Reflection

49 What’s the Diff? Version History and Revision Reflections

Benjamin Miller

Abstract

Introduction

Whether you know it or not, you revise as you write. Even if you produce a first draft and never come back to it, something tells me you at least look back at the sentence you’re in the middle of, and sometimes the sentences and paragraphs before that, so you know whether your current thought actually follows on the previous one. Or maybe one of your teachers made a point of telling you to write a rough draft, put the paper away for a while, and come back to it; in that case, you’re probably even more aware of revising. But I’ll also bet that even within each of those sessions, you were in the middle of saying one thing and thought of a better idea, or a better way of saying it—so you erased, you went back to the middle or beginning of the line, and you restructured it. The writing led to a better understanding, which led you to change what you were writing. And that’s revision. In this essay, I want to help you understand revision better. I want to help you think through what you do with words and sentences, because what we do within sentences we can also do with paragraphs, pages, and even larger chunks of writing. Studies have shown that expert writers revise on those large scales more than beginners do, so learning to think big is part of how we grow our expertise as writers. And the tool I recommend for seeing revision better is version history. You may know it better as track changes, or (if you’re into computer programming) diffs view, but the basic idea is this: (1) use digital tools to visibly mark what’s changed in your writing from one moment to another; (2) add a note that says what that change is meant to accomplish, or where it gets you; (3) reread the notes later on.

Visibly Marked Changes

Before we can talk about what you’ll learn in studying your own version histories, I want to make sure we’re all on the same page about what I’m describing, and why I find these histories so interesting. Example 1 shows a simple example of a diff, a comparison between two adjacent versions of this document. In this case, I generated it with Google Docs, using the File menu to select See Version History. But there are lots of tools you could use; pretty much any word processor these days can compare files, and most can compare versions within the same file. Leaving tool choice aside for now, let’s look at the diff together. You should recognize the context: the sentence is taken from the second paragraph above.

Example 1: Substitution at the level of words

And studies have shown that expert writers revise on those large scales more than beginners do, so learning to think big is part of how

youwe growyour expertise asawriters.

Not earth-shattering, I know; just a slight shift in wording, from you to we, from your to our. But a change doesn’t have to be massive to be meaningful. What I meant to accomplish with the change in pronouns was to change my sense of relationship to you as a reader: by including myself in the group that’s growing, I signal that I’m still learning, too—including by writing this essay and reflecting on my version history. That’s why I’m drawing on examples from this piece, so you can see how I’m learning, and what it gets me. True, I’m not exactly a novice, either: I’ve been publishing and teaching writers for almost two decades; I do think about large-scale changes and restructuring. But as this example shows, thinking about the large scales doesn’t mean you stop fiddling with sentences and words as you get more experience.

It might, though, mean you think more about how the small and the large are related, and that’s one of the big things studying your version history can help you do. For example, when I think about my reason for that small change above, you to we, it raises a question that applies to the essay as a whole: what is my relationship with readers? And what follows if I’m not separating myself from the lessons I’m trying to impart? For one thing, my examples might shift from things other people have written about to the things I have found concretely helpful, things that don’t depend on already having a large revision repertoire. It might mean, in fact, spending more time with the word-level edits we all make, and demonstrating how they can themselves lead to high-level rethinking. And so, here we are: all six paragraphs you just read are entirely new additions. Not a bad outcome for a few small tweaks!

For the change in Example 1, the structure of the sentence stayed the same: the main move was one of substitution in place, one pronoun for another. But even within a single paragraph, structural changes are possible. Example 2 shows a diff view from an earlier draft of this essay. I’d written the paragraph in one order, then decided that the last sentence made a better lead sentence—so I switched them around.

Example 2. Reordering at the level of sentences

[…] it’s an experiment everyone can do: are your changes changing as you study writing and get more focused practice and feedback?

