with a kind of “idea glue” that may help you, as a researcher, figure out which sources best frame your research question and which sources are less important in framing your research direction—this is how literature reviews begin to develop.

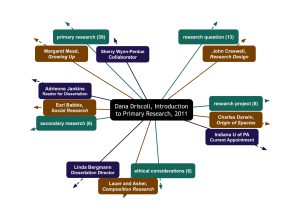

Phase 3: Affinity Worknet—How Are Writers Connected?

In the third worknet phase, you pay attention to ties, connections, and relationships—affinities—between the central article’s author and others in the research field you are exploring. An affinity worknet takes into account where the author has worked, what sorts of other projects she has taken up, and whom she has learned from, worked alongside, mentored, and taught. Many other authors are continuing research related to the article you have read. They are also keeping the company of people who do related work, whose research may complement or add perspective to the issues addressed in the article. You can see these relationships illustrated in the affinity worknet for our sample article in Figure 3.3.

* For example, if you research the three authors of this text, you’ll find that they have all co-authored other projects together, worked at the same institutions at times, and collaborated on research presentations.

Try This Together: Where Can I Find Affinities? (30 minutes)

Among the central premises in the affinity phase is that we can learn something about a writing researcher by noticing the company they keep. That is, by looking into professional and social relationships that have operated in their lives, we can begin to understand the larger systems of which their ideas—and their research commitments—are a part.

To treat this as its own research question would be to ask the following: What kinds of relationships can we learn about and by what means can we learn about them? Certainly simple Google searches may provide a start, but where else might you look? Work with a partner to generate a list of possible leads—platforms or social media venues where you might check to find out more about the lead author of the article you’ve chosen to work with.

Where can you find information about an author’s affinities? A Google search for the author’s name may lead you to an updated and readily available curriculum vitae, which is like an academic resume. Such a search might also lead to the author’s social media activity (Facebook or Twitter accounts) or to a professional web site that provides additional details about collaborations and relationships. For perspective on intellectual genealogy related to a doctoral dissertation, you can turn to your library’s database resources page and look into ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, which indexes information about major graduate projects and the people who participated on related committees. This lead can yield insight not only into who the author is and how she is connected to others but also into where an author’s work comes from in the earliest stages of her career. You’ll finish the affinity worknet having both a larger repertoire of research strategies and a wealth of people and places to lead you to other sources that you might not have otherwise thought of.*

* In fact, if you consider their overlapping affinity networks, you might more easily understand how this book came to be, how their collaborations and individual projects over the last decade or so coalesce in an interest in research methods and, in particular, explicit discussion of such methods with undergraduate students.

Finding these affinities will also help you hone your research skills, allowing you to see that lives and connections can be traced through sources other than traditional library databases.

Try This: Writing about Your Affinity Worknet (1-2 hours)

After adding the appropriate nodes to the diagram (as in Figure 3.3), in 300-500 words, develop a critical reflection on your selected visual affinity worknet, using the following questions to guide you:

- What other kinds of work has this author written? When? For what audiences and purposes?

- Does the article in question bear resemblance to their other research? Does it seem to inform or influence their teaching or other responsibilities?

- Who has the author collaborated with on articles or on grants? What are the research interests and primary disciplines of these collaborators?

- Does the author appear to be active in online conversations? Where, and what do these interactions appear focused on? Are they professional and research-related or more casual and social?

- Where did the author study? With whom? What might be some of the ways these places and people influenced the author?

Phase 4: Choric Worknet—How Is Research Rhetorically Situated in the World?

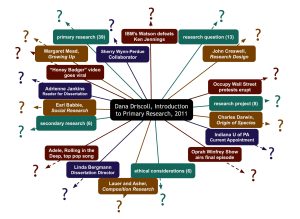

With the fourth phase, worknets grow curioser, adding to the mix what we identify as choric elements. Choric elements take into account the time and place in which the article was produced. Choric worknets gather references to popular culture, world news, or the peculiarities and happenings that coincided with the article’s being published. The term choric comes from the Greek, khôra, the wild, open surrounds as yet-unmapped and outside the town’s street grid and infrastructure. Notice, too, the word’s associations with chorus, or surrounding voices. With this in mind, we regard the choric worknet as exploratory and playful, engaging at the edges so that readers might wander just a bit. Sometimes our best ideas are those that seem, at first glance, to be farfetched.