But it’s not always easy, in the thick of the writing or after pushing through the thicket, to remember what turns you took, or why; sometimes the new versions just replace what you’d done before, whether figuratively in your memory or literally on your hard drive.In this essay, I want to make the case for using version control technology to help track and make visible what’s changing in the course of a writing project, so you can then assess how “what changes” has changed in the course of a writing class. Because it’s not always easy, in the thick of the writing or after pushing through the thicket, to remember what turns you took, or why; sometimes the new versions just replace what you’d done before, whether figuratively in your memory or literally on your hard drive.

Reordering to highlight main ideas or improve transitions is a strategy worth knowing, if you don’t already. But there’s also another, related, change in Example 2 that might be obscured by the movement of the full sentence. Do you see it? Between the deleted version (struck through) and the inserted version (underlined), the first word of the sentence changed. In its original position, the idea that “it’s not always easy” was a contrast with what came before, a turn, and so I wrote it “but”-first; within the paragraph, though, the two ideas go together, so “but” became “because.” Thinking through the reasoning here, we can develop a two-part revision strategy: First, consider whether a position change makes sense; second, reassess transitions in light of the new position.

As I said above, the small-scale strategies you can see in these diffs are often worth trying at larger scales. So, knowing that you can reorder sentences within a paragraph, you should start to realize you can reorder whole paragraphs, too. Example 3 shows the whole original paragraph from Example 2 switching places with its neighbor:

Example 3. Reordering at the level of paragraphs

[…] to help in future writing projects, I’m more interested in what strategies they used to revise – and in expanding the strategies they have experience with.

But it’s not always easy, in the thick of the writing or after pushing through the thicket, to remember what turns you took, or why; sometimes the new versions just replace what you’d done before, whether figuratively in your memory or literally on your hard drive. In this essay, I want to make the case for using version control technology to help keep track of what’s changing in the course of a writing project, so you can then assess how “what changes” has changed in the course of a writing class.For instance, in one of the classic studies of writing process, Nancy Sommers found that beginning student writers tended to make changes at the level of word, phrase, and sentence, and that most of the word/phrase changes were substitutions that didn’t change the overall structure or meaning. Expert writers, on the other hand, tended to make more changes at larger-than-paragraph levels, like theme or section, and they did a lot more cutting and reordering. So it’s an experiment everyone can do: are your changes changing as you study writing and get more focused practice and feedback?

But it’s not always easy, in the thick of the writing or after pushing through the thicket, to remember what turns you took, or why; sometimes the new versions just replace what you’d done before, whether figuratively in your memory or literally on your hard drive. In this essay, I want to make the case for using version control technology to help keep track of what’s changing in the course of a writing project, so you can then assess how “what changes” has changed in the course of a writing class.

According to our two-part strategy from sentence reordering, after we’ve tried a new position we should reassess transitions in the new position. For sentences, “transitions” meant words or phrases (“but,” “because”); scaling up to paragraphs, transitions could be whole sentences. In fact, checking transitions after the paragraph-level reordering helped me realize the “but” was no longer working; the sentence-level reordering in Example 2 was itself a smoothing operation after the paragraph switch. This suggests another strategy: What you learn at one scale, try applying at another. Note that I don’t mean just small to large; sometimes the learning works in both directions.

Noteworthy Changes Deserve a Worthy Note

Not every diff is so straightforward as the ones shown above: see Example 4, which shows a whole tangle of revisions as I worked through how to talk about the changes in my draft.

Example 4. A more complicated diff to interpret (so maybe not one for the history books)

That’s not to say you’ll stop fiddling with sentences and words as you get more experience. I’ve written plenty over the years, but

Iin those first two paragraphs alone, Icountcan see at least seveneditsword-level changes that shifted the emphasis or clarified what I meant,.edits that feel important enough to me as a writer to name:Some wording changes are powerful.For examplechanged pronouns, including myself by changing you to we in the ; I added new? The last sentence of paragraph two used to talk about “how you grow your expertise as a writer,” until I acknowledged that I’m still growing, so I changed the pronouns to include myself.

I went from planning a list of seven edits to choosing one to focus on; I tried describing some edits as “important” in a single word, then as a whole expanded phrase, then cut both. This moment in the revision process was kind of a mess, really. Why show it to you, then? A few reasons.

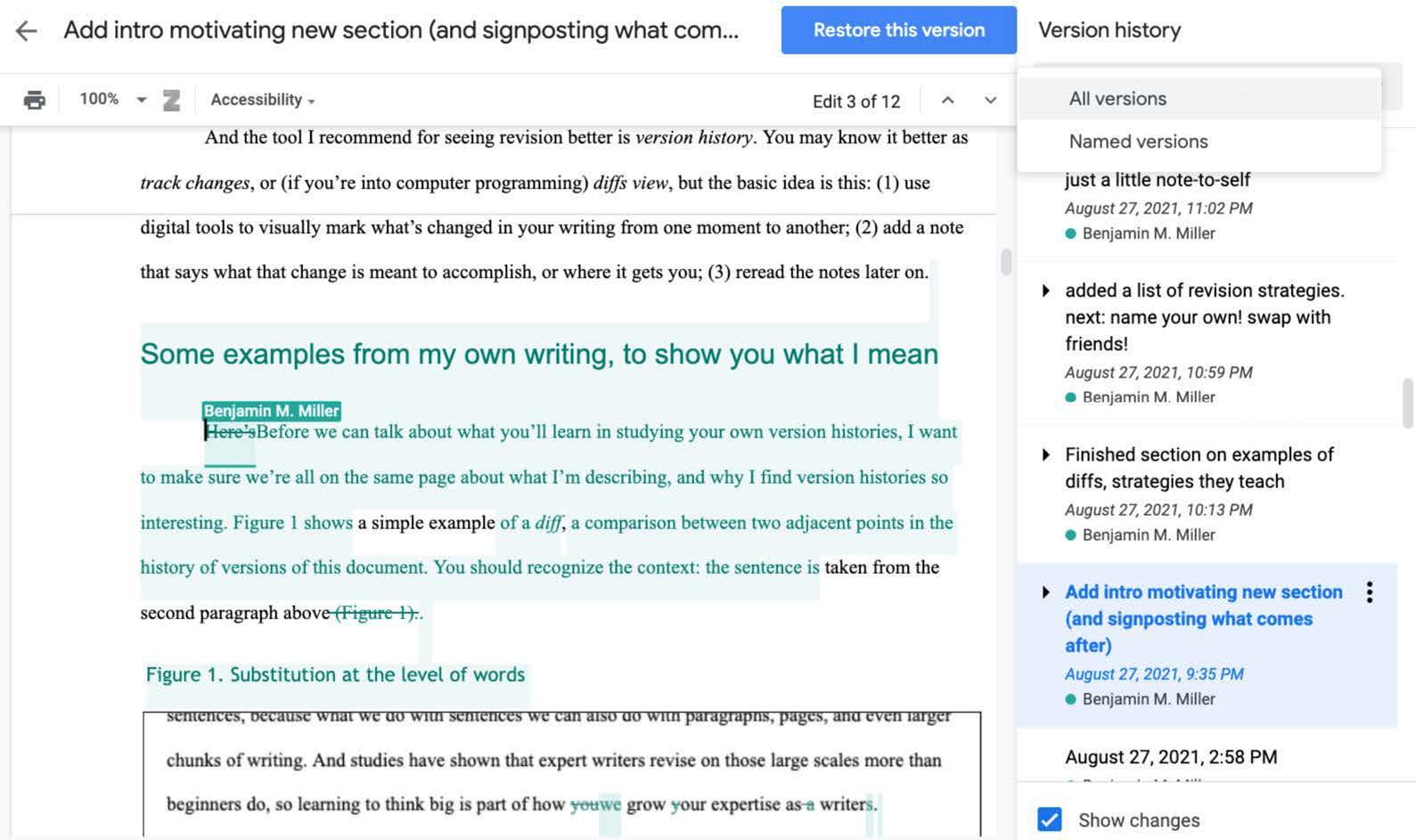

First, to make sure I’m not overstating my claim or setting you up for confusion. The truth is, not every diff is important or a source of great insight. Sometimes, the best response is to acknowledge that drafting is messy, and move on. Second, following from that truth, the moments that do feel like accomplishments are worth marking, so you can find them again later. (See Figure 1, below, where several revisions are marked with notes, and the less interesting moments in the history are marked simply as dates.)

Luckily, many writing tools with version trackers let you add “named versions” within the file’s history.[1] You can use these names to say where you are relative to some point in the process, as in “first draft” or “500 words to go”; or, even better, you can use the notes to briefly describe what’s changing, and why. A note like “first draft” doesn’t tell you, if you look back at it later, how far you’d gotten by the first draft. By contrast, a note like “reorder Sommers quote from third page to first” or “finished section on barracudas” tells you what you’ve actually done. A glance back through a series of such notes when the essay is complete can help you call to mind all the highlights of your process and reflect on what you learned—or what you want to ask for feedback on.

Google Docs version of this chapter. Even the limited space of the annotation

allows various kinds of notes: descriptions of what’s changed (“Finished section

on examples of diffs”), status updates (“Just a little note to self”), plans for future

working sessions (“next: name your own! swap with friends!”), etc. Screenshot

shows a list of five timestamped versions of a document, with labels including text

quoted in the figure caption. An option to show only named versions is unselected.

Screenshot by author.

But even before the essay is complete, these notes can be powerful. Pausing to describe what you were just working on—even pausing to decide whether to describe what you were working on—opens up a space for reflection. Version notes invite you to think actively about how you’re writing, whether to save a move you just made for future reference or to compare your present writing situation to others you’ve been in before. And that kind of metacognition, or thinking about your thinking, has been found to be important in developing expertise (How People Learn 50, 18).