Compared to the other phases, the choric worknet orbits in wider and weirder circles, drifting into uncharted and therefore potentially inventive linkages. Considering the time and place in which an article was written helps bring us as readers to that time and place. Venturing into the coincidental surrounds can lead to eureka moments, inspiring clicks of insight, curiosity, and possibility, but it can also prove to be too far flung, too peculiar to be useful. This is one of the lessons of research: sometimes we spend time on what we think will be useful, but as any Googler-down-the-rabbit-hole- of-YouTube knows, sometimes what we think will be useful isn’t. Yet it is in the trying that we learn how to weed out as well as how to hold close what is exciting, original, and odd.

This phase encourages you to find those rabbit holes, if only for a moment. Begin with the year your focal article was published, where the author wrote it, and begin an online search, paying attention to what was happening in the world that year. Follow your hunches, your interests, and even the ways that what you’ve found in the other worknet phases maps on to where your meandering is going. Look at Figure 3.4 and you will see five choric nodes. Their selection came from 30 minutes of online searches related to 2011, primarily, and also a few related to Southeast Michigan, Detroit, and Oakland University, the university where Dana Driscoll worked when she wrote the article. Each of the five nodes reflects your choice, something noteworthy or intriguing.

The choices you make in creating the nodes can spark the beginnings of researchable questions and may be reflected in your 300-500 word account of the choric worknet. For example, the node for the “Honey Badger” video going viral as it coincides with Driscoll’s article on primary research methods might instigate research questions concerning just what kind of researched claims the video makes, the relationship of video to writing, and the edge of seriousness and playfulness in composing research that will circulate publicly. This element in the choric worknet, although it at first may seem trivial, can also pique curiosity and invite inquiries into what animals know or into their biology and ecology, such as in the This American Life podcast episode, “Becoming a Badger.” For any student who began reading their focal article with few ideas about their own research path, the choric phase will give you an abundance of options to test and play with the limits and openings of a research project.

Given the messiness of invention—its combinations of purpose and digression, insight and failure, getting lost and then deciding on a direction— the choric worknet stands as the most wide open, potentially the richest of the four phases, even as it risks being the most wasteful, inviting oddball and offbeat ties. Such ties, however, situate the article in the wider world, and they do so while also honoring the place you stand as a researcher, tapping into the interests and curiosities that compel you most.

Try This: Writing about Your Choric Worknet (1-2 hours)

After adding the appropriate nodes to the diagram, in 300-500 words, develop a critical reflection on your selected visual choric worknet, using the following questions to guide you:

- What was happening in the wider world coincident with the time and place of the focal article’s being written and published?

- Why have you selected the assortment of nodes you have? How did you find them? What about them compelled you to add them to the worknet?

- Where do you locate possibilities for further exploration and for emerging interests at the juncture of any choric node and any other node in the radial diagram?

- Which of the choric nodes is most relevant, in your view? Which is least?

- Are there choric nodes you thought about including but later abandoned? What motivated you to make such choices?

Branching Out—Taking Worknets Farther

With the four phases completed, as in Figure 3.5, the worknet introduces initial, inventive branchings, a web of filaments, or trails, that invite further inquiry and that may prime further questions. When experienced researchers read scholarly sources, they usually do so to support, reinforce, or clarify claims they have already begun to formulate. In early stages of research, however, reading scholarly sources oftentimes yields more questions, and these questions each set up further inquiry. Worknets position scholarly sources as resources for invention, and after developing all four phases, you will begin to see that you have many more options for expanding your emerging interests than you initially realized. This approach resonates with the idea of copia,* or lists of possibilities, which suggests that having more than you need to continue research is a wonderful place to be.