What’s more, if your writing is interrupted (life happens), version notes can be a place to lay down tracks for yourself to return to. Scrolling through just the noteworthy moments when you get back, you might well recover the momentum you had when you left off, allowing you to resume midstream rather than just read the whole draft from the top. Paul Ford, writing in the New York Times about open source software, had a memorable take on this kind of process recap. He wrote, “I read the change logs, and I think: humans can do things.” If you find yourself in the grip of writer’s block, version notes can offer a reminder: you, a writer, can do things.

Looking Back to Look Forward

I’m taking the phrase “revision strategies” from one of the classic studies of writing processes, by Nancy Sommers. By comparing early and late drafts in two groups of writers, she identified four recurring “operations”—addition, subtraction, substitution, and reordering—taking place at four different “levels” of text: word, phrase, sentence, and “theme (the extended statement of one idea)” (Sommers 380). Most interestingly for practical purposes, she found a difference between the two groups based on their experience level. Beginning student writers tended to make changes on the scale of words, phrases, and sentences, and most of the word/phrase changes were substitutions: they didn’t change the overall structure or even meaning, since a lot of the substituted words were synonyms. Professional adult writers made small changes, too, but also tended to go beyond—they made more changes at larger-than-paragraph levels, like theme or section, and they did a lot more cutting and reordering.

Their revision goals were different, too: the student writers in Sommers’s study mostly wanted to “clean up” their early drafts (381), while the experienced writers talked about taking their drafts apart to find the heart of the argument (383-4)—in a sense, using revision to “rough up” the earlier draft and make something better from the pieces. Sommers’s experiment was a long time ago, but it’s an experiment you can repeat even more easily now, with your own writing: When you have to revisit a first draft, do you look for ways to “clean it up”? Or do you ask yourself what else, what next idea or better explanation, the draft helps you figure out?

ing, whether to save a move you just made for future reference or to compare your present writing situation to others you’ve been in before. And that kind of metacognition, or thinking about your thinking, has been found to be important in developing expertise (How People Learn 50, 18).

What’s more, if your writing is interrupted (life happens), version notes can be a place to lay down tracks for yourself to return to. Scrolling through just the noteworthy moments when you get back, you might well recover the momentum you had when you left off, allowing you to resume midstream rather than just read the whole draft from the top. Paul Ford, writing in the New York Times about open source software, had a memorable take on this kind of process recap. He wrote, “I read the change logs, and I think: humans can do things.” If you find yourself in the grip of writer’s block, version notes can offer a reminder: you, a writer, can do things.

Looking Back to Look Forward

I’m taking the phrase “revision strategies” from one of the classic studies of writing processes, by Nancy Sommers. By comparing early and late drafts in two groups of writers, she identified four recurring “operations”—addition, subtraction, substitution, and reordering—taking place at four different “levels” of text: word, phrase, sentence, and “theme (the extended statement of one idea)” (Sommers 380). Most interestingly for practical purposes, she found a difference between the two groups based on their experience level. Beginning student writers tended to make changes on the scale of words, phrases, and sentences, and most of the word/phrase changes were substitutions: they didn’t change the overall structure or even meaning, since a lot of the substituted words were synonyms. Professional adult writers made small changes, too, but also tended to go beyond—they made more changes at larger-than-paragraph levels, like theme or section, and they did a lot more cutting and reordering.

Their revision goals were different, too: the student writers in Sommers’s study mostly wanted to “clean up” their early drafts (381), while the experienced writers talked about taking their drafts apart to find the heart of the argument (383-4)—in a sense, using revision to “rough up” the earlier draft and make something better from the pieces. Sommers’s experiment was a long time ago, but it’s an experiment you can repeat even more easily now, with your own writing: When you have to revisit a first draft, do you look for ways to “clean it up”? Or do you ask yourself what else, what next idea or better explanation, the draft helps you figure out?

What do you think your revision history would have to say about it? It’s worth asking, because what we think we’re doing and what the evidence shows aren’t always the same. In 2018, Heather Lindenman and colleagues published a study comparing students’ drafts with reflective memos they’d written about them. They found that many students claimed to have learned new revision skills in their first-year writing courses, but those revision moves weren’t actually there when the researchers looked at the diffs. As the authors put it, “students articulated improved writing knowledge in their memos—they talked the talk—but they did not enact it in their revisions—they did not walk the walk” (589). So if you feel like you’ve realized something new this semester about how to improve your writing, it’s worth checking to see if it’s actually showing up in your latest drafts. What you expect is changing in your writing, or what you hope is changing, may or may not be visible there.

It’s not always easy, in the thick of the writing, to remember what turns you took, or why; sometimes the new versions just replace what you’d done before, whether figuratively in your memory or literally on your hard drive. Using version history can help you keep track of what you’ve done throughout the course of a writing project, so you can then assess how your strategies have changed—and where they might be useful again in the future.

So before you write a final reflection, on either that piece of writing or a whole course, you’d do well to grab some evidence from your revision history. Or, if you find it’s not there yet, you can start making some new history now.

The More Strategies, the Merrier

To find more revision strategies, you may only have to start looking at drafts where something really clicked—where you know your revisions really improved the final product. But to get the most out of it, work with a group. If you share what you find among peers, classmates, or other writing partners, the chances increase that everyone will pick up something new.

In the interest of such sharing, here are a few moves I’ve noticed recurring in my diffs:

- Thickening. Add a new sentence between two existing ones, e.g. to add more detail to an otherwise general statement. Especially useful around quotations that need more context.

- Prying open. The scaled-up, paragraph-level version of thickening: add a whole new paragraph between existing paragraphs, e.g. to insert a more concrete example of an abstract idea, or to acknowledge and respond to some possible misreading. Also works with sections (see Example 6).