* When we write with copious questions—just as worknets provide—we rarely run out of things to say. Allowing for this wandering helps us think more abundantly about what there is to say on a topic, what is still unknown, and how we can follow the research paths that most ignite our passions.

While a single worknet can engage us with new ideas entangled in a web of relationships extending from an article, a series of worknets—that is, worknets applied to two or three or more related articles—can form the foundation for a substantial backdrop to a research project. In fact, a compilation of worknets provides you with the basis of a literature review, that portion of a researched project that provides orientation to established research related to your area of inquiry.

Really Getting to Know Your Sources

Worknets provide a stepwise process to get to know your sources. The better known and better read the sources, the more nuanced and precise will be the literature review that emerges from your work with them. Certainly there are other intermediate note-keeping options and less involved approaches to the phases presented in this chapter. For example, an annotated bibliography might require you to gather and write brief summaries of related sources, focusing on the relevance of the source to your research question. Whether you take up the method we introduce and produce a full, complete worknet for one source, or whether you apply selections of the phases to one or more articles, perhaps adapting by writing annotations or sketching worknets by hand, the approach introduced here will help shape your own work.

Try This: Finding Connections, Near and Far (30 minutes)

The choric nodes are the most likely to introduce variety and surprise. They fan out the article’s web of relations, finding (possible) connections that may hint at new or slightly altered researchable questions. After you develop the choric phase of the worknet for your chosen article, identify both the node you consider to be most related and the node you consider to be least related. Write for five minutes on each node, accounting for why you think it to be more or less related. What do each of these nodes indicate about the world from which the article emerged? What do each of these nodes say about what you find interesting or about your own curiosities in this context?

Modeling Worknets

We have seen students do distinctive, innovative work with worknets, and we’re spotlighting one such example to give you an idea of what is possible. One undergraduate student at Virginia Tech applied all four phases to a 2015 article by Armond Towns, “That Camera Won’t Save You! The Spectacular Consumption of Police Violence.” The article discusses issues related to body cameras, social justice, police violence, and the presumed security bestowed on technological devices. In this case, the worknet followed the steps introduced in this article, culminating in all four phases layered into Figure 3.6.

Additionally, the student was invited to translate the visual and textual worknet into a 3D model, using materials from a local art supply store. The model materialized the worknet as a physical sculpture, conveying more fully an understanding of the article as entangled with the words, sources, relationships, and time-place coincidences of the moment in which it was produced. Figure 3.7 shows the potential of extending the worknet one step farther by creating a model whose dimensions and materials exceed the page or the screen.

Using Worknets to Develop a Literature Review

Although literature reviews serve different purposes from discipline to discipline and vary in scope from one project to another, they have in common the purpose of orienting readers to relevant scholarship. Literature reviews provide a synthesis, or glancing overview, that weaves together relevant focuses and acknowledges limitations, or knowledge gaps, in the series of sources gathered in the review. By the time you’ve finalized a worknet, you will have read and skimmed at least ten sources around a common research theme and question that interests you. Looking again, consider some of the ways specific worknet phases can support your development of a literature review:

- Semantic worknet (phase 1): How are specific keywords and phrases used differently from one source to another? How do different keywords and phrases across a selection of sources suggest yet more refined possibilities for impactful terms not yet introduced in the sources gathered?

- Bibliographic worknet (phase 2): How do the articles you have collected respond to common sources? What can be said about each article’s timeliness based on the ages of the sources it consults?

- Affinity worknet (phase 3): How do connections with other people or institutions reveal the priorities of the authors of your sources? What can you discern about the relationship of each article to an academic discipline?

- Choric worknet (phase 4): What is the relationship of each article to contemporary events? How might those events have influenced its message?

With a series of worknets built from different but related sources, you have carried out a generative, robust method for assembling, annotating, and interweaving sources. Literature reviews require thoughtful balancing of sources, making reference to sources so they are represented concisely and fairly. Worknets, for the practice they give you with moving in and out of texts, support the development of effective literature reviews.