- Regrouping. Sometimes, instead of new material, all you need is a change in punctuation. Adding a period (or a paragraph break) can sometimes let your readers catch their breath and fully understand one thought before you ask them to move on (see Example 5). Section headings can do the same at a larger scale (see Example 6). Conversely, substituting a semicolon for a period can emphasize how closely two ideas are related.

- Reframing. Add new material at the beginning of the draft (or paragraph, or section) with the goal of helping readers see how the existing material fits into a larger conversation; see Example 7, below. Note that this could also be considered a scaled-up version of a traditional sentence-level strategy like adding transitions.

- Removing the scaffolding. Kind of the opposite of reframing: delete preparatory passages that aren’t part of the actual building / idea, even though you couldn’t have built it without them.

- Making it explicit. Add new material at the end of a sentence, paragraph, or section to explain the significance or consequence of what you just said. Say outright what you thought was implied the first time.

- Fine-tuning. Substitute individual words to adjust their overtones, so they better match your intended root meaning. (For example, I wanted “overtones” in that sentence rather than “associations,” because “overtones” is associated with music and reinforces the musical aspect of “tuning.”)

To find these, as I said, I went through my version history and tried to (a) describe the changes I saw, and (b) explain what I hoped each change would accomplish. You can do the same, especially if you already took notes as you went along to mark the revisions of which you’re the most proud.

Example 5. Regrouping at the sentence level (replacing colon with period)

In this essay, I want to help you see revision better:. I want to help you think through what you do with sentences, because what we do with sentences we can also do with paragraphs, pages, and even larger chunks of writing.

Example 6. Regrouping to carve out an extra section within an existing one

The more strategies, the merrierWhere I’m coming from, and where you’re goingI’m taking the phrase “revision strategies” from one of the classic studies of writing process, by Nancy Sommers. By comparing early and late drafts in two groups of writers, she found that beginning student writers tended to make changes at the level of word, phrase, and sentence, and that most of the word/phrase changes were substitutions: they didn’t change the overall structure or meaning. Experienced adult writers made those changes, too, but also tended to go beyond—they made more changes at larger-than-paragraph levels, like theme or section, and they did a lot more cutting and reordering.

The more strategies, the merrier

Sommers’ original article makes from some great reading, despite its kind of boring title […]

From Discovery to Planning

So far, my advice has mostly been retrospective: I’m asking you to look back at the revisions you’ve already made, and glean strategies from them. That’s not a bad place to start, but the bigger goal is to improve your writing by expanding the ways you know how to improve your writing. This raises an important question: How will you know when to apply one kind of strategy over another—when to add more in the middle or the beginning, when to reorder or regroup?

Example 7. Reframing by adding at the start of a section

Strategy Search Suggestions

So far, my advice has been mostly retrospective: I’m asking you to look back at the revision you’ve already made, and glean strategies from them. That’s not a bad place to start, but the bigger goal isn’t simply to label and catalog all these moves, but rather to use them moving forward, to improve your writing by expanding the ways you know how to improve writing. This raises an important question: How will you know when to apply one kind of strategy over another—when to add more in the middle, when to reorder or regroup? Unfortunately, there’s no hard and fast rule: it’ll usually depend on the particulars of your argument […]

Unfortunately, there’s no hard and fast set of rules: it’ll ultimately depend on the particulars of your argument or narrative when you might want to restructure, or thicken, or reframe. Sometimes the best approach is to ask friendly readers where they had questions or had to reread more than once to understand. But since reordering is often both my most challenging and most rewarding revision move, here’s what has helped me realize it might be time to try it:

- Distant callbacks. If you find yourself saying things like “As I said earlier,” it’s worth checking how much earlier it was. If readers will have to remember your point from before a whole intervening section, maybe it would make more sense to reposition the new part closer to the first part. On the other hand, maybe all you need is a regrouping: could you add new section titles to help readers anticipate the jump away from the first idea and back to it later? That might make it easier to follow your line of thought.