Focus on Delivery: Writing a Literature Review

A literature review is a synthesized grouping of academic sources that have been chosen to frame a larger piece of research and that relate to a research question a writer is pursuing. Some literature reviews are stand-alone pieces to say “this is what’s out there on a particular topic.” Most literature reviews are front matter for larger academic papers. The scope of your project will determine how many sources go into your literature review.

By “literature,” we mean academic scholarship chosen about a certain topic that helps to answer a particular research question. By “review,” we mean a summary of the literature’s argument and an explanation of its connection to the other sources that you use.

To write a literature review, complete these steps:

- Locate five to ten sources that you think would be useful for understanding the research question.

- Skim these sources.

- If the source is relevant to your research question, read it fully and annotate it, writing a 100-word summary of the source in your own words. Read the source’s bibliography to add relevant sources you find there to your working source list.

- Discard irrelevant sources and locate ones that are more specific to your research question. Annotate all relevant sources.

- Read your 100-word summaries and try to figure out how they go together. What are their common features, key words, and theoretical frameworks? What year were they written? Could sources be grouped historically, theoretically, or thematically?

- Use your worknets to help you group your sources in different ways in order to see patterns between and among your sources:

- What similar ideas and words are used to discuss major ideas in your research area among your sources? How do they differ? (semantic)

- What changes when you move your sources into chronological order from earliest to latest or latest to most recent? (bibliographic)

- What happens when you group sources by relationships between and among sources? (affinity)

- Would your review benefit from adding historical and cultural context? (choric)

- Consider how these sources together lead up to your research question. Why is it important, timely, and relevant to previous research?

- Revise your annotations and put them together in such a way that the connections between them are clear and the connections to your research question are visible.

What’s important for you to know about literature reviews is that the choices about what sources to use and what makes them go together are not immediately clear for a reader, which means part of writing a literature review is including that rationale within the review itself. By reading your literature review, your audience should be able to figure out the “idea glue” that holds all of the literature together, inclusive of your project’s purpose and the main conversations taking place within your research area. A reader should walk away from your literature review knowing exactly why you’ve chosen these sources to go together, as opposed to millions of others that could be chosen instead.

Works Cited

Driscoll, Dana L. “Introduction to Primary Research: Observations, Surveys, and Interviews.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, edited by C. Lowe and P. Zemliansky, vol. 2, WritingSpaces.org/Parlor Press/The WAC Clearinghouse, 2011, pp. 153-74. The WAC Clearinghouse, wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/writingspaces2/ driscoll–introduction-to-primary-research.pdf.

Glass, Ira, host. “Becoming a Badger.” This American Life, episode 596, WBEZ, 9 Sept. 2016, www.thisamericanlife.org/596/becoming-a-badger.

Johnson, Alonda. “3D Model of Worknet for Armond Towns’ ‘That Camera Won’t Save You! The Spectacular Consumption of Police Violence.’” 14 Nov. 2018.

ENGL1105: First-year Writing: Introduction to College Composition, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, student work.

Johnson, Alonda. “Worknet of Armond Towns’ ‘That Camera Won’t Save You! The Spectacular Consumption of Police Violence.’” 14 Nov. 2018. ENGL1105: First-year Writing: Introduction to College Composition, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, student work.

Towns, Armond R. “That Camera Won’t Save You! The Spectacular Consumption of Police Violence.” Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society, vol. 5, no. 2, 2015, www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-5/that-camera-wont-save-you-the-spectac-ular-consumption-of-police-violence/.

“Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide.” Carbon Cycle Greenhouse Gases, NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory, 5 Oct. 2021, gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends/.

Keywords

Author Bios

Jennifer Clary-Lemon is Associate Professor of English at the University of Waterloo. She is the author of Planting the Anthropocene: Rhetorics of Natureculture, Cross Border Networks in Writing Studies (with Mueller, Williams, and Phelps), and co-editor of Decolonial Conversations in Posthuman and New Material Rhetorics (with Grant) and Relations, Locations, Positions: Composition Theory for Writing Teachers (with Vandenberg and Hum). Her research interests include rhetorics of the environment, theories of affect, writing and location, material rhetorics, critical discourse studies, and research methodologies. Her work has been published in Rhetoric Review, Discourse and Society, The American Review of Canadian Studies, Composition Forum, Oral History Forum d’histoire orale, enculturation, and College Composition and Communication.

Derek N. Mueller is Professor of Rhetoric and Writing and Director of the University Writing Program at Virginia Tech. His teaching and research attends to the interplay among writing, rhetorics, and technologies. Mueller regularly teaches courses in visual rhetorics, writing pedagogy, first-year writing, and digital media. He continues to be motivated professionally and intellectually by questions concerning digital writing platforms, networked writing practices, theories of composing, and discipliniographies or field narratives related to writing studies/rhetoric and composition. Along with Andrea Williams, Louise Wetherbee Phelps, and Jen Clary-Lemon, he is co-author of Cross-Border Networks in Writing Studies (Inkshed/Parlor, 2017). His 2018 monograph, Network Sense: Methods for Visualizing a Discipline (in the WAC Clearinghouse #writing series) argues for thin and distant approaches to discerning disciplinary patterns. His other work has been published in College Composition and Communication, Kairos, Enculturation, Present Tense, Computers and Composition, Composition Forum, and JAC.

Kate Lisbeth Pantelides is Associate Professor of English and Director of General Education English at Middle Tennessee State University. Kate’s research examines workplace documents to better understand how to improve written and professional processes, particularly as they relate to equity and inclusion. In the context of teaching, Kate applies this approach to iterative methods of teaching writing to students and teachers, which informs her recent co-authored project, A Theory of Public Higher Education (with Blum, Fernandez, Imad, Korstange, and Laird). Her work has been recognized in The Best of Independent Rhetoric and Composition Journals and circulates in venues such as College Composition and Communication, Composition Studies, Computers and Composition, Inside Higher Ed, Journal of Technical and Professional Writing, and Review of Communication.

Attributions

This chapter, “Working with Sources: Worknets and Invention,” by Jennifer Clary-Lemon, Derek Mueller, and Kate Pantelides is from Try This: Research Methods for Writers licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.

the assumption that there is one clear answer to a

research question

a group of people who share a common concern, a set of problems, or an interest in a topic and who come together to fulfill both individual and group goals

an understanding of research that considers the interactions between researchers, research subjects, and their environments

existing in the mind; belonging to the thinking subject rather than to the object of thought

refers to the reputation or believability of a speaker/rhetor; ethical appeals tap into the values or ideologies that the audience holds (audience values) or appeals that lean on the reputation or believability of the speaker/author (authorial credibility)

the finding out or selection of topics to be treated, or arguments to be used; often referred to as the brainstorming or prewriting stage of the writing process, though invention takes place across the writing process

how the compositions we develop reach the audience; in classical Greco-Roman rhetorical tradition, it was primarily concerned with speakers who in real-time stood before reasonably attentive audiences to speak persuasively about matters of civic concern; in modern tradition it is associated with genre, medium, circulation, and ecologies

a phase in research where you will be attentive to keywords in the text you’ve selected

the phase in research where you will trace

intersections between sources

the phase of research where you will consider how writers are connected to each other

the phase of research where you will consider the broader rhetorical

context in which an article is written

the ways in which genres are circulated (or not); can be a measure of a genre’s success with an audience

research that has been considered and shared by

a community of experts

the relationship between texts, especially literary ones; a concept that describes how

other people’s language is seamlessly embedded in our own

treatment in accordance with the rules or standards for right conduct or practice, especially the standards of a profession

nearness in space, time, or relationship

Beneficence asks

whether the research is charitable,

equitable, and fair to

participants by taking

into full account the

possible consequences for the researcher

and the participants.

your plan for research

the particular way you will describe your research to participants