- Bringing it down to size, for example, with a “reverse sentence outline.” A reverse outline is one you write after a draft exists, allowing you—like Sommers’ experienced adult writers—to search that draft for the shape of an emerging argument, rather than assume the argument is already clear. By outlining in sentences, you essentially scale down the big picture into a paragraph or two: for many writers, a more familiar and manageable space in which to regroup, reorder, and recognize gaps to fill in (or extraneous chunks to cut). Once you’ve done it with the outline, the corresponding changes you can make in the piece as a whole should be easier to identify.

For regrouping, I think about needing a break. Beginnings and endings are positions of power; anything next to a pause gets extra emphasis. Conversely, long stretches without a beginning or ending—whether it’s a four-line sentence or a full-page paragraph—seem to suggest there’s nothing worth emphasizing. But that’s usually not the case! So when I see a long paragraph or sentence, I look more closely for the highlights, and I try to place a period or paragraph break alongside them.

There are troves of authors with additional advice and suggested moves to look into; I’ve found Wendy Bishop’s “Revising Out and Revising In” and E. Shelley Reid’s Solving Writing Problems to be particularly helpful. Whatever move you choose, if you take a note as you’re trying it, you’ll be able to come back later and assess how successful it was for your draft. And seeing it in the context of your other named versions will help you consider whether it might work as well, or better, at another point in your process or on another level of scale.

A Parade of Small Rewards

Looking back and looking forward are all well and good, but above all it’s the mid-process reflection that keeps me coming back to diffs. Recording what’s changing helps us realize that there is actual progress happening, even when it might not look like it. As someone who has struggled with writer’s block and anxiety for as long as I can remember, many of my first drafts don’t look like much of anything, often for a long time. But a look through my diffs shows the progress that word counts alone would leave invisible: the hundreds of words written, then erased; the paragraphs of ideas in a particular order that turned out to be incompatible with another structure, and so had to be cut. In naming each revision, even when the revision move is subtraction, we get to pause and celebrate the writing that was there.

When do you usually celebrate your writing? When the essay is complete? When a grade comes back (depending on the grade)? When you don’t have to think about it any more? By acknowledging the hard work and successes of mid-draft changes, version history reminds us that the journey itself is studded with small victories.

Works Cited

Bishop, Wendy. “Revising Out and Revising In.” Acts of Revision: A Guide for Writers, edited by Wendy Bishop, Boynton/Cook Heinemann, 2004, pp. 13-27.

Ford, Paul. “Letter of Recommendation: Bug Fixes.” The New York Times, 11 June 2019. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/11/magazine/ letter-of-recommendation-bug-fixes-git.html.

How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition. 2nd ed., National Academy Press, 2000. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/9853/ how-people-learn-brain-mind-experience-and-school-expanded-edition.

Lindenman, Heather, Martin Camper, Lindsay Dunne Jacoby, and Jessica Enoch. “Revision and Reflection: A Study of (Dis)Connections between Writing Knowledge and Writing Practice.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 69, no. 4, June 2018, pp. 581-611.

Sommers, Nancy. “Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 31, no. 4, Dec. 1980, pp. 378-88.

Attributions

This chapter, “What’s the Diff? Version History and Revision Reflections,” by Benjamin Miller was published in Writing Spaces and is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.

- In LibreOffice, you can find the option to name a save under File > Versions… > Save New Version; in Google Docs, timestamps saved automatically under File > Version History can be renamed (though only 40 per document). One version tracker popular among programmers and technical writers, called git, tracks only these named versions, which it calls “commits.” I kind of love the energy of that: it’s like, “Okay, I know you’ve saved this file, but are you ready to commit to it? Is this an official version you’d want to look at again later?” ↵